An area encompassing 1.9 million acres, including a portion of Franklin County, is now included in a new designation called the Kittatinny Ridge Sentinel Landscape, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro has announced.

This unique conservation program is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense and other federal agencies and coordinated through state and local partnerships.

The Kittatinny Ridge Sentinel Landscape will impact local private landowners and the military base also located within the KRSL, and details will soon unfold as this extensive program takes shape.

The Sentinel Landscape program was launched in 2013. This national program’s designated areas are described by the government as places where “conservation, working lands and national defense interests converge.” There are currently 18 SL designations across the United States. Along with the recent KRSL addition in Pennsylvania, four other SL tracts were also commissioned in 2024.

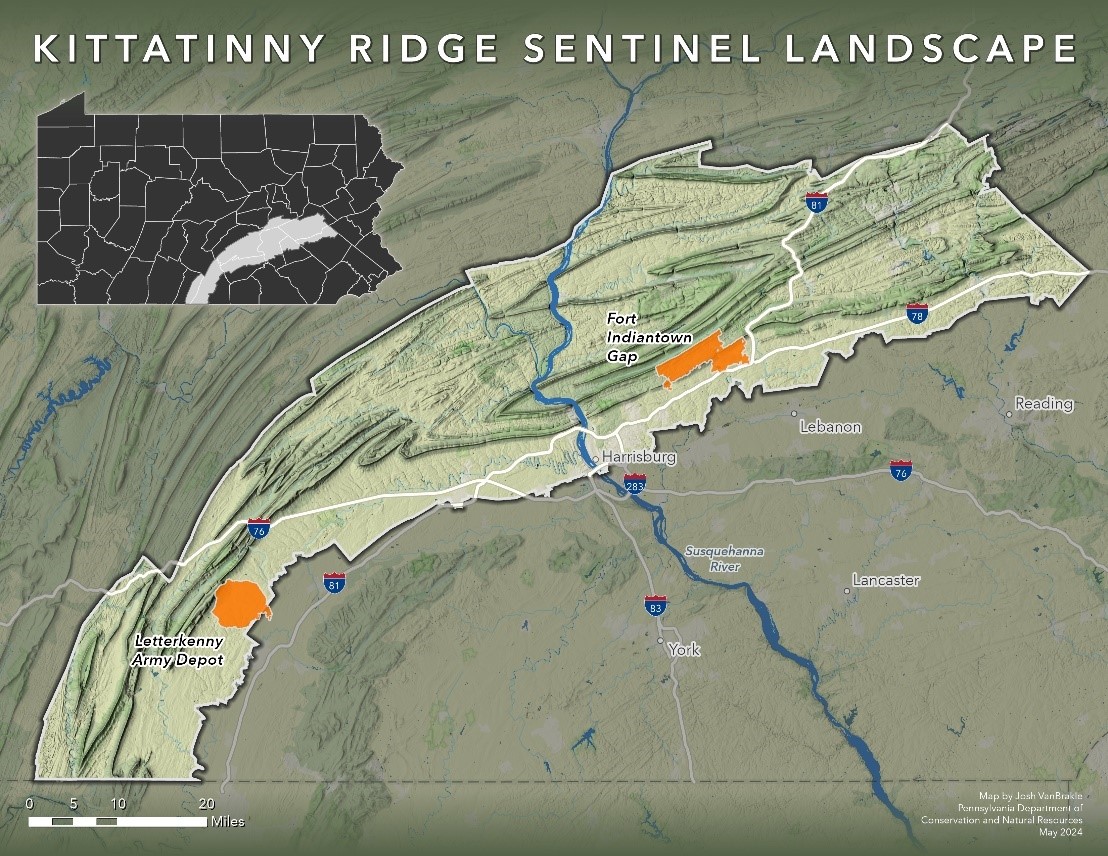

To qualify for a SL designation an anchor military base must be included within its borders. In Pennsylvania’s KRSL, two bases are involved. The first is Fort Indiantown Gap, located in Lebanon/Dauphin Counties, and it is considered the anchor facility. Letterkenny Army Depot is the second installation, headquartered in Franklin County near Chambersburg. Also within this KRSL designation are the Carlisle Barracks and the Naval Support Activity facility in Mechanicsburg.

Most of the previously designated Sentinel Landscape areas consisted of a single base contained within smaller acreages. One example is the nearby Maryland SL designation called Middle Chesapeake, created in 2015, which has one base (Naval Air Station Patuxent River) and 67,625 SL acres surrounding it.

Pennsylvania’s Kittatinny Ridge had prior exposure to the conservation movement; it was designated earlier as one of eight significant Conservation Areas by the state. According to a Shapiro spokesperson, the large size of the new federal KRSL area shadowed this previously chosen state conservation area, using the same ridgelines and municipal boundaries as a template.

Long before it was designated as a Sentinel Landscape, the Kittatinny Ridge was celebrated as a significant natural area in Pennsylvania’s Ridge and Valley region. Kittatinny means “big mountain” and this 250-mile long ridgeline (185 miles are inside Pennsylvania) is recognized as one of the most biodiverse regions in the eastern U.S. This ecosystem is considered a climate resilient landscape that fosters clean water and is home to many endangered and threatened wildlife species. The legendary Appalachian Trail meanders for 160 miles through this ridge.

The Kittatinny Ridge is also a globally recognized bird area and hosts a vital raptor migration path. For Pennsylvania’s wild residents, the KRSL proposes potential protection for their habitat and travel routes. One particular Kittatinny Ridge species of interest is the eastern regal fritillary butterfly; its sole known population is near Fort Indiantown Gap. The U.S .Fish and Wildlife Service is involved in these SL species-saving programs, and so is Pennsylvania’s Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, among other conservation agencies.

As a starting point, the U.S. Army’s Compatible Use Buffer Program predated the Sentinel Landscape initiative. The buffer program advocated for similar buffering of neighboring private lands located close to military bases. This practice would promote a safer cushion between the military and the public but without the government buying any of that private land.

While the purposes of the newer Sentinel Landscape Program are broader, espousing more conservation goals, the Department of Defense’s main objective remains to prevent peripheral development from encroaching on its bases’ operations. Civilian proximity can adversely affect training exercises — light pollution is one example — and decrease military readiness. The SL program seeks partnerships to create lasting and mutually beneficial separation zones.

This ultimate goal involves many land use challenges since 83 percent of KRSL land in Pennsylvania is privately owned. The state owns the next largest piece of this pie at 14 percent. Factors such as interstate corridors, wildlife protection, hundreds of potential individual partners, 50 participating local/state/federal agencies and the military dealing with its past environmental blunders, are a few potential trials. These factors add complexity to implementing this ambitious Commonwealth program over such a wide swath of territory.

The vast scale of this newly formed Sentinel Landscape area in Pennsylvania includes more than 500,000 residents, thousands of businesses and homes, hundreds of farms, 160 municipalities in nine counties and partnerships with numerous conservation groups like The Nature Conservancy and Audubon Society.

Regarding this new KRSL designation, Lori Brennan, the executive director of The Nature Conservancy in Pennsylvania and Delaware, commented: “This is a significant conservation victory for one of Pennsylvania’s greatest natural treasures. The Sentinel Landscape designation will help advance large-scale voluntary and coordinated land protection and management efforts along the Kittatinny Ridge.”

Within a multi-agency framework, KRSL administrators hope to negotiate and foster intelligent land use by using incentive programs that will help private landowners employ sustainable use practices. These include farming, forestry, ranching and enhanced recreational areas. All these uses are compatible with the military’s testing and training activities at their respective bases. Currently, forests account for 1.1 million KRSL acres (58 percent of the total land area), and cropland has the second-highest share of this acreage with 25 percent.

Sentinel Landscapes’ proactive programs, which will be funded by grants through agencies such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Department of Defense and Department of the Interior, along with state, local and private funding, are designed not only to benefit the military’s training and self-preservation goals but also to assist the people, agriculture and wildlife that live and grow near their bases.

Inside the boundaries of the KRSL, Fort Indiantown Gap is the prime military base. FTIG is a 17,000-acre facility and one of the largest National Guard training centers in the country. During 2023, more than 139,391 personnel trained there. FTIG’s heliport is the second busiest in the USA, and its extensive air exercises require dark skies and open spaces to create proper conditions for realistic night training. FTIG is considered vital to national security.

While trying to protect local military bases and foster conservation in tandem, both federal and Pennsylvania Sentinel Landscape spokespeople stress that all fiscal programs and policy incentives within the program are voluntary. Private landowners won’t be forced to participate, nor will their land be taken by the government to increase the size of military bases.

These federal and cooperating agencies envision the SL program as a tool for private property owners and conservation groups to meet them where their interests overlap. However, the potential workings of the SL program are more difficult to quantify when private landowners have land use intentions that clash with the military’s goals.

Both Fort Indiantown Gap and Letterkenny are close to I-81, and this presents an existing challenge for the SL federal program — competing against its own creation, the Interstate Highway System. Interstates were championed in the 1950s by President and ex-Army Gen. Dwight Eisenhower. While in Europe, Eisenhower noticed Germany’s Autobahn. He recognized a super-highway’s potential advantages to protect the United States homeland by creating faster and more efficient military transportation mega-routes over an entire continent.

After being put into practice, these U.S. interstates also brought civilian development, easily seen today along the Pennsylvania’s I-81 corridor. Quick access to major highways was attractive to distribution-oriented industry giants. They constructed massive warehouses on thousands of acres of what once was farmland, and some buildings were a half-mile long. With those enterprises came increased civilian vehicle traffic, (Interstates 76/78/83 also pass through the KRSL) which caused further congestion and spurred other commercial development. These elements triggered additional encroachments to the military’s nearby installations, especially at Fort Indiantown Gap.

Protecting Franklin County farmland from additional transportation-based overdevelopment is an important topic among local 2024 political candidates. Contenders on both sides of the ideological spectrum have cited the recent warehouse growth along I-81 as a prime threat to prized fertile lands. Sentinel Landscape coordinators tout their program’s potential benefits to protect remaining Pennsylvania farmland.

A related challenge between SL interests and private development is zoning. This aspect could potentially impact landowners if municipal governments, working in partnership to further the SL program’s goals, change or create new zoning standards for businesses, housing or any other commercial development. Potential rezoning changes were mentioned by Gov. Shapiro’s administration as a possible solution to civilian encroachment around Fort Indiantown Gap’s borders.

In addition, the conservation water gets murky for other land tracts within the KRSL, as their zoning is still termed as “undefined.” A military aviation training hazard also on the radar is the potential for privately-owned ridgetop wind turbines erected for power production. They constitute a tall structure risk for military aircraft.

A significant backstory to the Sentinel Landscape program is the U.S. military’s past environmental record. This entails its large carbon footprint and its subsequent impact, not only around the globe, but in local communities.

In 1982, some Franklin County landowners outside Letterkenny Army Depot’s territory discovered their well water was contaminated with toxic pollutants, including “forever chemicals” known as PFAS. An investigation found that multiple sites within Letterkenny had dumped hazardous chemicals during earlier decades, and these contaminants had leached into the soil and groundwater and then escaped the fort’s confines.

What followed was a 35-year cleanup effort at Letterkenny with an estimated cost of $180 million. While the military faced the situation head on and the cleanup is considered complete, they still monitor local groundwater as a precaution. On Aug. 5, Harrisburg’s ABC27 News reported on water quality surveys conducted in April. The results indicated that nine of 88 local drinking water wells tested near Letterkenny still contained PFAS at levels that failed the mandated minimum safety standards issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The environmental cleanup Letterkenny faced was not an isolated incident. The Environmental Working Group is a Washington, D.C., based activist group specializing in the research of toxic chemicals and drinking water pollutants. This organization lists 770 hazardous waste cleanup sites that exist today within former and active Department of Defense installations, with 140 of those locations categorized as “most serious sites” for long-term cleanup by the EPA.

Long-term exposure to PFAS may cause significant human health problems and also taint irrigation groundwater used by farmers. According to EWG, “Despite these risks, the Department of Defense’s pace of cleanup is far too slow. Unless spending increases, contamination at these sites may not be addressed for 50 years or more.” They also noted that DoD testified before Congress and admitted that after five decades of cleanups, the agency still faced a $29 billion backlog.

Another issue with encroaching civilian populations near military bases is that these facilities often conduct live ammunition exercises outdoors and potentially dangerous activities indoors. On July 19, 2018, an unspecified chemical sparked an explosion at a maintenance building inside Letterkenny Army Depot. Two employees were killed, and others were seriously injured. Considering these factors, buffer zones encouraged by the military’s Sentinel Landscapes will enhance safety conditions for nearby civilians.

The government measures the success of its Sentinel Landscape program in part by the amount of grant money dispersed and acreage protected. At the end of fiscal 2022, the federal government program had spent a total of $660 million, combined with $341 million in state funds, $26 million in local funds and $142 million in private funds to affect 677,000 acres. With this collective sum of $1.17 billion, the average cost spent per acre was $1,728.

The vast size of the Kittatinny Ridge Sentinel Landscape brings another statistical comparison. This in-state acreage is larger than the State of Delaware’s total land area. Including Letterkenny’s 18,000 acres, combined with Fort Indiantown Gap’s similar base territory, the military’s holdings in this 1.9 million-acre KRSL constitute approximately 2 percent of the land targeted for encroachment protection. The military flies training missions over a much broader territory outside each base’s borders, so these open-sky acres are an additional aspect to consider in this lopsided military-to-private land ratio.

Local impacts of this Sentinel Landscape in Franklin County will likely be less impactful than in buffer areas surrounding Fort Indiantown Gap, which appears to have greater civilian encroachment threats. But this particular Sentinel Landscape encompasses a large chunk of Pennsylvania real estate. The SL program’s coordinators encourage the state’s landowners to investigate possible program benefits when considering future land use options for their properties.

For additional information on the Sentinel Landscape program, those interested may visit the website (sentinellandscapes.org/landscapes/kittatinny-ridge/). The natural history of the Kittatinny Ridge and its ecological importance is detailed on Pennsylvania’s DCNR website: dcnr.pa.gov/Communities/ConservationLandscapes/KittatinnyRidge.