As Pennsylvania prepared to vote in the 1924 presidential election, specific political topics and pressing economic concerns were prominent in Waynesboro residents’ minds as they entered voting booths. Some of those voting factors reflected American life during the “Roaring Twenties,” while other 1924 ideals, such as judging conservative versus progressive agendas, were similar to issues debated during the modern 2024 national election.

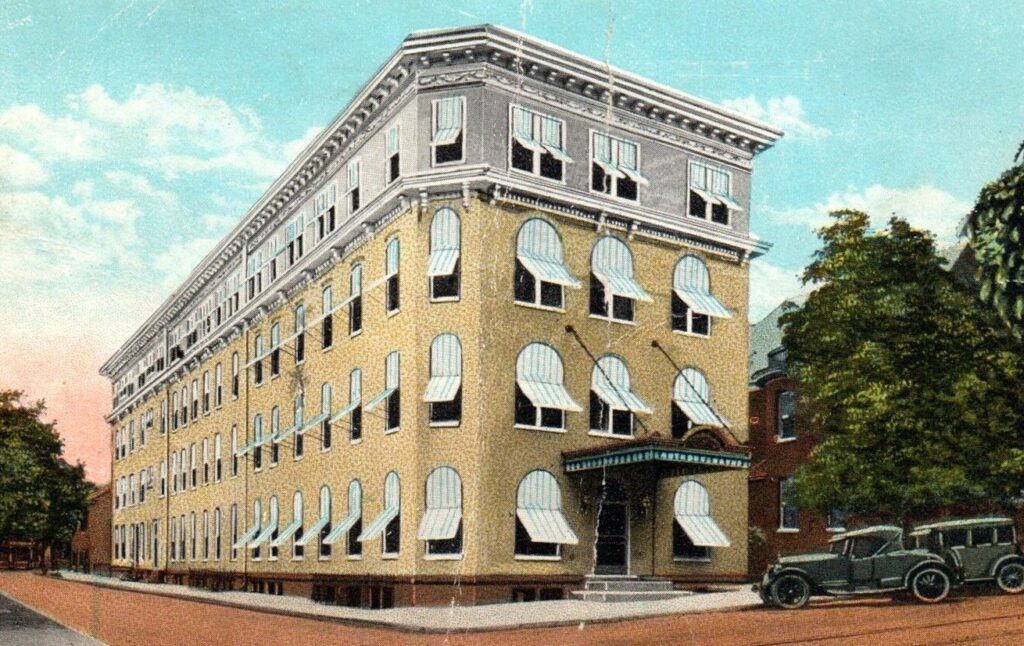

Leading up to the 1924 contest, a local conservative women’s group hosted an event at Republican Party headquarters, inside Waynesboro’s Anthony Wayne Hotel. A trio of female speakers told supporters the “principals of our party are right,” urging women to turn out for the election in full force and encouraging apathetic females to vote as well. American women were given constitutional voting rights only four years earlier.

Despite firm opposition to liberal principles, these women wanted a victory based on a solid conservative platform, not harsh rhetoric. They urged followers to “use care when slinging mud.” Their final message: vote a straight GOP ticket in 1924.

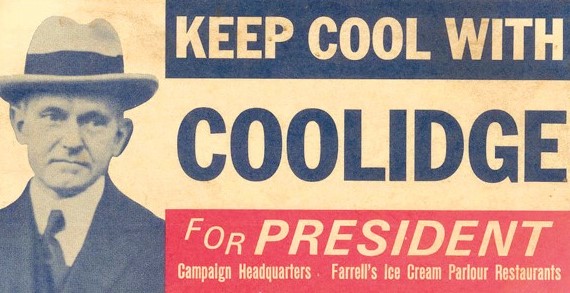

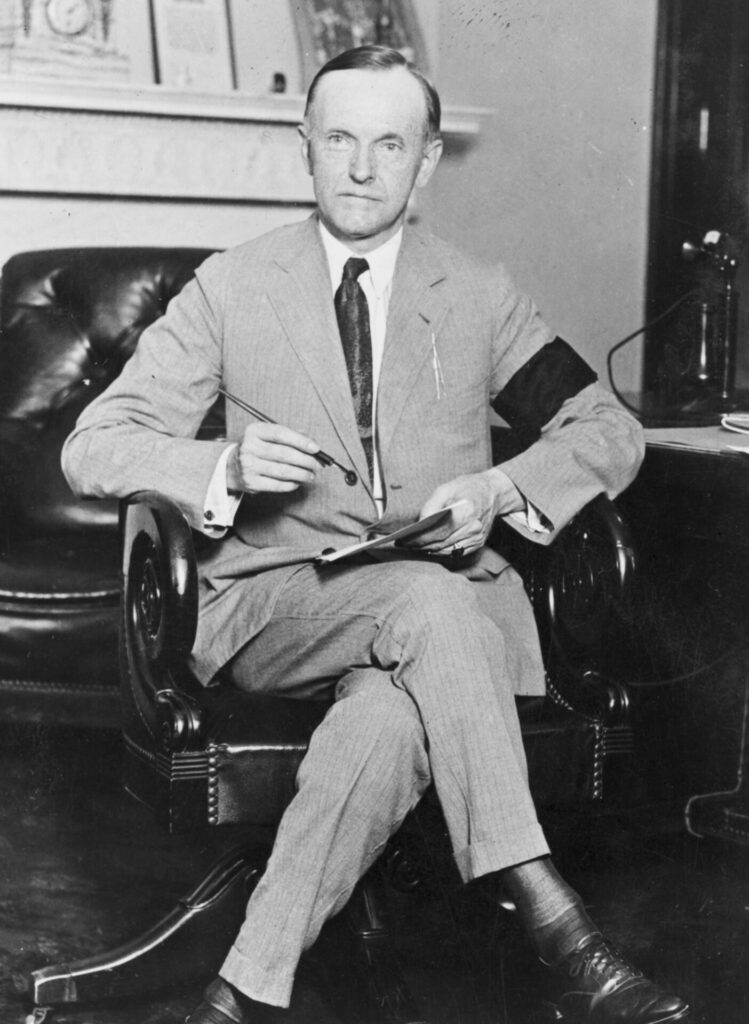

Living in the White House 70 miles away was Republican President Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge hailed from New England and exhibited a mild-mannered temperament. Many Americans called him “Silent Cal.” He was a man of such brevity that a reporter once bet him he could make the 30th President say a sentence containing more than three words. “You lose,” Coolidge said.

The former Massachusetts governor was elected Warren Harding’s vice president in 1920 and assumed the presidency after Harding’s sudden death in 1923. As the shocked country reeled from the tragedy, Americans eventually learned Coolidge and Harding were miles apart as leaders.

Coolidge’s governing philosophy was a hands-off approach, but he also proclaimed: “The business of America is business.” During the carefree 1920s, his laissez-faire style gained widespread conservative support, and Coolidge chose to run for President in 1924 on his personal merit. Republicans nominated Silent Cal at their national convention. Their campaign slogan: “Keep Cool With Coolidge.”

But that summer, another tragedy struck the White House. President Coolidge’s son, 16-year-old John Calvin Coolidge Jr., became ill. The young man was like his father, with a dry wit and a penchant for hard work. Calvin Jr. attended Mercersburg Academy, so the boy was known and liked in Franklin County.

That July, Cal Jr. played sockless tennis with his brother on the White House lawn. During the game, Cal developed a blister on his toe. The boy kept his injury a secret, and the wound worsened into a staph infection that later turned septic. In an era before penicillin, the young Cal’s condition quickly turned dire. Cal Jr. was rushed to Walter Reed Hospital, where he died on July 7, 1924.

A United Press reporter described the awful scene in Washington: “The curtains are drawn in the East Room of the White House. The President’s young son lies dead within.” Franklin County mourned the loss of an excellent student with a sweet disposition. Cal Jr. had one year remaining in his local studies at Mercersburg Academy. President Coolidge went forward with his campaign, a heartbroken man.

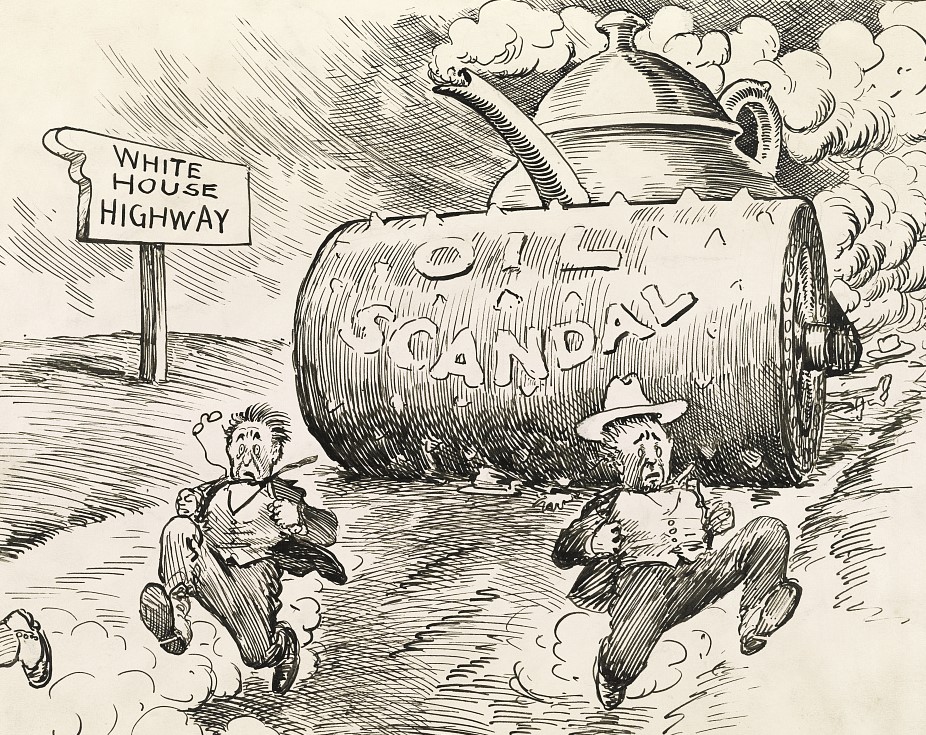

At first, in the national campaign, it seemed any Democratic nominee would hold an advantage over Coolidge. Harding’s freewheeling administration was scandalous. The Teapot Dome affair became synonymous with corruption, as one Harding official became the first-ever cabinet member sentenced to prison.

Later, after Harding’s death, public revelations of womanizing during his marriage (which included a child’s conception in his Senate office with a 20-year-old mistress) dragged Harding’s reputation to deeper depths.

Democrats tried linking Coolidge to Harding’s messes, but the new President was a devoted husband, and it was never proven Coolidge had any connection to the administration’s graft. The Democratic platform said: “The nation is appalled by revelations of political depravity” under recent Republican leadership. “A vote for Coolidge is a vote for chaos,” Democrats warned.

However, in 1924, the Democratic Party was in disarray. They staged a historically indecisive national convention at Madison Square Garden in June and July. Taking place over 16 long days and after casting more than 100 ballots, they couldn’t decide on a nominee.

Finally, on the 103rd ballot, they picked a compromise dark horse candidate, John W. Davis of West Virginia. Some Cumberland Valley locals recognized Davis, but to most countrymen, the former U.K. Ambassador was unknown. After the convention, celebrated humorist Will Rogers quipped: “I’m not a member of any organized party, I’m a Democrat.”

Locally, political interest was piqued by the debate over protective tariffs, which Republicans favored but Democrats denounced, saying they penalized agriculture and caused harsh conditions for farmers.

However, a left-leaning wing of the Democratic Party thought these positions were still too weak, and they split from the Dems, forming the Progressive Party. They nominated Wisconsin’s Robert LaFollette as a third-party presidential nominee.

In black typeface, local media predicted a “heavy turnout in state” as the election neared. Four theories were cited. The recently inaugurated women’s vote would prove influential, the third-party candidate might appeal to the area’s agrarian interests, get-out-the-vote caravans would encourage new voters and a higher interest in Pennsylvania regional candidates could inspire a larger turnout.

Meanwhile, Waynesboro’s Record-Herald covered everyday life during election season. A local railroad engineer complained about the cows that constantly crossed over area railroad tracks. On the Sunday before the election, a visiting evangelist drew a large crowd at the Salem Reformed Church.

Waynesboro residents highly anticipated election results, and organizations boasted of “elaborate plans” to keep them informed. At the nearby Republican headquarters, a newfangled radio hookup promised to bring the latest tallies to Franklin County ears. The Elks Club planned to show results on a screen outside its building. At Waynesboro’s Arcade Theatre, they too would project vote totals on the big screen, along with a movie playing that week titled “Manhandled,” starring Gloria Swanson.

On Election Day, Nov. 4, 1924, Waynesboro’s daily newspaper honored the first voters by printing each citizen’s name from all seven precincts. The press noted local industry workers would wait until early evening to vote after their daily toil ended.

Also on the local ballot were candidates for Pennsylvania state treasurer and auditor general, and regional office-seekers for Pennsylvania House and Senate seats. The newspaper promised election results from the county and around the nation in the next day’s edition.

On Wednesday, Record-Herald headlines showed no lingering suspense after the 1924 election. “A Clean GOP Sweep in Franklin County” and “Biggest Vote In History” were announced. Voting in Waynesboro’s precincts was a “record breaker” with 2,963 residents casting ballots.

One minor Democrat success story was Waynesboro candidate Joseph Guy, who ran for state Legislature. He won the Borough’s vote share by 188, but in other localities, his opponent, Republican D. Erskine Witherspoon, made up that margin for an easy victory.

Republican Nelson Bonbrake won the 33rd State Senate seat. The Chambersburg candidate had a fine pedigree as a successful attorney and Cornell graduate. Bonbrake was re-elected in 1928, but in 1930 died in office from a sudden stroke.

When the 1924 election dust settled in Franklin County, the Democrats won nothing.

Republican Calvin Coolidge was elected President, and 58 percent of Franklin County voters supported his candidacy. Pennsylvania went even higher for Cal, giving the incumbent a 65 percent share. Coolidge won a vast majority of American states outside the former Confederacy, winning 382 electoral votes to Davis’s paltry 136. Local voters rejected the Progressive third-party candidate LaFollette, giving him only a 6 percent share.

A historian later argued the 1924 election marked the high tide of American conservatism. Even Democrats that year lobbied for limited government, reduced taxes and less regulation. Immigration was a hot issue then too, as the Democrat’s platform pledged to maintain their position “in favor of the exclusion of Asiatic immigration.”

In following years, Pennsylvania developed into a swing state, with larger urban progressive populations balancing conservative rural voters. Franklin County has remained a bastion of conservatism to this day. County Republican voter registrations outnumber Democrats by more than 2 to 1.

The 2024 election showed much higher Franklin County support for President-elect Trump (71 percent) than state and national voters. County and state row offices were swept by GOP candidates this year, identical to 1924.

On Election Day 1924, as women enjoyed new voting privileges, two national feminine candidates made history as the first women elected as governors. But neither candidate was a political powerhouse outright, as both were wives of former state governors.

In Wyoming, novice politician Nellie Ross became the party nominee after her husband William died from a ruptured appendix only weeks before the election. Miriam Ferguson won the Texas governorship that year, running as a surrogate for her spouse, James, who was impeached and barred from office. Both women lost their re-election campaigns. In 2025, 13 women governors will administer U.S. states, a new record, but Pennsylvania hasn’t yet elected a female to that office.

Kamala Harris ran in 2024 as the second woman in major party history to compete for the presidency. Her efforts fell short. Harris lost Pennsylvania, and only one female candidate prevailed for a statewide office. Republican Stacy Garrity won re-election as the state treasurer. The remaining victors in Pennsylvania state row offices were GOP men, as were the local Pennsylvania House and Senate winners, and the 13th U.S. Congressional candidate.

After winning in 1924, Calvin Coolidge completed his full presidential term, but his enthusiasm for public office waned. He didn’t seek re-election in 1928. After his retirement from politics, Coolidge wrote how Calvin Jr’s tragic death changed his outlook: “When he went, the power and glory of the presidency went with him.”

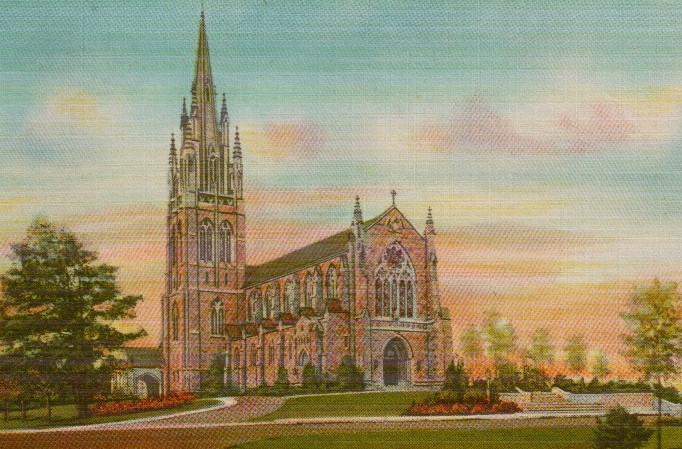

On November 25, 1924, Mercersburg Academy announced plans for a campus memorial garden honoring John Calvin Coolidge Jr. Earlier, First Lady Grace Coolidge laid the cornerstone for the Academy’s Irvine Memorial Chapel only a month before her son died. The heartbroken Coolidge’s later donated a cross to the beautiful new Chapel, which was dedicated on Oct. 13, 1926.