On a Friday evening in 1915, two trains sped toward each other on a single Maryland railroad track. The date was June 25th. One train was the Western Maryland Railway’s Blue Mountain Express, a passenger train headed west toward Hagerstown. The second locomotive was the Number 10 mail train, traveling east to Baltimore.

Both conductors were aware of the opposite train approaching and even knew each other by name. Since a regular safety protocol existed, which usually allowed these two trains to pass without incident, neither railway official had reason for concern.

However, on this day, the westbound passenger train was running behind schedule, and a vital human element in the railroad’s right-of-way safety system would fail. The two trains headed for disaster.

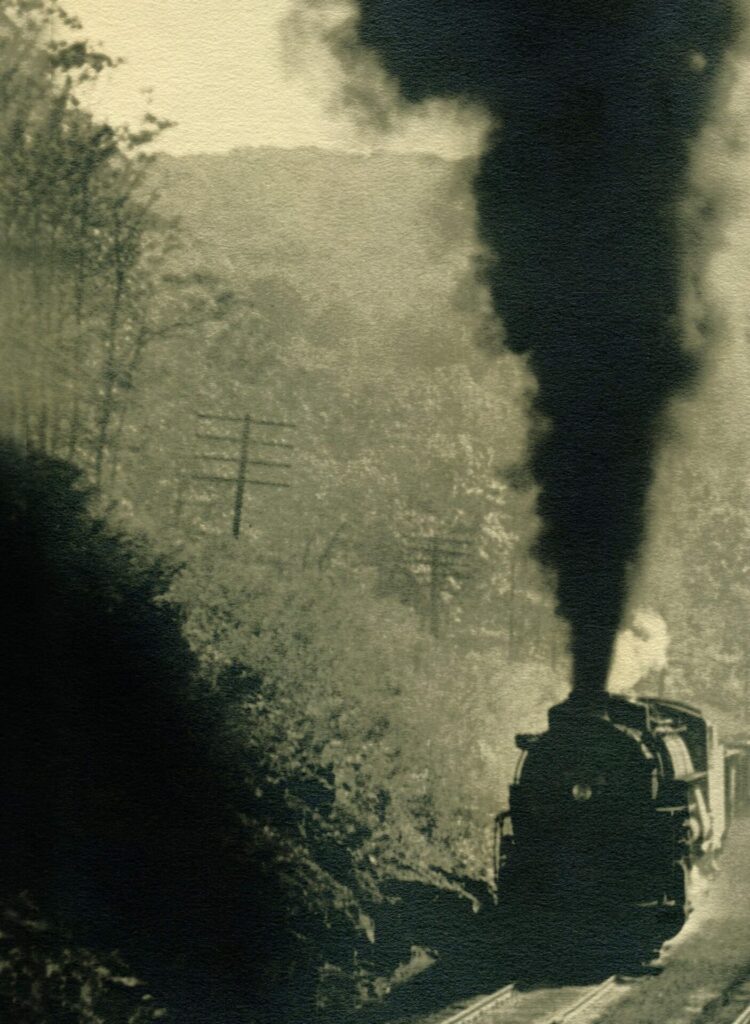

During that era, automobiles and airplanes hadn’t yet replaced trains for long trips. A journey over the Appalachians showcased trains’ ample horsepower, and passengers enjoyed the thrill of a ride along the rails. The Western Maryland Railway originated in 1852, and by the early 20th century had established a reliable regional reputation for hauling coal, freight and passengers.

Also, during this period, cool mountain air brought many city dwellers to Blue Ridge resorts each summer. These tourists traveled to escape the lowland heat and to visit attractions like Pen Mar Park, which entertained guests with recreational pursuits and popular big-band music. Mountaintop hotels pampered travelers with accommodations that offered panoramic vistas.

Back on that tragic day in 1915, a teenager named Charles Eyler waited with his friend at the Thurmont train station at 5 p.m. The two delivery boys regularly picked up daily Baltimore newspapers from the westbound train’s baggage car. On this day, the Blue Mountain Express was tardy.

When the train finally arrived, the boys noticed a one-legged baggage handler named Luther Hall was in a foul mood. He growled he’d be late for supper. The young duo grinned and grabbed their papers. They started their local route, clueless about what would happen next.

The eastbound train headed downgrade toward Thurmont. The conductor awaited customary right-of-way instructions from the Hagerstown dispatch office. A routine pull-over to a siding at Flint was anticipated to let the western train pass. But on this day, the dispatcher mixed up these critical orders.

The west-traveling train, making up for lost time, chugged up the mountain grade with eager passengers onboard; a summertime weekend approached. They included Mrs. Edwin Chipchase and her 27-year-old son, Walter. This mother, who was handicapped, couldn’t ride comfortably in the passenger section, so she rested on a cot in the baggage car instead. Walter sat by her side.

Both conductors realized other trains routinely ran off schedule, but it typically wasn’t their concern. They trusted dispatch in Hagerstown to issue proper instructions. Neither conductor communicated with the train approaching from the opposite direction. On that day in June, they traveled blind.

In Hagerstown, a dispatcher named Edgar Bloom sat at the routing controls that day. The overworked Bloom made a mental error, and his orders for a normal pull-over to the siding were communicated incorrectly. As a result, neither train stopped to give the other right-of-way passage.

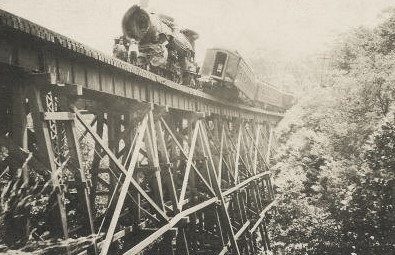

Then, the timing of the approaching trains, with unknowing passengers aboard, turned from bad to worse. A railroad trestle ferried trains over a steep ravine west of Thurmont. This high bridge, with spider-like support beams, was the only course for crossing a nearly 100-foot-deep gorge.

Sharp curves blocked a clear view on both approaches to this bridge. These conditions made it a dangerous crossing when operations ran smoothly but would prove more hazardous for these dual hulking machines aimed on a collision course.

The two trains rounded these blind curves. Once they simultaneously entered the bridge and saw each other, it was too late to stop the powerful momentum of their locomotives.

As they finished their paper route, the two teenagers heard the ominous sound of a train whistle, stuck open in a wailing moan. The boys recognized something was wrong and raced up the tracks. They encountered a terrified railroad flagman sprinting from the west, who shouted about a terrible crash. When the boys arrived at the bridge, they witnessed the tragic scene.

The two trains had crashed head-on in the middle of the railroad bridge. Red hot coals from each train’s boilers spit out fiery embers, threatening to set the wooden trestle ablaze. The baggage car from the westbound train had decoupled during the collision and hurtled off the tracks; it lay smashed down in the ravine. On the high bridge, a Pullman car barely connected to its train dangled airborne off the tracks to one side, teetering on the brink of a disastrous fall.

People from the countryside gathered at the crash site to assist in the rescue. Most agreed it was a miracle the bulk of both trains remained on the tracks and didn’t fall from the bridge. The mighty collision locked the two train’s engines together and this fusion of hot metal likely saved them from plunging into the deep ravine.

Amid chaos and destruction, it was quickly evident multiple people were injured and some had perished. At first, arriving bystanders were unsure how to help out on the bridge, enveloped in a haze of twisted and steaming iron. Looking downward, the safest traverse to reach that mangled baggage car needed calculation.

Several doctors appeared on the scene, including Victor Cullen and the Western Maryland Railroad physician, E.C. Kefauver. Severely injured passengers were rushed to the hospital in Hagerstown, while others less hurt sheltered in nearby homes.

Since the collision’s force demolished the front of each train, the worst injuries occurred there. Coleman Cook, the engineer of the eastbound train died instantly. His counterpart, Engineer Frank Snyder, was thrown from his train and badly injured, suffering two broken legs. C.R. Fritz and J.R. Hayes, firemen from each train, who fed coal to the hungry boilers, were also fatally wounded. Another fireman made a last-second leap from his train and landed in a tree 50 feet below, but survived.

Most passengers who rode behind these railway men were more fortunate and incurred less serious injuries. But unlucky people confined in the baggage car, decoupled from the rear of the westbound train, were doomed. When it fell off the bridge, one-legged baggage man Luther Hall was inside and died from his injuries. The frail Mrs. Chipchase also perished. Rescuers eventually found her son, Walter, gravely wounded, and he was taken to a hospital. He died later that night.

In the following days, the Western Maryland Railway issued a formal statement. They regretted the fatal incident. But they pointed out that most of the dead and injured were railway employees. If Mrs. Chipchase and her son had ridden with the rest of the passengers, they likely would have survived. The bridge held firm, and the sturdy mass of their locomotives shielded most people onboard. The accident could have been much worse.

Later, at an inquest before interstate commerce inspectors, railway officials and the state’s attorney, a distraught Dispatcher Bloom detailed fateful errors that led to the accident. He testified his job directing trains was more work than one man could safely handle, but he bravely accepted his professional culpability.

All told, six people lost their lives in that horrible Maryland railroad crash and scores were injured. People traveled from neighboring towns to gawk at the awful site. This train wreck was a tragedy local witnesses never forgot during their lifetimes, including the 17-year-old paper boy Charles Eyler.

Throughout history, local railroad travel was predominantly safe. But later in 1920, a trolley crash killed a C.G. & W. Railway conductor heading down the mountain from Pen Mar when the car’s brakes failed. With advances in modern technology, most risks in railroad safety systems vulnerable to human error are now eliminated.

The intelligent engineering and physical might that powers trains over steep mountains are still impressive today. Trains continue to travel this same railway route. The section containing the ancient crash site is located on Maryland Highway 550 between Sabillisville and Thurmont. But the railroad bridges have been modernized.

Many railroad enthusiasts enjoy the nostalgic sight of trains passing through the area. Since 109 years have passed, they have no firsthand knowledge of the fateful collision on these railroad tracks in June 1915, only the stories passed down by those who witnessed this transportation tragedy.