In the middle 1600s, when the British Crown was handing out land grants in North America, the Penn family of Pennsylvania and the Calvert family of Maryland shared a property border. That boundary supposedly ran east-west near the 40th parallel, but wording of the King’s land grants for those two territories was confusing and also based on faulty maps. This placed the two colonies geographically at odds.

For over 80 years, no one knew exactly where that border should be. By the 1730’s, violence broke out on both sides of the Pennsylvania/Maryland line, one skirmish called “Cresap’s War”. This agitation persisted into the mid-1700s until, finally, the British Crown, the Penn’s, and the Calvert’s, hired two surveyors referred by London’s Royal Observatory.

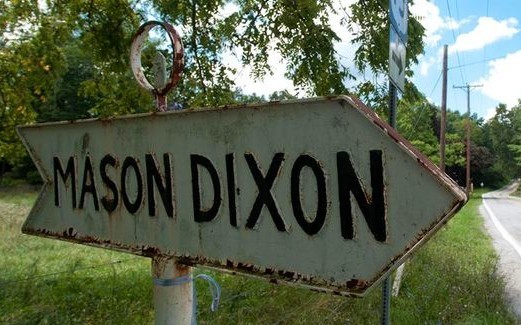

Their mission: survey the north-south line dividing Maryland and Delaware, and then demarcate the east-west line between Pennsylvania and Maryland. The two surveyor’s names: Mason and Dixon. Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, both British subjects, were not just surveyors, but astronomers and mathematicians. Aside from their mapping talents, the duo lived vastly different lives.

Charles Mason (born 1728, died 1786) came from an astronomy background, and made influential friends within his science early in his career. A family man, Mason would marry and father eight children. Before coming to America, he worked to perfect Lunar Tables, which established longitude at sea. Mason’s exacting astronomy work would be recognized with a moon crater named in his honor. When Mason later died in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin mourned.

Jeremiah Dixon (1733-1779) came from a working-class mining family. Born a Quaker, Dixon was known to push his faith’s boundaries by wearing flashy clothing (a red coat his favorite attire) and by regularly imbibing alcoholic spirits. A lifelong bachelor, Dixon practiced surveying while apparently leading a hedonistic lifestyle. After his death back in England, his story seemed destined for obscurity. But many years later, some suggest Dixon’s name inspired the term “Dixie” to commemorate the U.S. south.

In 1761, the Mason and Dixon joined forces for the first time, both assigned to measure a transit of Venus in Sumatra. The journey ended at the Cape of Good Hope instead, where the two men conducted their planetary calculations. Their partnership established, two years later they were summoned to America to settle Maryland and Pennsylvania’s persistent boundary dispute.

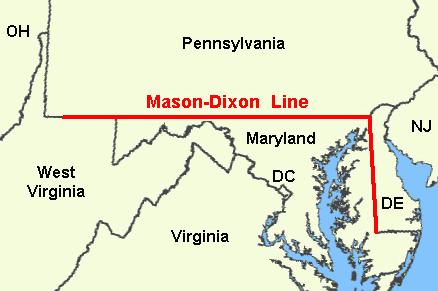

Dixon and Mason accomplished their north-south Delaware-Maryland survey work between 1763 and 1765. Then, turning their attention to the better known east-west line between Maryland and Pennsylvania, they worked there in 1765-1767, and cemented their place in history.

Mason and Dixon marked every mile along the Maryland and Pennsylvania border with limestone marker stones quarried, carved, and shipped from England. The ordinary mile-marker stones bore an “M” for Maryland on the south-facing side, and a “P” for Pennsylvania on the opposite north-facing section. Every fifth mile called for a special marker, referred to as a “crown stone,” that bore a carving of Penn’s family coat of arms on the north face and Calvert’s family crest on the south side.

The first east-west stone was set near Stricklersville, PA, on November 5, 1765. The 132nd and final stone was set near Sideling Hill on November 28, 1767. Between those points, Mason, Dixon, and their team braved wilderness which included rugged mountains, raging rivers, wild animals, and sometimes hostile natives.

Beyond Sideling Hill, the wilderness terrain was too daunting to haul heavy pre-carved markers, so the surveyors continued their work, but marked each mile with rock cairns. A later 1902 re-survey finished marking the line by placing modern concrete markers at every remaining mile.

Mason and Dixon performed their survey west from the Philadelphia area almost to the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania. The surveyors were stopped some 30 miles short of that corner due to access issues with native Iroquois, who were justifiably skeptical over British map-making efforts.

The two famous surveyors used a combination of transits and telescopes. One particular instrument, called a “Zenith Sector” was a six-foot brass telescope suspended on metal framework. At the time, it was the most accurate tool to determine latitude.

Since the 1760s, surveying technology has obviously improved. Modern GPS has retraced Charles Mason’s and Jeremiah Dixon’s handiwork, and found most stones they placed two and a half centuries ago were accurate within a few feet.

Since Franklin County, Pennsylvania and Washington County, Maryland are separated by the celebrated Mason-Dixon Line, these priceless original stones, and the rich stories associated with them, are often recalled locally.

In the aptly named town of State Line, a tale survives of an illicit distiller who not only lived in close proximity to the Mason-Dixon Line- the boundary bisected his home. Supposedly, when Pennsylvania revenuers raided his home, the frustrated lawmen found the whiskey-maker had simply moved his illegal liquor stash to the Maryland side of his house.

Mason and Dixon passed through the Cumberland Valley in September, 1766. Near modern day Pen Mar, (another community name that honors the famous two-state border), they reportedly struggled with the rugged topography and found their first marker was inaccurate by hundreds of yards. They then utilized their trusty Zenith Sector to correct their mistake. In his daily journal shortly afterward, Mason wrote a brief but dedicated entry: “Continued the line.”

The Mason-Dixon Line is arguably the most famous surveyor’s line ever drawn. But the east-west section is not a true straight line, but is a polygonal chain instead; a series of adjoining line segments along a path of coordinates 39/43/15 north and 39/43/23 north. In total, the PA/MD portion of the Mason-Dixon Line runs for 233 miles.

Dixon and Mason would likely be surprised by their lasting historical legacy. When the survey was finally completed, the official report didn’t promote either man. Within twenty years of their historic project’s completion, both Dixon and Mason died.

But in 1820, their surveying exploits were revived. The historic Missouri Compromise was an attempt to stop slavery’s spread into new northern states. “Mason and Dixon’s Line” was mentioned prominently during that congressional negotiation and passage into law. From that point forward, their two monikers would be attached to that PA/MD dividing line and its significance would grow.

Earlier in 1780, Pennsylvania initiated their eventual abolition of slavery. Shortly afterward, that awful institution only existed south of the Mason-Dixon Line. With that fact, a new invisible boundary separated vastly different cultures in north and south. The Mason-Dixon Line became a social and political divider that separated enslaved and free citizens. During the Underground Railroad era and the American Civil War, attention paid to this famous map demarcation increased dramatically.

In subsequent years, the Mason-Dixon Line would thankfully signify less drama between races and societies, but would remain culturally significant. Today, the two names attached to this artificial boundary have staying power in popular American culture.

Of the 132 stones placed by Mason and Dixon in the 1760s, surprisingly most are still intact where originally placed. Some others have been stolen, buried due to farming, moved for road building, or plain lost. As civilization eventually reached that long-ago frontier, roads expanded and villages grew, so many decades later these surviving stones stand virtually unnoticed, except by someone seeking them.

For the curious, a modern-day scavenger hunt reveals remaining local Mason-Dixon Line mile-markers. Some are easily visible from public roads, but most stones actually sit on private land. As Mason and Dixon likely did in their time, respect for landowner’s property rights is always the proper way to explore.

These ancient Mason-Dixon sentinels still mark a geographic division between two states, offering a fascinating snapshot of local history. They rekindle memories of a time when two men, utilizing a clever combination of astronomy, mathematics, and surveying, placed stone monuments exactly a mile apart on America’s frontier landscape.