The earth belongs to the living, but sometimes, parcels of land belong to the dead. After the American Civil War, a progressive era brought new burial practices and post-mortem customs, offering citizens alternate choices to bury and remember their loved ones. The concept of the cemetery was born.

During earlier 1800s periods, the dead were interred adjacent to churches in cramped graveyards. Those small city lots were limiting, but burials were concentrated around a deceased person’s religious faith and respective properties. Then, in 1831, a resting place called Mount Auburn Cemetery was established in Boston, setting a trend that eventually revolutionized how the dead spent eternity.

In Maryland, several city cemeteries were placed on then-rural lots, affording increased acreage to accommodate larger numbers of evenly spaced graves and also providing a scenic atmosphere of winding lanes, natural landscapes and open vistas. Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery and Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery are two early examples. Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown was a third creation during this period and is the largest of this state trio.

The first meeting of the “Hagerstown Cemetery Company” took place in November 1865. A group of local citizens planned to establish the area’s first public cemetery, where people could bury loved ones regardless of race or religion. The first order of business: find a suitable land tract outside the bustling confines of Hub City’s downtown.

Dr. John A. Wroe was prosperous in Hagerstown and owned the perfect lot for the proposed cemetery. After attending medical school Wroe opened a Hagerstown practice in 1843. The doctor treated both Confederate and Union soldiers during the Civil War. Local lore suggests he hosted Robert E. Lee for a home-cooked Maryland dinner during the conflict.

Dr. Wroe lived in the fashionable Prospect Street neighborhood but also owned a farm property on South Potomac Street, called “Wroe’s Hill.” He agreed to sell up to 40 acres to the new enterprise for $250 per acre. On March 16, 1866, the new cemetery was chartered, and to romanticize the property’s new brand name, it was called “Rose Hill.”

That Spring, renowned Baltimore landscape architect John Wilkinson came to Hagerstown to lay out a master plan. He designed a garden-style cemetery, which worked with the rural land’s natural topography, instead of imposing a grid of straight lines on a rigid system of gravesites.

More than 150 years later, Wilkinson’s artful plan is still evident at Rose Hill. The cemetery has become a microcosm of Hagerstown and Washington County history. This pastoral ground provides a resting place for the area’s prominent leaders from politics, the arts, the military and industry, plus thousands of Hagerstown’s ordinary citizens. But the cemetery’s park-like setting also contains architectural features that highlight the changing fashions of local culture, both in life and in death.

Rose Hill was once a rural location, but as Hagerstown continued its growth during the latter 1800s, the city grew southward and bypassed the cemetery. A reminder of the property’s agrarian past remains within the cemetery’s boundaries. A cylindrical stone tower, resembling a mini-version of the “first” Washington Monument near Boonsboro, stands among the headstones. It isn’t a memorial but simply an old water tower from the original farm. Founded with 24 total acres, Rose Hill now encompasses 102 acres.

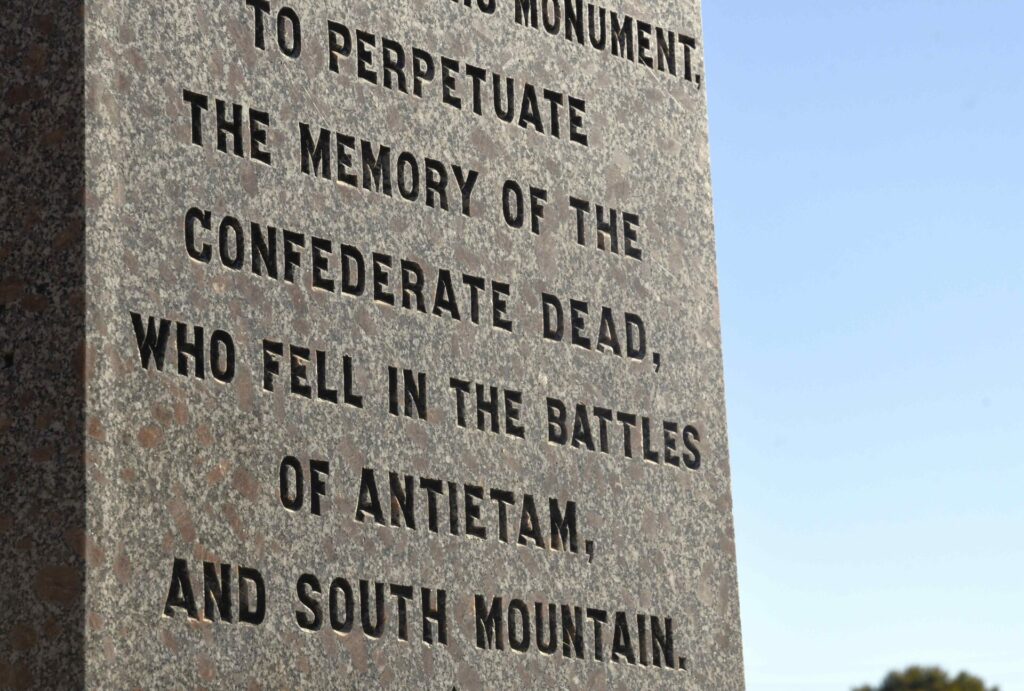

With Hagerstown’s proximity to major Civil War battles, traces of that historical period are expected at Rose Hill. However, the cemetery didn’t yet exist during that great conflict. Thousands of Confederate soldiers died during epic battles at Gettysburg, Antietam, South Mountain and Monocacy, and many were buried where they fell.

A movement to move those brave men to a common burial site materialized during Reconstruction. The State of Maryland purchased acreage at Rose Hill to accommodate them in 1871. This cemetery within a cemetery is called the Washington Confederate Cemetery.

When completed in 1877, 2,468 soldiers rested there. Only 346 of those men were identified. A monument erected that same year was named the Statue of Hope. The figure of a woman, 19 feet tall, is clothed in a flowing robe while leaning on an anchor. A single star sits on her brow as she faces the mass burial site. There are no individual tombstones here. Over the years, other Confederates were buried there and several re-dedication ceremonies celebrated. Former President Eisenhower presided over one such occasion in September 1961.

After the Civil War era, African Americans struggled to receive rights that new Constitutional Amendments guaranteed them. Voting was one privilege, and a man buried at Rose Hill is known as a pioneer in that civic task. His name was Jacob Wheaton. Wheaton (1835-1924) was the first of his race to vote in Maryland when he cast a ballot in Hagerstown’s 1868 city election. He was later the first Black man to serve on a jury and as a court bailiff.

Another prominent African American burial is William O. Wilson. Wilson (1869-1928) was a member of the U.S. Army’s 9th Cavalry Regiment– commonly referred to as the “Buffalo Soldiers”– an elite Black mounted unit that saw action during the Indian and Spanish-American Wars. Wilson won a Medal of Honor for his service. In 2003, his surviving daughter donated that medal to the Maryland African American Museum.

Scattered among this rolling landscape are various notable Washington County former citizens from every walk of life. Two former Maryland Governors rest here. Gov. William Hamilton served as chief executive from 1879-1883, while Preston Lane Jr. was in office from 1947-1951.

Hiram Maxim is buried at Rose Hill. Maxim (1869-1936) was an amateur radio pioneer and also invented a silencer for firearms. His father invented the Maxim Machine Gun, and his Uncle Hudson was the originator of ballistic propellants.

The owner of the famous Moller Pipe Organ Company, Mathias Moller (1854-1937), is found at Rose Hill. His company was the world’s largest organ manufacturer for many years, completing more than 12,000 custom instruments until the company ultimately closed in 1992. Moller is entombed here with his family inside a small mausoleum. Rose Hill built its own stately mausoleum in 1918, which houses many of the area’s early notable citizens. By the 1950s, that building’s spaces had completely sold out.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, a company called Woodmen of the World sold life insurance policies to its customers which included a unique payoff. A policy guaranteed the insured a graveside monument after death, which resembled a tree trunk. Many of those memorials, resembling petrified wood, still exist at Rose Hill.

During its first century, Rose Hill was similar to other cemeteries of that age as talented stone masons and carvers created stunning statuary to honor the dead. Eventually, that handiwork became too expensive, and the tradition faded. Relics from that era are spread throughout the grounds today, offering glimpses of statues that braved the elements for decades.

Angels are a popular motif, symbols of a pleasing journey in a spiritual afterlife, and some of these winged gems are bleached pure white by persistent Maryland sun and wind.

As the seasons change, so does Rose Hill. Mature trees shade gravesites, and when their leaves turn color and fall to the ground, they remind humanity that earthly existence is temporary. This cemetery also has living residents. On the grounds, squirrels scamper as they prepare for winter, birds hop from trees to perch atop tombstones, and shy deer appear at dusk to walk among the monuments.

The business side of Rose Hill has changed with the times. The cemetery offers spaces for cremation, and more than half of deceased cemetery residents now choose that method as a quicker departure from their earthly shell. In another cemetery section, under a weeping willow tree, children’s graves are lovingly tended to honor lives that expired too soon.

The cemetery also offers various tours throughout the year, and promises new ones will originate soon, reflecting unique historic and cultural aspects of the Hagerstown area. Today, the city has a population of 43,527. As All Saints Day approaches, Rose Hill has 45,000 burials, an entire city of past spirits and souls who helped shape modern Washington County.

Rose Hill Cemetery is located at 600 S. Potomac St. Visiting hours are dawn to dusk, and walking tour brochures are available onsite. More information about upcoming programs, history and genealogy research, office hours and cemetery services are available by calling 301-739-3630 or visiting online: rosehillcemeteryofmd.org.

During the holiday season, Rose Hill glows at dusk with candle luminaries burning on the second Friday in December every year, a fitting tribute to departed Hagerstown souls that once flickered with inner light.