When I was a youngster, on most weekends after church our family visited my maternal grandfather, Bob. At the time, he was in his 70s and his health was in decline. But his spirits were typically upbeat, especially when his rambunctious grandkids, clothed in Sunday best, jumped into his bed.

Each week at Grandad’s house, I would sidle up to him and say, “Tell me about the good ol’ days.” He would smile and entertain us with his tales. Born in 1900, Bob witnessed many historic events during his 20th-century life. The automobile became a growing trend, chugging along Waynesboro’s dusty streets, and he marveled at the first airplanes cruising across the sky.

Luckily, Bob was too young to serve in World War I, but his only son and namesake, Charles Robert Brezler, joined the navy during the Second World War. He traveled the seas on a mine sweeper and returned home safely. Bob’s youngest daughter, Georgia, became a Catholic nun, and she too traveled to foreign lands in service to her faith. Of course, we always enjoyed Grandfather’s stories about his daughter Peg’s childhood; she was our sweet mom.

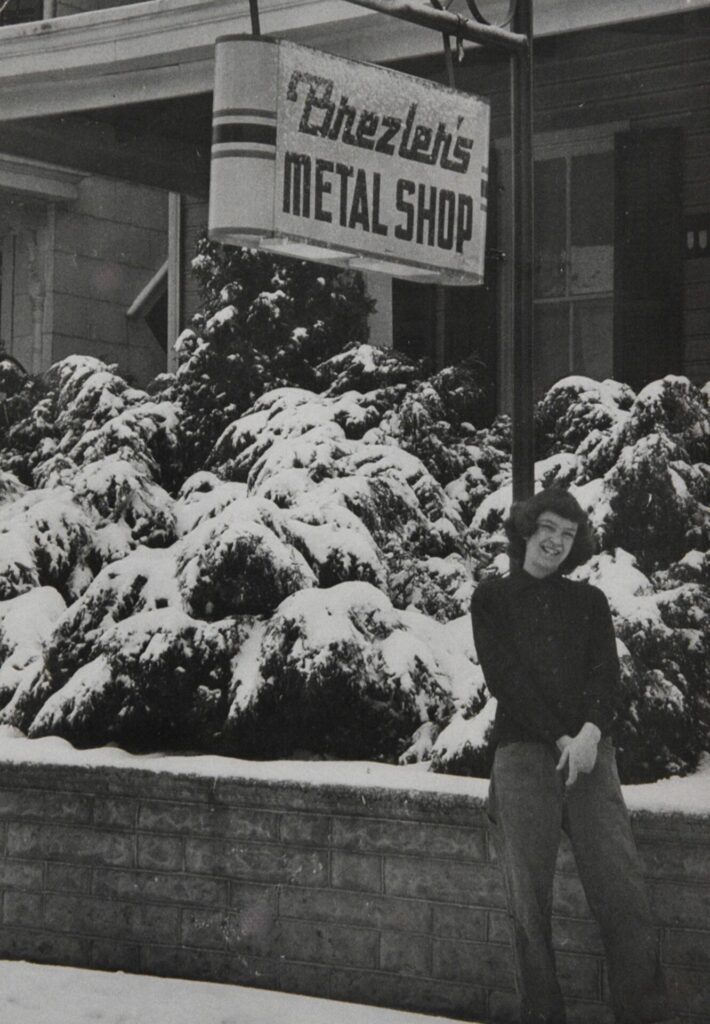

In between world wars, Bob guided his family through the Great Depression. He traveled to the Virginia Naval yards to find work. His wife and five children remained in Waynesboro, and hungry people who appeared at their front door were never turned away — always offered a home-cooked meal. In the following years, Bob started his own business, a metal shop. Later, his son and son-in-law joined this thriving family enterprise. When he retired after decades of hard work, Bob finally bought his dream car: a Cadillac. In retirement, he retained his zest for life. Bob was thrilled when the first man walked on the moon.

I was named to honor my grandfather, even though my first name was his middle one. When I knew him, Bob was a widower. His cherished wife, Teresa, had passed away several years earlier on St. Patrick’s Day, and fittingly, her maiden name was Murphy. Bob’s eyes always sparkled when he talked about her. My mother told me that Teresa and I were once great friends. But I was 3 when she died, and I couldn’t recall a single mental image of my grandmother.

Maybe my longing to remember Grandma Teresa sparked a lifelong quest. To this day, I enjoy learning about family members and people obscured by my faulty memory, or about events before my lifetime.

During my childhood, I became interested in other people’s pasts too. Growing up close to Washington, D.C., and in between Gettysburg and Antietam, it was easy to be drawn to the intricate sketch of American history. My first love in this genre was U.S. presidents, dignified men who rose to the pinnacle of American political power.

Abraham Lincoln was commonly worshipped, and rightly so. With his famous address at Gettysburg (many school kids memorized all 272 words), and his bearded profile stamped on pennies and immortalized on $5 bills, Honest Abe was an American icon. Our school took a field trip to Washington, D.C., and we were awed by the Lincoln Memorial, a white-columned temple built for a hero.

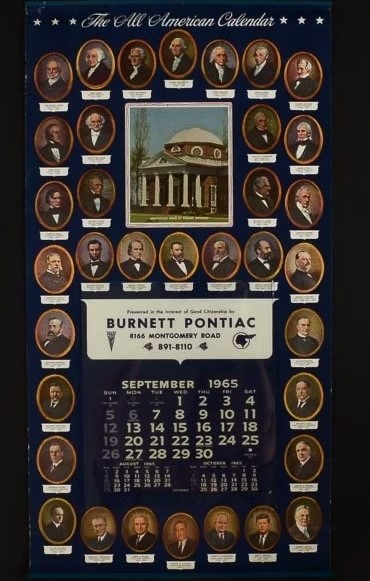

But I wanted to study obscure presidents too, and one summer I discovered the perfect teaching aid. I noticed a calendar at a friend’s house. It was unlike any other I’d ever seen, a gigantic vertical wall hanging, almost four-feet long. On a patriotic deep-blue background, the portraits of each American president were portrayed within a fancy gilded frame. Those floating faces were stylishly arranged around a central calendar layout.

LBJ was the acting 36th President back then. He was the last leader featured bottom right, while George Washington stared with indifference at top left. In my 8-year-old eyes, that calendar was a priceless work of art.

“Where did you find that?” I asked my friend. “My Dad bought a new car at the Pontiac dealer,” he said. “They gave it to him.”

My parents weren’t looking for a new car, but I wanted that calendar. My mom suggested I visit the dealer; maybe they would sell me one. Walking alone into the Potomac Street showroom, I asked how much the president’s calendars cost. A suited salesman looked at me like I was from Jupiter. “They’re only for customers,” he said.

I wasn’t a pushy kid, but told him how much I liked the presidents. A few minutes later, I was still politely hanging around the showroom, studying the presidential calendar displayed on their wall. That same sales guy returned with a half-smile. He carried a giant rolled-up calendar secured by a thick rubber band. “How much?” I asked. “No charge, kid,” he said. “Scram” was likely what he was thinking.

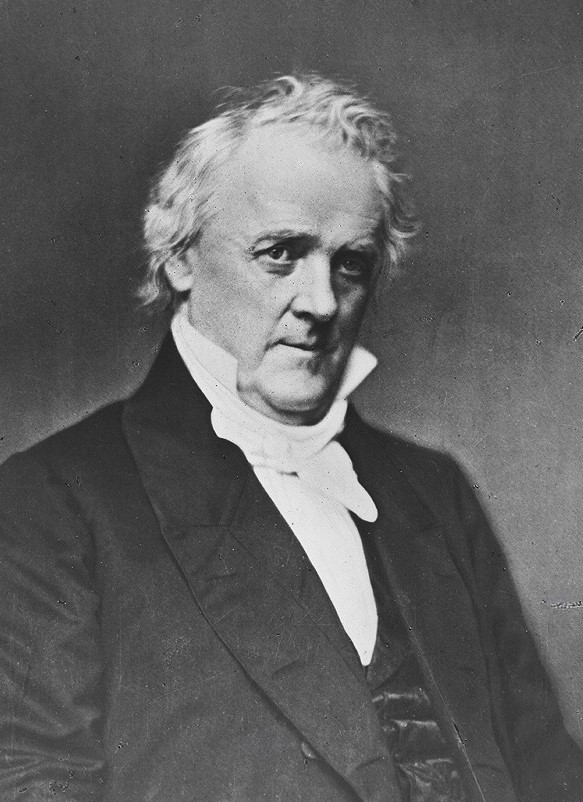

A few weeks later, I could recite all the presidents in order inside my head. For reasons later learned, little was said locally about Franklin County’s contribution to this revered hall of presidents. His name was James Buchanan, born near Mercersburg. His cocked head and handsome features were seen in the middle calendar section, next to Lincoln’s stoic face.

Growing up in a big family, it was a tight squeeze in our station wagon (four boys/three girls), so trips to local historic sites were rare. My aunt and uncle lived in Gettysburg with our five cousins, and we traveled for visits there a few times each year. But our trips to Gettysburg were quick affairs, with no time set aside for a side excursion to the famous battlefield.

My parent’s tight schedule suggested, “It will always be there. You’ll have plenty of time to explore the battlefield.” Those gleaming monuments and imposing cannons would have to wait.

Later, as an adult, I met people who lived in places rich with history — like Gettysburg — or in cities such as Savannah, Philadelphia or Washington, D.C. When I asked for their opinion about a famous site, one they surely grew up visiting multiple times, they often said: “I’ve always wanted to see that place but haven’t gotten around to it yet.” When citizens lived in the center of a splendid place, be it historic, scenic or just plain interesting, it seemed their mindset often mimicked my parents priorities. It’s local. No rush.

I attempted to reverse that trend when I moved as an adult to Atlanta. The South was a unique cultural region, home of former rebels and other interesting characters, real and imagined. Celebrated books, some turned into epic movies like Gone With The Wind, lavishly praised the antebellum agrarian society — with major faults smoothed over — creating a mythical version of Dixieland.

I soaked up the Georgia heritage sites, feeding my curiosity for people and places that created that Deep South mystique. I also wanted to learn about my new home and how intangible factors helped Atlanta (destroyed during the Civil War) evolve into a modern city. I relished these Southern experiences, since I grew up a Yankee. Like most history lovers, the unfamiliar was always more intriguing than the familiar.

But during this period, when I came home for Pennsylvania visits, I was occasionally on the receiving end of those questions about a local landmark and provided the same familiar answer. A visiting friend asked “What’s the best place to explore first on the Gettysburg battlefield?” At the time, I couldn’t offer many educated suggestions. “You like presidents, I’m sure you’ve done the White House tour. What’s the Oval Office like?” Sorry, I hadn’t been there yet. “Have you seen the famous building where John Brown got captured at Harpers Ferry?” Nope, been meaning to see that too.

Many years later, I returned to live along the Mason-Dixon Line again. Since commercial photography had been my career, I already learned a visual lesson about my hometown area, a fact unappreciated in my childhood. The Cumberland Valley was truly a picturesque place.

But after being gone so long — nearly four decades — I required a refresher course on the area’s historic treasures. The best way to re-school myself: venture out and experience local history. I explored sites I’d previously put off visiting, previously thinking plenty of sifting sand remained in my human hourglass. Fortunately, most of the historic gemstones on my bucket list survived, preserved by wise organizations, towns, governments and visionary people.

Sadly, I also discovered other worthy places had faded into extinction. Development was a prime culprit. Others sites were now practically off-limits, like the majestic White House, which after terrorist attacks required congressional approval to secure a personal visit.

The first lesson learned is don’t wait. Go experience these wonderful places while they’re still funded, available or even exist. They’re nearby and easily located. A local historic site is just as riveting as others in far-off states. Sometimes these area gems are far more fascinating, like finding buried treasure in the back yard.

Remembering my grandfather, the second lesson learned is bittersweet. Stories should be written down, or better still, taped or filmed. I wish our family had practiced that tradition, not only to recall the exact phrasing of these stories, but to hear the speaker’s cadence, or to visually witness the storyteller’s personality and physical qualities. I was only 14 when Bob passed, and he was my last surviving grandparent. Sadly, some of my younger siblings have no living memories attached to any of their grandparents.

History enriches our lives because its lessons transcend memorized calendar dates or reciting poetic lines from a famous speech. History is created by people, not by events. History is found in stories told by a dear old granddad, in a treasured black-and-white photograph of a lovely grandmother who once lived and loved, and through childhood exploits that sparked lifelong interests. These experiences are unique to each of us and normally kept close to the heart. But they should be shared. They add detail and texture to our personal and family stories, told in tiny chapters. Bound together, they create a larger historic volume, that when passed forward, will never go out of print.