On a tragic Tuesday in May 1911, a volatile romance turned deadly, and two lives ultimately ended. That horrific day triggered the end of an era in Franklin County’s criminal justice system.

Sarah “Sadie” Hurley was born on Valentine’s Day 1881. At age 17, shortly after her father died, she married Reuben Mathna in Hagerstown. They had one daughter together, but Sadie’s husband deserted their marriage after 18 months. Sadie was a petite woman with dark hair typically gathered in a bun atop her head. The attractive and spirited woman was described by friends as energetic and industrious.

Born in 1869, William Reed was a Mont Alto resident who joined the Army in 1896. He served in the Philippines during a short military career. After his service, Reed found work at several Waynesboro industrial shops, including at Frick Company. Most co-workers said he was a well-spoken and pleasant man when not drinking. A local woman described Reed as “rather good-looking, with blue eyes, light hair and a complexion showing an outdoor life.” Reed never married.

Sadie and William met in 1908. Their developing romance became an on-again, off-again affair. The couple ultimately lived together in Waynesboro for a few months in 1910, but then Sadie left to live with her mother in Chambersburg. Still, the couple continued seeing each other on weekends after Sadie took a cooking job at Mont Alto’s Forestry Academy and moved into quarters there.

Early in 1911, William asked Sadie to move back in with him, and she refused. Friends noticed Reed’s increasing agitation and saw a dark turn in his temperament. In March, after visiting Sadie’s workplace and finding her absent, Reed told her co-worker, “That woman will fool around until I kill her.”

In May, Reed took a trip to Ohio with a friend, but returned early when his buddy became disgusted with William’s behavior. He said Reed was drinking heavily and paced the floor like a caged animal. Once back in Pennsylvania, Reed tried revisiting Sadie, but she was supposedly in the company of another man.

A few days later, at Reed’s request, a friend borrowed a .38-calibre revolver and then lent it to William Reed.

Reed took the train to Mont Alto on May 9, 1911. He entered the rear kitchen door of the Forestry School’s Wiestling Hall and found Sadie alone inside. William demanded the return of some keepsakes, including pictures, letters and his Army discharge papers. Sadie refused, and a heated argument ensued.

Finally, Sadie relented and retrieved Reed’s property. But when she returned to the kitchen, she shoved his items inside the stove and burned them. According to Reed, their shouting increased when Sadie picked up a coffee grinder and threatened to smash it over his head.

Reed pulled his borrowed revolver and fired three times. A trio of bullets hit Sadie. One struck her face, another pierced her heart. Sadie stumbled into the dining room, leaving a trail of blood, then fell to the floor. Alarmed co-workers rushed into the building after hearing shots and screams and carried Sadie upstairs. She moaned before taking her last breath, only 30 years old.

Reed had escaped the building, and a witness heard him say, “I fixed her this time.” William gave the gun to a friend but turned himself in to the local magistrate — who was also his Uncle.

When Reed’s trial began on Sept. 7, 1911, his attorneys stated that alcohol inflamed their client’s mind during the shooting. They argued William Reed was temporarily insane when he committed the crime.

Reed’s fate rested in a jury of 12 peers, which included a storekeeper from Quincy, a carpenter from Chambersburg and a butcher from Waynesboro. Retiree Jacob Mowery from Mercersburg served as the jury’s foreman.

Throughout the trial, spectators noticed Reed’s calm demeanor. A local newspaper said of the defendant: “His face did not change in any of its lines; there was not a tremor in the body that has so much military erectness about it.” Reed sat stoic, “maintaining his remarkable composure in the most trying moment of his existence.”

Inside a packed and humid courtroom, Reed took the stand and insisted he acted without premeditation. “I only fired the gun to scare her,” he said. Reed’s defense team asked the jury: why would Reed buy a round-trip train ticket and also leave the scene before knowing whether Sadie was dead if he schemed to kill her?

However, several witnesses contradicted the defense, saying they heard Reed’s earlier threats. The prosecution said the defendant’s continuing jealousy over Sadie created the malice that formed a premeditated motive. The jury would decide whether the crime was a planned murder in the first degree, the worst offense, or if the defendant was guilty of a lesser crime of passion. Reed’s life hung in the balance.

The jury began deliberations on a Saturday at 6 pm. On the first ballot, only one juror voted for a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter, but subsequent votes teetered between first and second-degree murder verdicts. Finally, after 26 continuous hours of deliberation and 14 ballots, the courthouse bell rang at 8:19 pm Sunday, signaling a decision.

A crowd rushed back to the Chambersburg courtroom. The judge asked for the jury’s verdict. Foreman Mowery said in a calm voice: “Guilty of murder in the first degree.” Each polled juror agreed with the official decree. Reed was a convicted murderer facing the death penalty.

Reed appealed the verdict on Sept. 25, with his attorneys listing 15 legal mistakes that demanded a new trial. The appeals process was swift. On Oct. 3, that first request was denied. The case was then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Jan. 12, 1912. That chamber also turned down Reed’s request. On March 20, the Board of Pardons refused to commute Reed’s sentence. On April 1, the governor signed a death warrant.

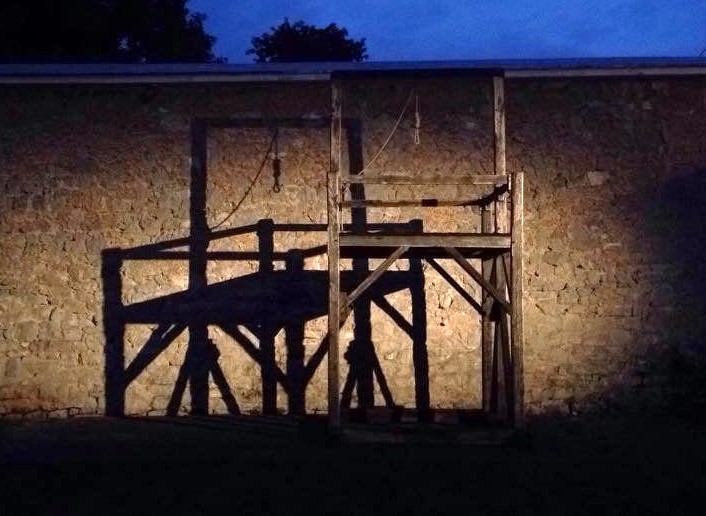

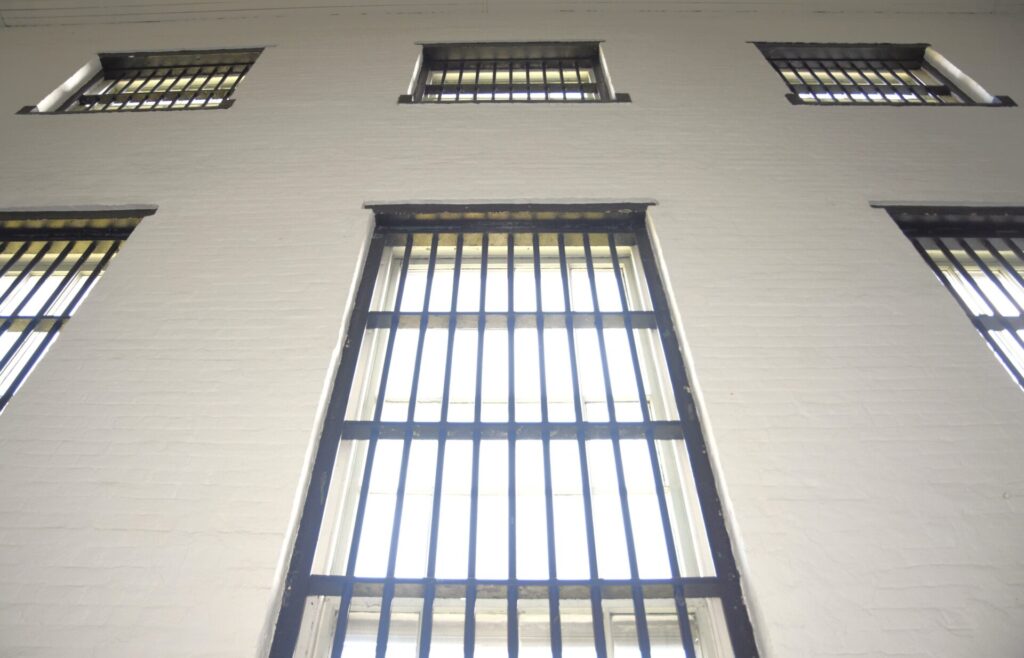

Local citizens were morbidly curious about Reed’s upcoming hanging. The most recent county execution had been 33 years earlier. Two men were hung in April and June of 1879 for separate murders. While the execution wouldn’t be public (Pennsylvania was one of the first states to ban civic hangings in 1834), it didn’t stop some people from trying to witness Reed’s punishment.

On judgment day, April 30, 1912, a local paper noted Reed spent a quiet and restful evening before his doomsday. An impromptu prayer service was held, and later, Reed prepared a final statement that said in part: “I am sorry for my deed. I forgive everybody and hope all will forgive me for anything I may have done to others.”

Outside the prison’s high walls, oblivious to drizzling rain, a thousand people gathered. A few climbed trees or poles to secure better views. Consistent with his mood throughout the trial, Reed remained calm as he was led to the gallows wearing a black suit and blue tie. The hangman slipped a dark cloth over the condemned man’s head. Reed’s hands were tied behind him, and his ankles were bound together. No words were exchanged on the wooden platform.

At 10:06 am, Reed fell. After one minute, the coroner detected no pulse, and he pronounced the murderer dead nine minutes later. Fifty witnesses were present, including jury members, the sheriff, the county coroner and a Waynesboro reporter named H.L. Grimm. Noting the swift death and lack of any struggle from Reed, one prison official pronounced the hanging as “humane as such things can be.”

They placed Reed’s body in a gray coffin and transported his remains to a Mont Alto Cemetery. A few relatives attended his graveside service. Then, William Reed was interred beside his parents.

Victim Sadie Hurley Mantha was already in the ground for nearly a year, buried at Roxbury Union Cemetery. An estimated 2,000 people viewed Sadie’s body before her funeral.

The following year, Pennsylvania revoked a county’s legal authority to execute prisoners. From 1913 forward, the Commonwealth administered all death sentences at state prisons, using a new method, the electric chair.

William Reed’s execution was the last hanging conducted in Franklin County. But he wasn’t the final man put to death for a crime committed within the county. Ralph Hawk owned that notoriety in 1938.

Hawk’s crime was especially heinous. To avoid marrying Catherine Gelwix, he set her house afire on New Year’s Day. Catherine escaped the flames, but her mother and sister perished. Twenty-one-year-old Hawk was convicted of arson and double homicide and sentenced to death. He died in the electric chair at Rockview State Prison on March 28, 1938, the last state prisoner executed for a Franklin County crime.

Pennsylvania used the electric chair until 1962. After capital punishment was ruled illegal, all U.S. executions halted. However, in 1976, the death penalty was reinstated. Since that year, only three men have been executed in the state, all by a new method chosen in 1990, lethal injection.

In 2015, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf announced a moratorium on executions. Current Gov. Josh Shapiro retained that stay when he took office.

For most of its history, Pennsylvania was diligent in carrying out executions. Since 1693, the state put to death more prisoners (1,043) than any other state except for Virginia’s 1,361 and New York’s 1,130. Both those states have outlawed capital punishment, but executions are still legal in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania historical archives provide a macabre listing of doomed prisoners’ age, gender, race and occupation. Almost all were men. Prisoners as young as 16 were executed, and others as old as 72 died. Various occupations listed for these convicted criminals include bowling pin boy, voodoo doctor, speakeasy operator, milkman, and banana dealer. Hanged at age 42, William Reed’s occupation is listed as a laborer.

Reed’s execution at Chambersburg’s Franklin County Jail was the last, but the facility stayed in service until 1970. Now referred to as the “Old Jail”, the retired building on King Street is a National Register historic site open for public tours. Outside, in the shadow of 20-foot-tall limestone walls, the gallows where William Reed died still stands in the former prison yard.

In present-day Mont Alto, on the Penn State University campus, Wiestling Hall also survives. It is the oldest structure on all PSU grounds. Local lore says on quiet nights Sarah “Sadie” Hurley’s ghost wanders the interior rooms, still present at the tragic site where William Reed stole her life.