When precipitous clouds hover over the nearby Appalachians, they release replenishing rainfall onto a diverse and dynamic ecosystem. Spring water also bubbles upward from beneath this forested landscape, and together these converging liquid resources create a watershed of wonder. Featuring contemporary names like Rattlesnake Run, Bailey Spring, Swift Run and the renowned Antietam Creek, these waters tumbling from the mountains have nourished the Cumberland Valley for eons.

In addition to feeding native flora and fauna, this water supply also serves as a lifeblood for human communities downstream. One of those towns is Waynesboro. In a process requiring persistence and ingenuity over many decades, these precious waters have been collected, sifted, cleansed and fortified.

Turn on the tap and this liquid gold consistently flows — clear, cold and wet. But this seemingly common resource should never be taken for granted. A closer look reveals many of the challenges overcome and accomplishments achieved by Waynesboro’s water system.

Despite the short 7-mile distance from its mountain origin to thirsty consumers, this watery journey has taken more than 140 years to reach the system’s current high standard. The history of Waynesboro’s water is a story of intelligent engineering and nonstop improvement.

In the early days of human settlement, people collected water by simple methods, mostly through individual efforts. Back then, homesteads sprouted near natural water sources, like a spring or a creek, since that supply was as vital as oxygen. A well was dug or a pump was installed, and water was collected in cisterns or stored using basic vessels.

Waynesboro once offered a public pump in its town square. Local legend suggests that during the Gettysburg retreat in 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee stopped at that spot to water his horse, Traveller.

As villages became towns and people congregated in larger numbers, more sophisticated water systems were required for transportation, storage and safe hygiene. In Waynesboro, a new era initiated a series of public works projects that continued for more than a century. These efforts would eventually cost tens of millions of dollars.

By the 1880s, Waynesboro was a thriving town with nearly 5000 residents. Not only did its townspeople use water for personal use and agriculture, but new firefighting units needed a handy supply to douse fires. Local industry also required plentiful water to power growing enterprises.

The first fire engine appeared on Waynesboro’s streets in 1879. Industry titans Frick Company and Geiser Manufacturing had launched their businesses a few years earlier, and others like Landis Machine Company would soon follow. The town would eventually become an industrial powerhouse. The Waynesboro Water Company was chartered on July 11, 1882. Fittingly, the community’s first foray into water as a stand-alone industry occurred during an important local development period.

Waynesboro’s first water investors were not only Borough residents; other backers came from Philadelphia. The Waynesboro Water Company eventually issued 12,000 shares of stock. This new enterprise went to work quickly, laying seven miles of pipe in town and the countryside, with diameters ranging from 4 to 12 inches. The American Construction Company of Philadelphia was the project’s contractor.

Insufficient water pressure was a transport problem. So, a pumping station was built at Hopewell Mills, three miles from Waynesboro. Locomotive boilers made by Geiser Manufacturing powered those pumps, which propelled water toward town at 500 gallons per minute.

In 1883, a new reservoir was built atop a Mt. Airy Avenue hill, holding a 1.4 million gallon capacity. This storage basin was 140 feet above Waynesboro’s town square, or equal to the pinnacle of the Trinity Church spire. That height differential was crucial. Gravity was a water system’s best friend.

A local newspaper article from that period described the process involved in transporting mountain water into town and storing it there. “Water passes through several screens and is filtered before discharging into the reservoir. No possible contamination can pollute the water which is absolutely pure.”

As Waynesboro prospered, new water transmission lines were extended to the Old Forge area in 1900. This allowed the developing water system to tap into Rattlesnake Run, Swift Run and East Branch of Antietam Creek’s waters, to add to the original water source at Bailey Spring. A rustic caretaker’s house was built at Old Forge in 1914. The Water Company paid their laborers the standard wage for that time: 11 cents per hour.

A few years later, at the brink of World War I, Waynesboro residents scratched their heads at the varying rates offered by their local water provider. The Leland Hotel– later the Anthony Wayne Hotel — was charged $50 per year for water usage. But the Central Hotel (now known as the White Swan building) paid only $38.50 for its annual water bill. Multi-family residential houses often paid the same fee as single-family homes.

In 1920, the Borough of Waynesboro inquired about purchasing the privately owned Waynesboro Water Company. That business claimed its enterprise was worth $420,000. The Waynesboro Town Council, led by President J.W. Crest, estimated the company was valued at $224,000. On July 1, 1922, during a meeting at the Wayne Building, the two parties met in the middle. The Borough of Waynesboro became the water system’s new owner for $330,000. The sellers, 200 former stockholders, who held between 1 and 400 shares, received $27.50 per share.

Another building phase commenced soon afterward. A new reservoir, holding 5 million gallons, was built at Old Forge in 1928. The next year, the aging Mt. Airy reservoir was replaced by an upgraded Waynesboro basin, this one with over twice the storage capacity (3.5 million gallons), and it was located on N. Broad Street. The combined price tag for these infrastructure improvements totaled $99,340.

These projects were sufficient to float Waynesboro through World War II, but in the post-war age, more improvements were necessary. The town needed to upgrade its water resume. Once again, community leaders dove into action.

The Borough Authority was created in November 1951 for an ambitious purpose: to construct a gigantic Antietam Impounding Dam in the Appalachian Mountains. The targeted property encompassed 1,100 acres and was located in Adams County. With earthen walls that retained an impressive 150 million gallons of water, the new reservoir cost $520,000 when completed in 1952. Heavy rains that year quickly filled the once-empty basin to the brim, eight months ahead of schedule.

After this significant achievement, the Borough Authority didn’t rest on its laurels. A standpipe and pumping station was built in 1968, and the original Old Forge Treatment Plant was constructed in 1974. This latter project treated 3 million gallons of water per day. In 1978, the existing in-town reservoir was replaced by a mammoth above-ground green water tank that held 3.5 million gallons. The old reservoir was eventually filled in.

A new leader emerged for Waynesboro’s water system in 1979: Jon Fleagle. A U.S. Army veteran and Penn State University graduate, Fleagle is also a licensed Pennsylvania engineer, which certifies him to oversee projects within the municipal water industry. Under Fleagle’s guidance, Waynesboro’s water system has continued its innovation and growth. Fleagle also serves as a Waynesboro Ward 2 Borough Councilman and is a board member at the Industrial Museum.

A second Old Forge Water Treatment Plant was built in 1993. This $7 million project now treats 4 million gallons per day. A backup Waynesboro water source, Well Number 2, was tapped in 2009, generating 250 gallons per minute and costing $2.6 million.

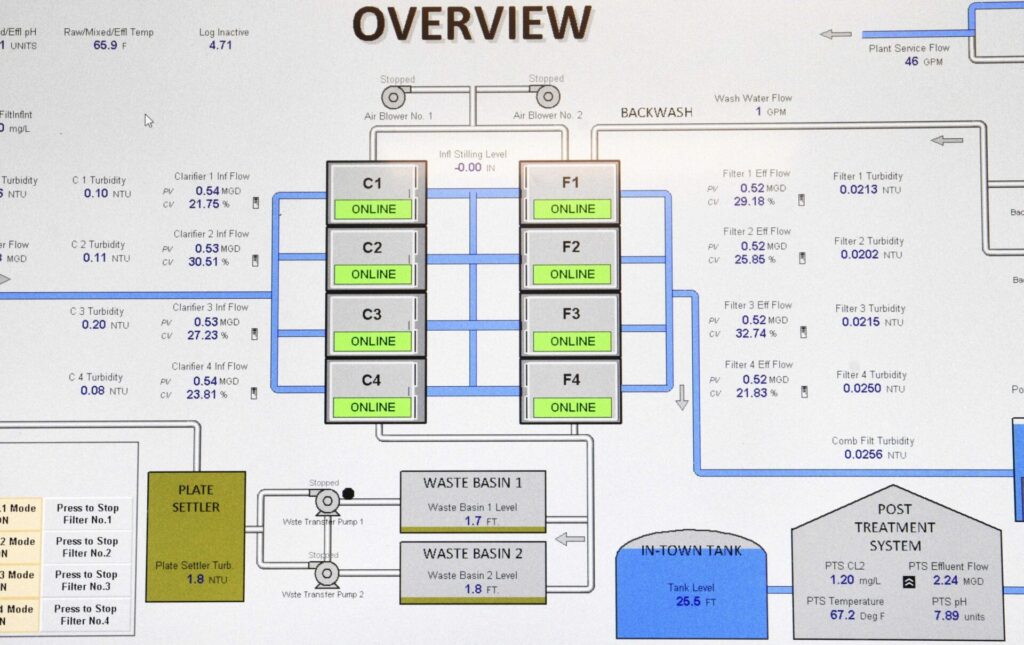

A visit to the current Old Forge Treatment Plant is an education in chemistry and diligence. Like most modern facilities, this plant is computerized and automated, but the dedicated round-the-clock staff carefully watches all control-panel gauges and related metrics and can take over manual control of the plant at any moment necessary.

The plant’s personnel supervises all additions and subtractions made during the treatment process. They monitor alkalinity, hardness, color and turbidity, among many other qualities. Raw intake water is filtered on a microscopic level, using four clarifiers and four large filters. This finely tuned equipment assures the finished product attains drinking water safety standards well beyond what is lawfully required. By conforming to this high level of quality, every Waynesboro citizen should be thankful.

Today, Waynesboro uses 1.4 million gallons of water daily. With a 4 million-gallon-per-day treatment capacity flowing into 101 miles of pipe. With 150 million gallons of water banked in a scenic reservoir for a not-so-rainy-day, the water system’s 8,100 customers enjoy reliable service and protection from drought.

After 45 years in the water industry, and as current Borough Authority Chairman, Fleagle is justifiably proud of the system’s achievements. “We just refurbished the Old Forge plant in the past six months,” Fleagle said. “We replaced the filters and upgraded the computer systems.” This recent project cost $5 million. An emergency spillway is also in the planning stages for the Antietam Impoundment Dam, as the Waynesboro water system continues to invest in the community’s future.

In a 1970s newspaper column, celebrated writer and historian Wib Davis lauded Waynesboro’s drinking water. He said, with obvious hometown pride, that the community enjoyed “the finest water in the world.” Considering its pure source of Appalachian rainwater and the local water system’s history of innovation and excellence, a reasonable conclusion is that Wib was right. Flowing daily like a liquid breath of fresh air, Waynesboro’s water is the elixir of life.