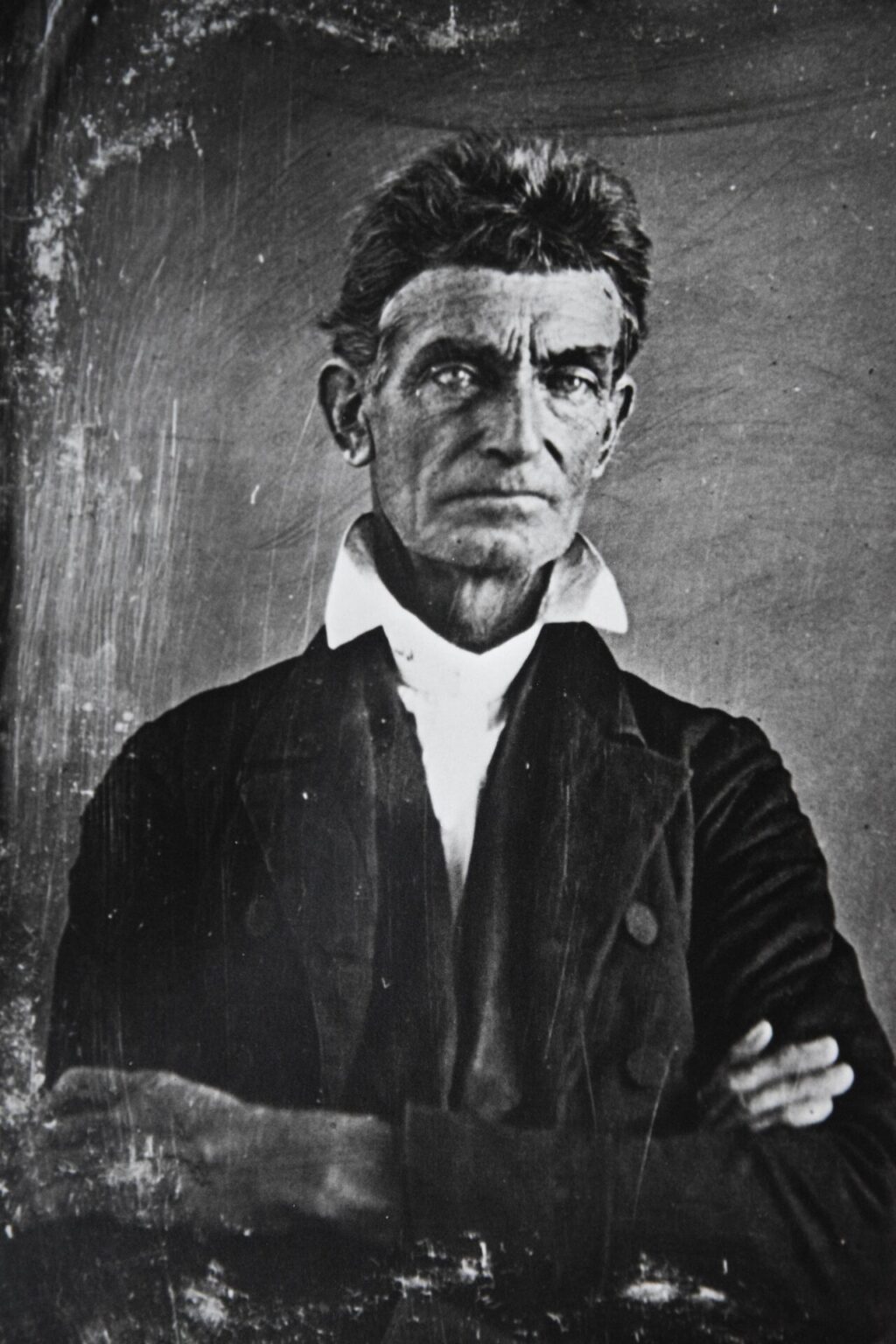

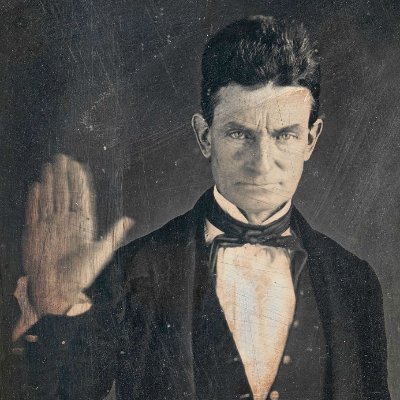

In June of 1859, John Brown secretly arrived in Franklin County, Pennsylvania. He was already a polarizing national figure, wanted for multiple murders in Kansas. To disguise himself, Brown grew a long white beard and used the alias “Dr. Isaac Smith”.

Pretending to be Smith, Brown registered at a Chambersburg boardinghouse on King Street. The property was owned by the widow Mary Ritner, daughter-in-law of Joseph Ritner, a former abolitionist Pennsylvania Governor.

John Brown was a noteworthy abolitionist himself, and had launched his own violent brand of solutions to America’s escalating slavery controversy. In 1859, American states were still tenuously united, but Brown’s actions that autumn would prove a fiery catalyst for a disastrous tear in the union’s fabric.

At that time, a Franklin County native occupied the White House. The 15th U.S. President was James Buchanan, born near Cove Gap. After childhood, he had departed the area to pursue the law and politics in Pennsylvania’s Lancaster County. Buchanan quickly rose in Democratic Party circles, serving as a U.S. House Representative and Senator, and then later was chosen as Secretary of State under President Polk. With Buchanan’s impressive resume, he appeared to be a capable leader for a tumultuous time.

But many abolitionist citizens accused the President of harboring southern sympathies and thought Buchanan sat idle when slavery’s potential expansion was debated and southern states threatened to secede. As his term neared an end in 1859, and regional tensions reached a boiling point between north and south, Buchanan abandoned any thought of re-election. He would pass on America’s explosive slavery dilemma to the next president.

John Brown’s action-based beliefs contrasted with Buchanan’s do-nothing slavery policies. Brown believed the time for decisive action had arrived and he came to Chambersburg with a clear purpose. His daring plan centered on a small river town 52 miles to the south. Brown thought Chambersburg a safe staging area for his upcoming revolution.

Franklin County was a notable stop on the Underground Railroad, a temporary haven for African Americans traveling toward freedom. While Brown sympathized with slaves escaping oppression, he didn’t participate in freeing those individuals while in Chambersburg. John Brown had a much higher purpose: he wanted to free all American slaves.

John Brown was born in Connecticut on May 9, 1800, but moved with his family to Ohio at age five. Hudson, Ohio was a fiercely abolitionist town and Brown’s father, Owen, offered their home as a safe house to runaway slaves.

When John Brown was twelve, he supposedly witnessed a slave being beaten and Brown then decided to devote future energies to that oppressed race. As a young adult, Brown married and opened a successful tannery. During this time, John Brown developed into a devout Christian and memorized the bible. His concern for the awful plight of enslaved black Americans never wavered.

Brown moved to Pennsylvania in 1825. He opened a new tannery but also followed in his father’s footsteps, operating his own safe house on the Underground Railroad. During ten years there, John Brown’s farm hosted an estimated 2,500 slaves on their journey toward safety in Canada.

After his first wife died, Brown married again in 1833. He would eventually father 20 children. Many of Brown’s sons would follow their father into the abolitionist movement, just like John Brown gained inspiration from his father.

Initially successful as a businessman, Brown suffered great financial losses during the panic of 1837. He returned to Ohio; then began a series of sporadic moves to Massachusetts and New York. John Brown floundered. He searched for a way to get out of debt, but eventually declared bankruptcy in 1842. Three of Brown’s children died of dysentery the next year. During this trying time, John Brown’s anti-slavery sentiments and religious convictions gathered fatal momentum.

Five of Brown’s remaining sons moved to the Kansas Territory in 1855, and John Brown joined them. As a family, they hoped to unite with abolitionist settlers who intended to bring Kansas into the union as a free state. The territory’s slavery issue became hostile when pro-slavery forces destroyed two abolitionist newspapers. John Brown was outraged and thought his free-state comrades cowardly for not fighting back with greater force.

On the evening of May 24, 1856, a group of armed men, led by John Brown and his sons, took pro-slave Kansas settlers from their homes and killed five with swords. Brown described these victims as “professional slave hunters and militant pro-slavery settlers”. The resulting retaliatory raids and unchecked violence resulted in many more deaths, inspiring the infamous term: “Bleeding Kansas”.

Two of Brown’s sons were captured and charged with murder in Kansas, another son was killed in a later battle. But John Brown escaped. With federal warrants on his head, he eventually traveled east to plan and execute a history-changing scheme.

During his 1859 time in Chambersburg, Brown made connections and gathered munitions. John Brown’s ambitious plan: to seize the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, arm local slaves with stolen weapons, and launch a slave insurrection. It was estimated that 100,000 muskets and rifles were stored at the Harpers Ferry armory.

Always a religious man, Brown found time while in the Chambersburg area to teach Sunday school at Mont Alto’s Emmanuel Chapel. He visited Greencastle’s Union Hotel, and frequented a local railroad depot where he shipped and received weapons- some munitions came from as far away as Iowa. Brown’s Harpers Ferry operation was funded by a shadowy group of backers labeled the “Secret Six”.

Late in the summer, Brown held a historical secret meeting near a Chambersburg quarry. America’s most renowned African American and famous abolitionist was Frederick Douglass. Brown met Douglass and told him about his secret plan, trying to enlist Douglass’s support. But Douglass deferred, later calling Brown’s raid “sheer madness”. Douglass left Chambersburg after delivering a memorable speech, and distanced himself from Brown.

As the day of his attack drew near, Brown moved his covert operation closer to Harpers Ferry, to the Kennedy Farm in Washington County, Maryland. While there, the conspirators pretended to research local mining opportunities.

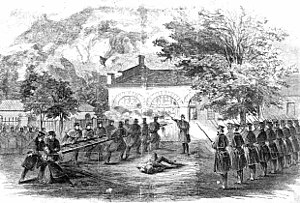

On October 16, 1859, Brown and 21 supporters attacked the Harpers Ferry arsenal. At first, the group found success overwhelming guards (seven sentinels were killed), taking hostages, and securing control of the facility. But the tide turned when local militia and angry citizens fought back.

When U.S. Marines arrived, Brown and his men barricaded themselves in a small brick building, refusing to surrender. First in command for the federal government’s forces: Colonel Robert E. Lee. The Marines stormed the building, and in the ensuing melee, Brown’s sons Watson and Oliver were killed. Outnumbered, Brown and his remaining men were captured. His meticulously planned revolution had failed.

Brown was charged with murder, treason, and inciting a slave insurrection. With swift justice he was convicted and sentenced, along with nine of his followers. On December 2nd, as the first American sentenced to death for treason, Brown was unapologetic when led to the gallows. He saw himself like Moses, leading followers to a promised land. Before his execution he said: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood”. Later, always nomadic during his life, Brown’s mortal remains were buried in New York State.

Brown’s ominous prediction was sadly prophetic. The Civil War erupted in 1861, and many pointed to Brown’s actions as a tipping point in already hostile north/south relations. During the war, northern soldiers marched to an inspirational tune titled “John Brown’s Body”. Juliette Ward Howe wrote Battle Hymn of the Republic, also inspired by Brown’s actions. New President Abraham Lincoln severed Harpers Ferry’s tie to Virginia by creating a new pro-union state of West Virginia.

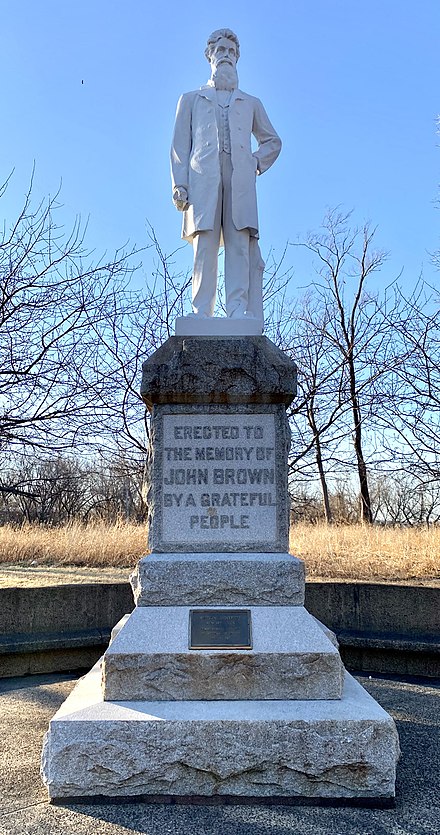

John Brown’s legacy is a complicated collage of loyalties and regional sentiments. While some considered him a heroic martyr, others saw Brown as a murderous madman. His government thought him the latter, taking his life. At the time, notable abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called Brown’s raid “well-intended, but sadly misguided”. Future historians would split their opinions about Brown’s positive or negative influence on the abolitionist movement.

Today, the Chambersburg boarding house where he planned his infamous raid is called the John Brown House. That old Ritner property has been restored with period furnishing and is open for tours sponsored by the Franklin County Historical Society. In Sharpsburg, the Kennedy Farm is a historic log farmhouse also open for visits. Both properties are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places.

In Harpers Ferry, a National Historic Park remembers the community’s significance, located at the scenic confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. The town has multiple historic sites worth exploring and memory of John Brown’s raid still lingers there.

Regardless of his final reputation, John Brown was a pivotal figure in American history. The devotion to his cause was evident in intense eyes. That passion brought him to the Cumberland Valley in 1859, a trying time when some Americans were still enslaved, and a select few were willing to fight and die to end that inhuman institution.