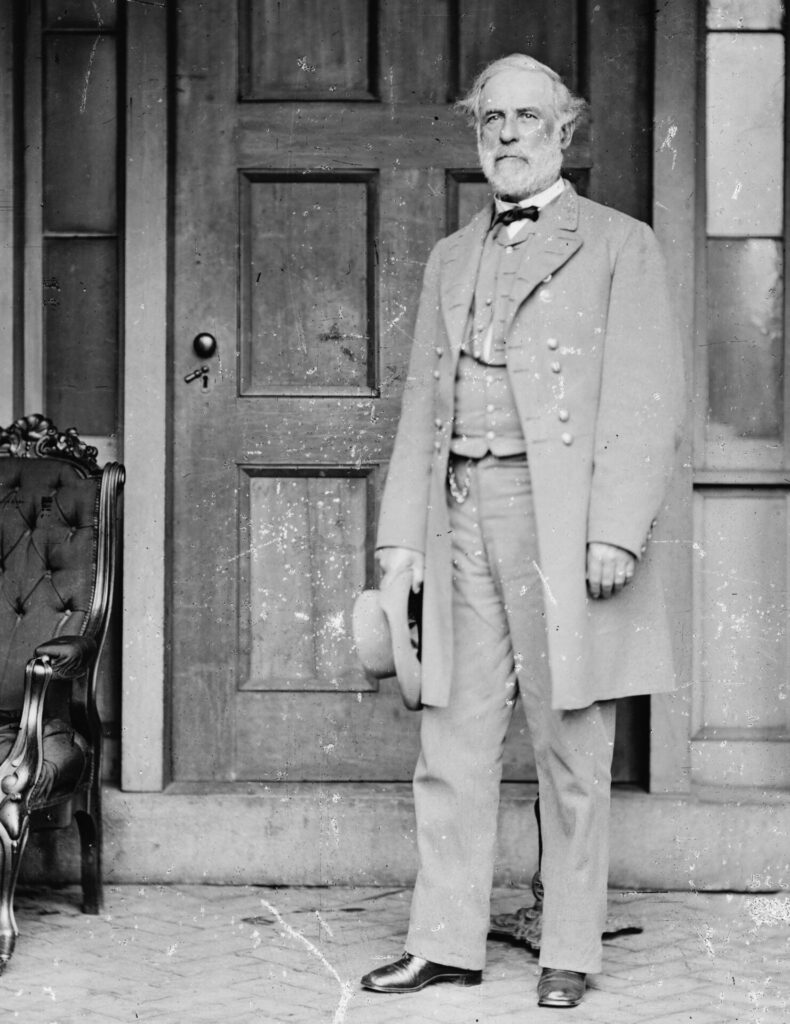

On July 4th, 1863, 50,000 defeated Confederate soldiers under General Robert E. Lee’s command initiated a complex escape route from Gettysburg. Union forces would nip at their heels as rebel columns retreated from the battlefield with wagon trains that measured a combined 60 miles long.

161 years later, a spirited group of Confederate reenactors restaged a portion of that tumultuous retreat, named “Thunder and Mud”, by marching eight miles from Fairfield to Monterey Pass. Their biggest challenge on July 6, 2024 wasn’t bolts of lightning or muddy roads (or a chasing army firing at them), but they battled oppressive heat of a modern July day instead, all while marching uphill wearing wool uniforms and shouldering old-time rucksacks.

This reenactment instigated a closer look at Lee’s epic retreat and its impact on local and national history, including the chaotic battle at Monterey Pass.

During the Civil War, Lee made a calculated gamble when he invaded the north in June, 1863. This daring was a trademark of the unpredictable southern General, a trait that previously paid off with a string of brilliant victories. But some historians believe Lee overestimated his soldiers at Gettysburg, and that misplaced confidence may have sealed his defeat there. After that epic battle, Lee needed a well-orchestrated plan to ensure his army would survive.

The logistics of the Gettysburg Confederate retreat were staggering. With a massive army traveling through enemy territory, the rebels had to feed and supply tens of thousands of men while in constant movement, foraging for every scrap of food they could scavenge from the Pennsylvania countryside. They herded cattle, hogs, sheep, and carried countless other food rations. Also stowed in retreating wagons were supplies to wage war, including ammunition, which after Gettysburg was in short supply. All told, moving that much men and material after a devastating battle loss was an incredibly challenging and dangerous mission.

Another major liability: the Confederates ferried many wounded soldiers along, and they suffered riding on springless wagons, jostled on rough dirt roads leading out of Gettysburg. Primative local roadways rarely provided a smooth track but were made nearly impassible in July 1863 after heavy downpours and damaging wagon traffic.

With so many miles of men and material, one route couldn’t provide sufficient space for travel. Lee split his army in two. The first column traveled northwest toward Cashtown, while the second headed southwest toward Monterey Pass. The goal: reach the Potomac River on the western side of South Mountain as quickly as possible, and then cross into the safety of Lee’s native Virginia.

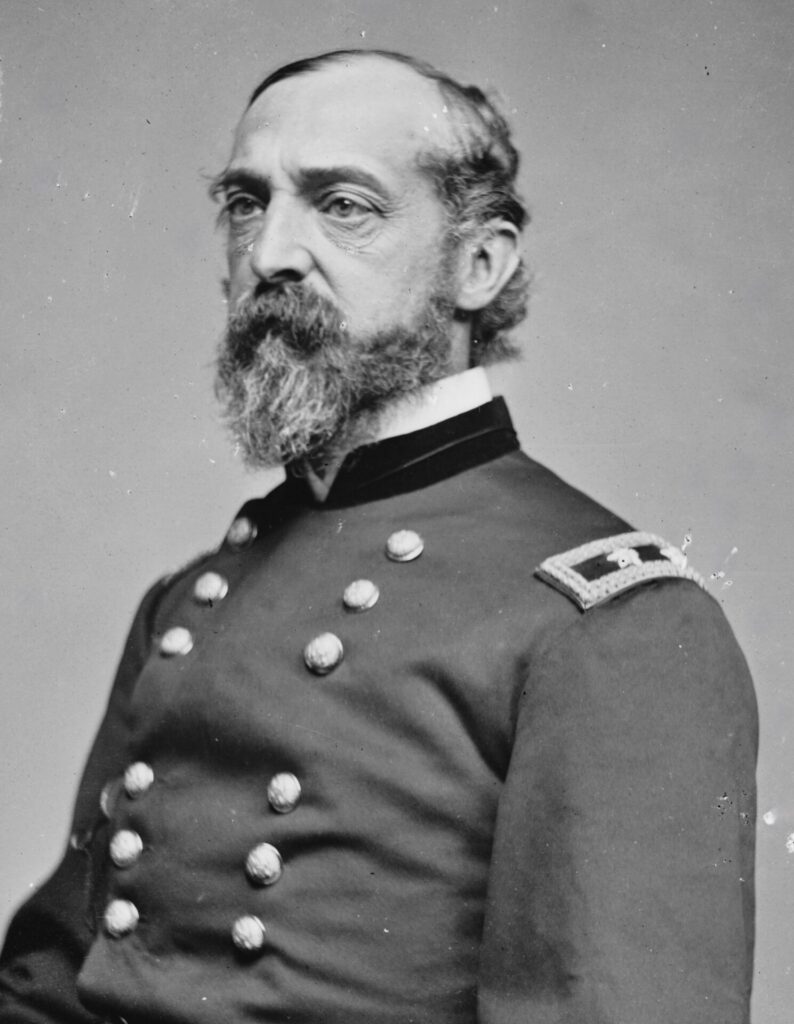

The Union Army was commanded by General George Meade. At the time, he was the latest military leader in a long line of Generals appointed by President Lincoln. As the Gettysburg battle commenced, Meade had been in charge for only three days. Despite suffering over 23,000 casualties, Meade was still victorious at Gettysburg, since Lee lost even more men during the Civil War’s bloodiest battle.

As Lee started his retreat, Meade took a cautious approach. The Union commander wasn’t sure of Lee’s intentions. Did the crafty southern General plan to fortify the mountain passes, entrench, and challenge Meade to another major battle? Or was Lee simply escaping back into southern territory? Meade’s mission was protecting the cities of Baltimore and Washington from attack and forcing Lee out of northern territory. Uncertain, Meade waited for a day, then asked his men to pursue Lee’s long wagon train to clarify the Confederates’ movements.

As the chase began, Union cavalry and other regiments harassed the Confederates’ southern column on their march toward Fairfield. Several skirmishes erupted as southerners valiantly protected vital supplies and their wounded men. All along the route, at places like Black Horse Tavern and the Weickert Farm, local properties became Confederate military hospitals due to a monstrous number of Gettysburg casualties. At several locations, southerners were buried in a pasture or yard. Years later, some remains were reinterred and moved south, to rest forever in hometown graves in North Carolina and Georgia.

When the wagon train reached Fairfield, a Civil War traffic jam formed and nearly ground movement to a halt, leaving the Confederates vulnerable. Federals lobbed shells into town, as local citizens ran for cover. At this juncture, historians recall fascinating stories of civilians caught in war’s maelstrom. One couple, the McCreary’s, sheltered in their Fairfield basement as cannonballs flew. There, during this frenzied Confederate retreat, the couple’s first son was born, and his christened middle name honored Union General “Uncle John” Sedgwick, who commanded a nearby unit.

With cannon fire serving as proper forward motivation, the massive Confederate column of General Richard Ewell finally snaked out of Fairfield and headed uphill toward Monterey Pass. Heavy rain pelted the escaping army and turned mountain roads into a quagmire.

Riding from Emmitsburg, MD, Union Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick, with his comrade Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer, raced with the calvary toward Monterey Pass, hoping to cut off the Confederate retreat. They arrived after dark, during a violent thunderstorm. During the late hours of July 4th, and into the early morning of the 5th, a dramatic nighttime Civil War battle raged around Monterey Pass. The fate of the Confederate retreat and the southerners’ ultimate survival hung in the balance.

Saturday’s Thunder and Mud event re-lived a portion of these chaotic events through a contemporary lens. A group of Virginians began their march at 7 am and strived for an authentic war-time experience. As they departed Fairfield, the camel-hump of Jack’s Mountain still marked the southern horizon. Like real Confederates 16 decades earlier, these reenactors carried everything on their backs, without benefit of breathable clothing or light-weight accoutrements. They contended with dangerous weather too, as temperatures climbed into the mid-90s with stifling humidity. At a mid-point of their modern-day journey, the Confederates stopped and waded into a rural stream, experiencing a bygone moment of cooling relief.

At the conclusion of their march, the reenactors entered Monterey Pass Battlefield via Maria Furnace Road. That road, once a prominent thoroughfare through the pass, is now a tree-lined and unpaved lane through an Appalachian woodland. The Confederates tramped in tight formation, with one soldier out front scouting forward, while several other men roamed the woods to each side, searching for phantom Union enemies. As the men appeared in the woods, the experience transported battlefield visitors into the past, back to a historic July 1863 day when the Confederate army’s fate was yet undecided.

Later, the reenactors were pleased their march was over. A handsome, red-bearded leader named Franklin Van Valkenburg spoke for the group. “We do these reenactments to educate the public, but today our unit gained a greater personal appreciation for what those men went through during the Gettysburg retreat.” While there were few surprises during Saturday’s march, he remarked about his comrades’ stamina. “I’m proud how our men endured the heat and kept moving forward,” Van Valkenburg said.

Friends of Monterey Pass Chairman Lee Royer was present to welcome the reenactors and praised their efforts. As the Confederates gathered near the museum and were reviewed one last time before disbanding to waiting tents, a crowd applauded the tired men. A group of Federal reenactors stood to the side, near a smoking campfire, and nodded their appreciation. They interpreted cultural and military aspects of camp life all morning and afternoon. With much easier duty on this day, the blue-coated Yanks were likely thankful to miss the broiling uphill retreat reenacted by the Confederates.

Thunder and Mud was a symbolic recreation of a major Civil War event- since the group traveled without livestock, a wagon train of wounded comrades, or a chasing army- but the event stirred interest and appreciation for the complicated logistics that marked the Gettysburg retreat. This living history reenactment fostered greater understanding of the Monterey Pass story and its ties to Lee’s dramatic Gettysburg withdrawal. Thunder and Mud reenactors also raised a generous $1500 donation for the park.

Back in 1863, as the Monterey Pass battle concluded, Kilpatrick, Custer, and their men failed to halt Lee’s retreat. They disrupted and harassed it by capturing almost 1500 Confederates and burning/commandeering many wagons. The battle also spilled over into neighboring Maryland territory, making it the only Civil War contest fought on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line.

But Lee’s escape plan eventually succeeded. Many have wondered if Union General Meade was too timid in his pursuit. Could he have destroyed Lee’s army before they crossed the Potomac and ended the war in 1863? That is a fascinating topic of unanswerable speculation. In reality, the Civil War raged for another 21 months after Monterey Pass.

Surprisingly, a smaller portion of Lee’s army returned to Pennsylvania a year later. On July 30, 1864, a unit under General Jubal Early’s command burned Chambersburg, after a ransom demand went unpaid. Another Confederate retreat followed, but this time, the Union army seemingly went after invading Confederates with greater vengeance, since civilians suffered the brunt of damage from that catastrophic southern return to northern territory.

Today, Gettysburg’s epic battle commands the most nationwide and worldwide attention. But Monterey Pass also possesses many stories to enlighten history lovers, encapsulated in gorgeous grounds, a first-rate museum, and a series of hosted events. The Friends of Monterey Pass continue an ambitious agenda to improve the park and share its important heritage. This mountaintop battlefield, located in Washington Township at 14325 Buchanan Trail East, Waynesboro, (near Blue Ridge Summit) is a must-see destination on any Civil War enthusiast’s or local history fan’s wish list. To learn more about other upcoming events, visit the website (montereypassbattlefield.org) or call 717-762-3128 for hours of operation or other general information.