The story of Hagerstown’s architectural legacy begins with founder Jonathan Hager. The German immigrant came to America in 1736, and three years later, Hager purchased 200 Maryland acres near a bubbling spring. There, he built a traditional limestone home. As a community formed around it, he named the settlement Elizabethtown to honor his departed wife. Eventually, the growing city officially became known as Hagerstown in 1814.

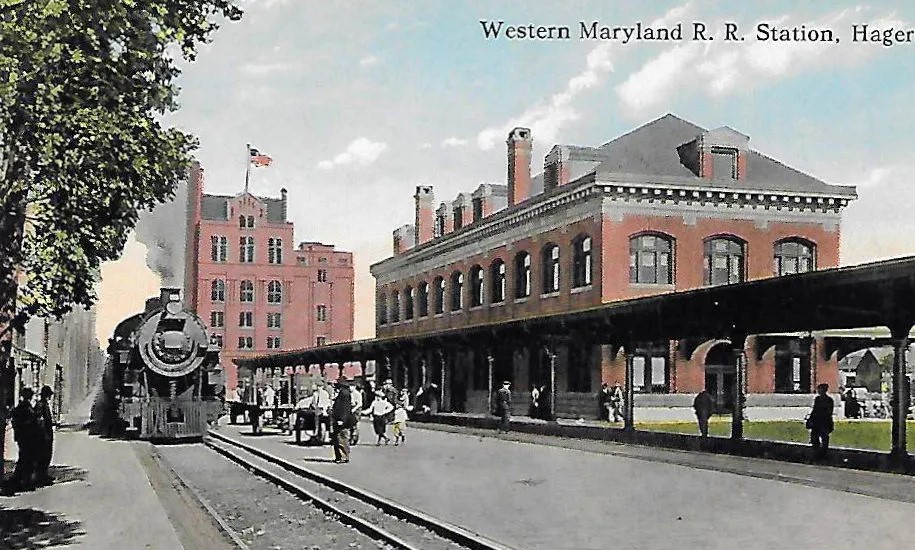

Due to Hager’s non-stop boosterism, his community was eventually named the seat of the newly created Washington County. Hagerstown later grew into a vital center for Maryland transportation and industry. The town was along the National Road, an early western gateway. Then, the railroads arrived. Hagerstown became a major crossroad rail community, earning the nickname “Hub City.” Prospering railyards linked the town and its industries to northeastern cities and Atlantic ports.

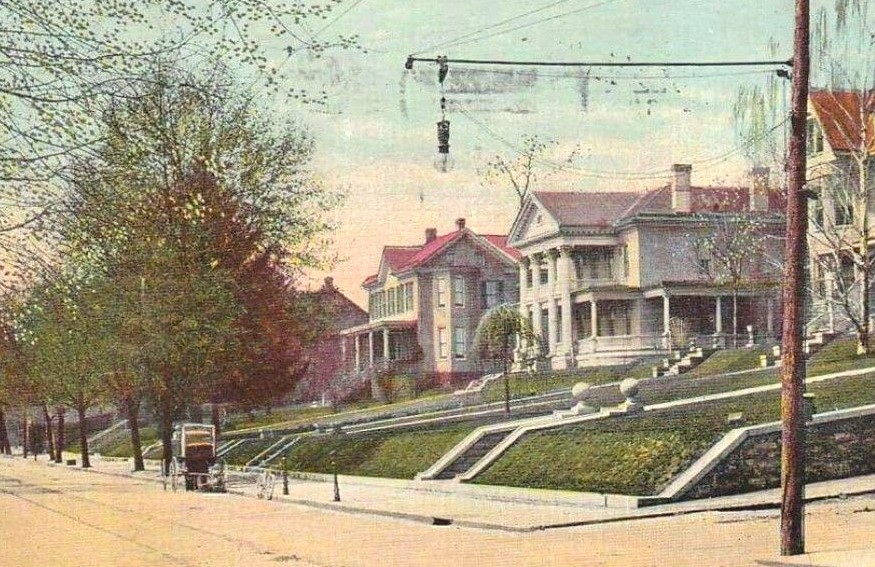

During its boom years from 1880 to 1930, Hagerstown architects and contractors built a large stock of homes to shelter its entrepreneurs and house a growing citizenry. Various neighborhoods sprung up, some sprinkled with lavish dwellings resting on hills and framed by sweeping lawns. On nearby streets, modest single and multi-family homes catered to a middle-class lifestyle.

A variety of business structures also appeared during this period, along with county government and civic buildings that occupied downtown lots. Many of these structures remain today and are honored as National Register Historic Properties. Other buildings are lovingly preserved, protecting their distinctive histories. Today, Washington County has more than 100 historic properties on the national registry, but the number of noteworthy buildings in today’s Hagerstown is likely five times that count.

Hagerstown is well-known for its charming historic districts, areas where homes exhibit the art of fine living. North of downtown, the Oak Hill neighborhood was laid out in 1909 by Clara Hamilton, wife of former Maryland Gov. William Hamilton. This area is appreciated today for its Colonial and Georgian Revival designs, with additional examples of Tudor, Spanish and Queen Anne-style homes. Many of these residences sit on large lots with generous setbacks among tree-lined and curved streets.

Nearby, the adjoining Potomac-Broadway District developed during the 1870-1930 period, and it also displays a variety of architectural styles. Among the Gothic, American Foursquare, Second Empire, plus other designs, are regal mansions, single-family homes, urban townhouses and duplexes. The west side of the 400 N. Potomac block is renowned for majestic homes built by Hagerstown’s early business pioneers.

To the south, S. Prospect Street symbolizes Hagerstown’s earlier prosperity. With 50 well-kept structures situated on a hillcrest, this area originated around 1830. Although many original structures were repurposed, the street retains the charm of an early 1900s period, with ample housing styles, including Classic Revival, Italianate and Neoclassical structures. With brick sidewalks and fascinating architecture, these few blocks of S. Prospect Street offer a pleasurable spot for a leisurely Hagerstown stroll.

Prospect Street leads toward City Park, where another unique housing district originated. Using reclaimed land once used by light industry, the area was developed for upper-middle-class families near a lovely 105-acre park and civic center.

This area with Victorian-era residences is a short walk from a scenic lake and a Beaux-Arts classical structure that hosts the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts. This cultural institution opened in 1931 within Hagerstown City Park. Enjoyed outside the museum are meandering paths, a stucco-framed bandshell and rustic stone walls in a natural landscape.

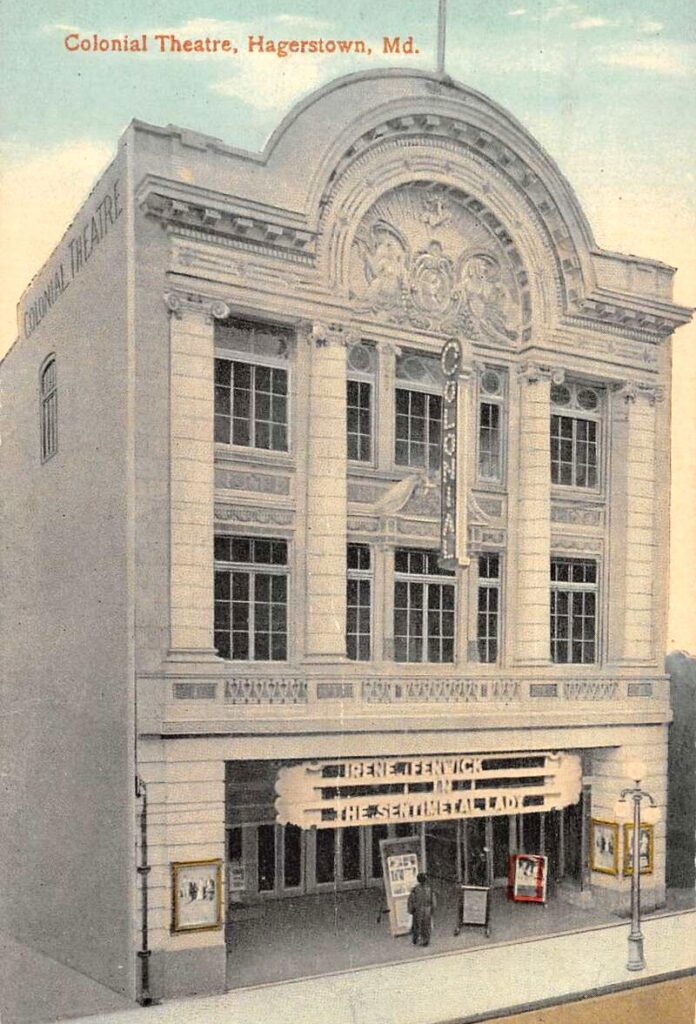

Potomac Street is Hagerstown’s main thoroughfare. Traveling north to south, it leads through a vibrant downtown and into the town’s square. Several historic buildings on the national register reside nearby, and two are famous as entertainment spaces. One theater echoes past performances, while the second venue still wows 2024 audiences.

The Colonial Theatre at 12-14 S. Potomac Street exhibits a Baroque-influenced façade with elaborate ornamentation. The upper levels have glazed white blocks with decorative gold detailing, within a Palladian window design framed by ionic pilasters. The theater last showed films in 1973, but the building’s exterior facade still performs a free show daily.

The Colonial’s playful façade reflect onto the large windows of the Maryland Theatre across the street. This venue opened on May 10, 1915. Opening-day visitors enjoyed a grand orchestra-themed show with ticket prices from 10 to 35 cents. Like its Colonial Theatre neighbor, Hagerstown’s Harry Yessler was the architect responsible for the Maryland Theatre’s design, and he developed other famous venues such as New York’s Madison Square Garden.

A fire nearly destroyed the Maryland Theatre in 1974. Then, it fell into disrepair and was scheduled for demolition to harvest its 1 million bricks. Thankfully, a Hagerstown businessman saved the building. A 2019 renovation, which added a new streetside façade, gave new luster to this theater. As home to the Maryland Symphony Orchestra, the building is a sparkling jewel in the necklace of downtown Hagerstown architecture.

Next to the theater is Maryland’s oldest working firehouse, the First Hagerstown Hose Company at 31 S. Potomac St. This large Italianate building was constructed in 1881 and still shelters two engines, and it also hosts the Museum of Firefighting History.

North on Potomac, the old Junior Firehouse #3 is being renovated by a private owner as a future event space. The ongoing restoration of the 1850s building earned recognition for recreating historically accurate paint colors on its iconic bell tower, a signature architectural element of Hagerstown’s skyline.

At another old firehouse, seen at 21 W. Franklin St., the MSB Architecture firm repurposed the former two-bay Pioneer Hook & Ladder Company as an office but smartly kept the interior fire pole onsite. Daring employees slide down that brass shaft like old-time firemen.

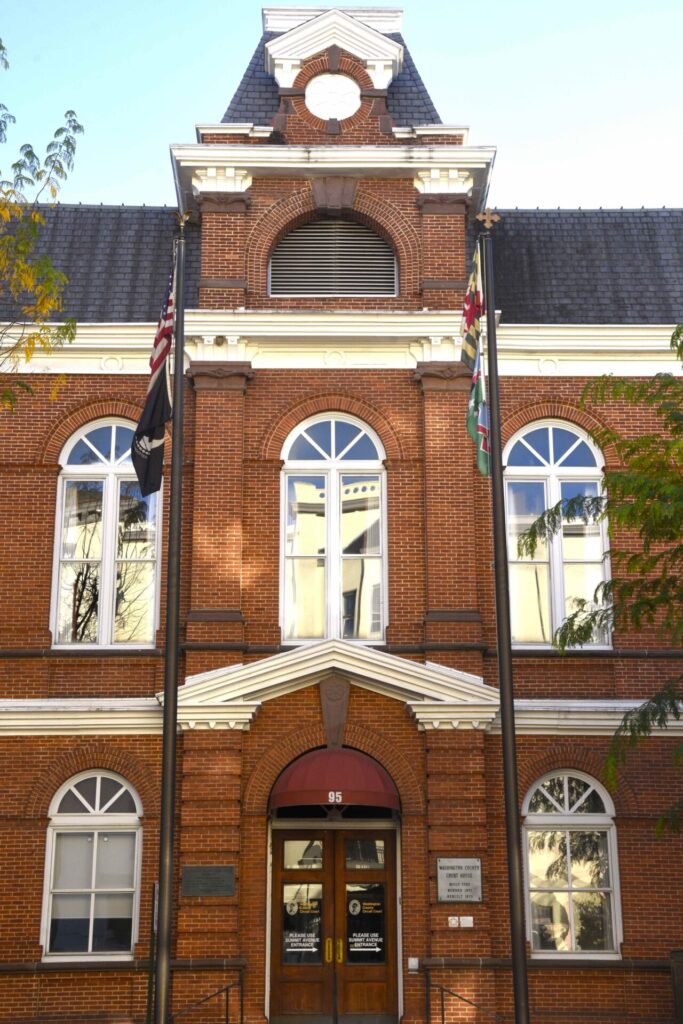

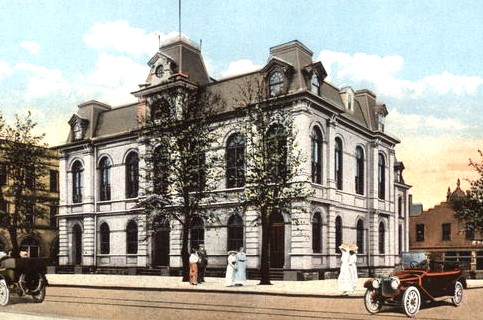

Hagerstown’s first county courthouse was on the square, but the current Washington County Courthouse sits a block west at 95 W. Washington St. This 1872 red-brick Second Empire structure stands two stories tall, with a central tower over the entrance.

This existing civic building rests on the foundation of a previous courthouse, which burned in 1871. Tragedy struck again during the second construction when a remaining wall from the scorched shell fell and killed three workmen. The father of one of those unfortunate victims also was killed when the prior courthouse burst into flames only months before.

Near the courthouse at 135 W. Washington St., the Price-Miller House is a fine example of Federal-style architecture. Once home to a prominent attorney and later a doctor, the 1825 building is now the headquarters for the Washington County Historical Society. The home retains its ornate interior with an original floating staircase that leads upward showing a graceful curve.

Along this section of Washington Street, curious eyes can spy unique architectural details that decorate commercial buildings. An ‘H’ marks the spot of one building’s ornamental cornice. During its economic heyday, Hagerstown was a manufacturing hub too, with the famous (now closed) Moller Pipe Organ Company employing many city workers, in addition to several Hagerstown furniture makers.

Railroads were the county’s largest employers for half a century. Some elements of Hagerstown’s Hub City railroad legacy have vanished — the railroad demolished the massive roundhouse complex in 1999. However, the Hagerstown Roundhouse Museum (300 S. Burhans Blvd.) still interprets the romantic history of powerful locomotives that propelled goods and passengers in Western Maryland’s bygone transportation era.

Also on Burhan’s Boulevard, a commanding relic of this historic rail era is the old Western Maryland Railway Station. This 1913 commercial style structure served as a passenger terminal until 1957. Today, this building is repurposed as a headquarters for Hagerstown’s Police Department, but its past railway function is evident by its classic early 20th-century design.

Hagerstown boasts several historic churches along Potomac Street. Near the Randolph Avenue intersection, builders placed a 1909 cornerstone for Trinity Lutheran Church. The church’s granite has weathered to a handsome hue, and gargoyles guard the bell tower at each top corner.

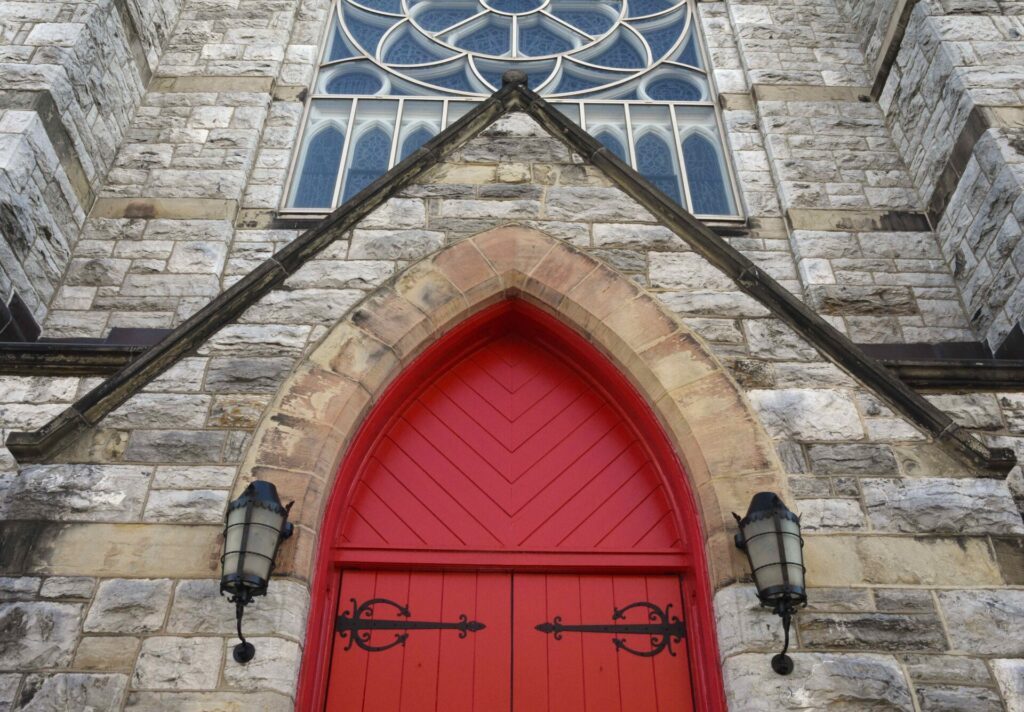

Nearby, the John Wesley United Methodist Church (Formerly St. Paul’s Church) also attracts attention. The 1885-built structure displays a vibrant red entry door and distinctive stonework. Inside, the sanctuary’s stained glass windows are “stunning”, according to current Pastor Doug Hoffman.

Only a few steps away, the Zion Reformed Church portrays the story of longtime worship, and is a link to a famous general and a tragic accident that claimed Hagerstown’s founding father’s life. Zion is also the oldest continuously used church in modern Washington County.

During the Civil War, Zion served as a temporary lookout post for Union General George Armstrong Custer and his troops. Local lore says Confederate sharpshooters fired at Custer in the tower, pinging the bells, but he survived. Custer eventually died during his infamous 1876 “last stand” at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Previously, when this historic church was under construction, Jonathan Hager helped build the sanctuary. He had generously donated two building lots for the new house of worship. On Dec. 5, 1775, during the installation of a heavy ceiling beam, that massive column slipped and fell, fatally wounding Hager. A mourning family buried him only steps away in the church’s quiet cemetery. Hager’s charitable deeds and faithful leadership are still remembered at Zion.

Sitting quietly near the City Park lake, the original Hager House symbolizes Hagerstown’s longtime achievement as a protector of precious architecture. The city took over the property in 1944 and spent 10 years restoring the stone structure. After opening to the public in 1962, a modern tour reveals a typical German-style home from the mid-1700s period with a large cooking fireplace inside and a banked structure outside, set on a basement situated over a stream-fed spring.

Hager was a fur trader, miller and farmer. He encouraged the area’s growth by opening his home as a trading post. Originally one story, the next owner built a second-floor addition to the rustic homestead. This setting, where Hagerstown was born, is still tranquil today.

Hagerstown and surrounding Washington County exhibit many more specimens of distinctive architecture and successful historic preservation stories. But downtown is a logical starting point for exploration. Various Hub City structures teach how people once lived, worked, worshipped and played as Hagerstown developed into its modern identity.

Many local residents and workers still enjoy these buildings every day, in old and new formats. They appreciate the community’s architectural design, uniqueness and longevity. Jonathan Hager would surely be proud of the city he inspired.