Every mortal yearns to be remembered when their life eventually expires. Cemeteries evolved in American culture as resting places for the dead, but also as tangible destinations for the departed’s descendants. After reflective visitation, reminiscent tales from the living were passed down to succeeding generations. Through these stories and future visits, loved one’s histories were respected and preserved.

The permanence of gravesites was usually taken for granted. In many locations, burial grounds displayed manicured settings with fresh-cut grass, seasonal flowers, and stately monuments. Most cemeteries seemingly enjoyed entitlement to perpetual care.

But in the unfair landscape of life, discrepancies between races and economic status often followed the living into the grave. In regrettable scenarios, these inequities caused entire cemeteries to be relocated, destroyed, or simply forgotten.

On April 21, 2024, an ongoing preservation effort was celebrated for a cemetery of once-overlooked souls. The ‘Friends of Halfway African American Cemetery’ held a ribbon-cutting ceremony in Washington County, Maryland, attended by a group of descendants, volunteers, dignitaries, neighbors, and citizens.

A new cemetery entrance was officially opened. This symbolic and practical pathway promises easy access and a clearer understanding of a historic burial ground. A unique collaboration of intelligent planning and physical labor brought this event to fruition. But much work on Halfway African American Cemetery remains, as substantial legal and financial obstacles loom ahead. In addition to these challenges, a sad question persists. How could an entire cemetery be forgotten?

In the late 1800s, black Hagerstown citizens still lived in a segregated society. Although Maryland never joined the Confederacy during the Civil War, slavery was legal there until the state abolished it in November, 1864. A year later, the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed human bondage forever.

Still, some continuing racist practices in Hagerstown were overt, other tactics more symbolic. The historic Jonathan Street neighborhood thrived only a few blocks away from Summit Avenue- the same street. But the avenue changed names once it crossed north into an African American section. Then later, when Jonathan Street bisected a white neighborhood once again, it was renamed Forest Drive. Many viewed this alternate naming process as a negative stigma placed on a black community.

In 1897, a black fraternal organization called the Good Samaritans and Daughters of Samaria founded a cemetery. It is thought the local African American church, the Bethel/Ebenezer AME Church near Jonathan Street, ran out of space in its graveyard and the Health Department forbid further burials. The Good Samaritans purchased six acres of farmland in the Halfway community, near a Jewish cemetery. This then-rural location was three miles from Hagerstown’s center and ‘halfway’ between the Hub City and Williamsport.

Burials continued at the Halfway African American Cemetery (HAAC) until 1932. Later research found approximately 400 black citizens were interred there, including fifteen veterans. One man thought to be buried at HAAC was named Perry Moxley, a prominent Hagerstown African American citizen and a leader during the cemetery’s founding. In life he led a group called Moxley’s Band, a black musical group founded in 1854 and later part of the First Brigade of U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War.

It is unknown why HAAC burials ceased in 1932. But research suggests the Good Samaritan’s suffered financial difficulty. In 1944, the group sold their Halfway property- except for .7 acres- which remained a designated cemetery. Later, houses were built on the larger sold tract- but it is also unknown whether headstones were moved or any remains re-interred from original gravesites.

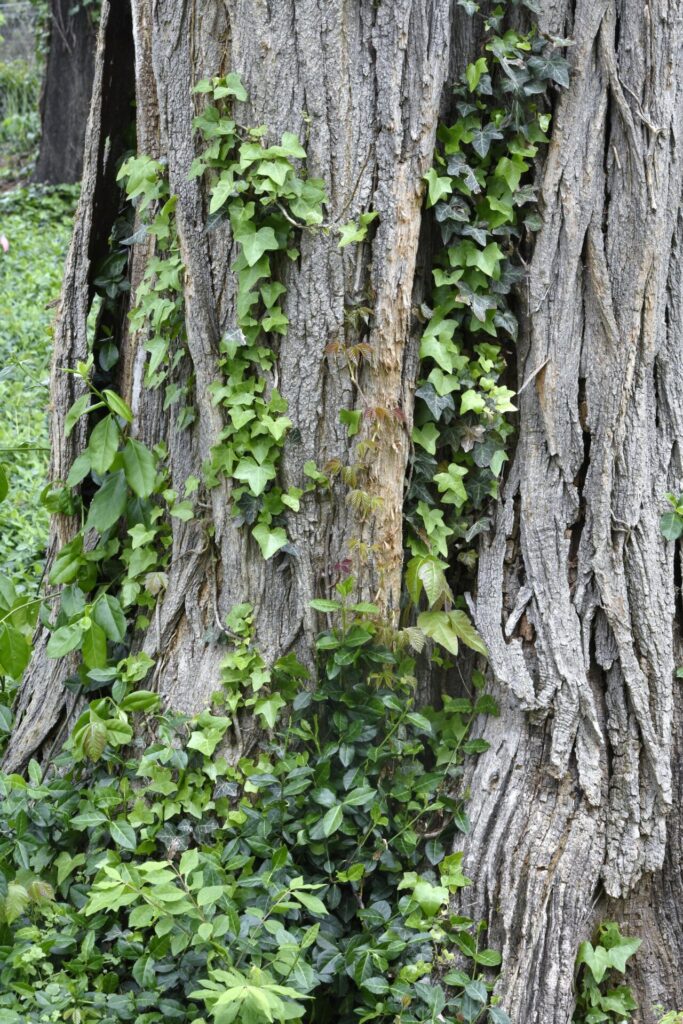

In time, a new neighborhood surrounded the remaining cemetery. Fenced yards on now private property caused the African American Cemetery to become an isolated island. Without public access, the cemetery was eventually reclaimed by nature. Large trees fell, damaging headstones. The burial lot became an overgrown jungle choked by an impenetrable tangle of weeds. For more than a half-century the cemetery sat ignored and neglected.

Sadly, the process that led to HAAC’s deterioration occurred at other African American cemeteries in Maryland and elsewhere. In some cases, entire cemeteries were lost or paved over, victims of urban sprawl or commercial development. Eventually, some zoning laws were strengthened, but not in time to save many sites. In 2023, Congress passed the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act, seeking restorative justice.

Back in 2007, Elizabeth Paul moved into a house located on the old Halfway burial grounds. The surviving cemetery abutted her property, but she was initially told graves and headstones had been moved. When she noticed other community members were disrespecting the overgrown lot, she researched county records and found the cemetery still existed, owned by the Good Samaritans.

Afterward, Paul started a process that ultimately became the organization ‘Friends of Halfway African American Cemetery’. Over a period of years, Elizabeth utilized her career experiences to form a core group of experts and impassioned community leaders, leading a path toward HAAC restoration.

In 2017, Paul connected with Emilie Amt, an emeritus Professor of History at Hood College, award-winning author, and leading scholar on African American studies in Western Maryland. Together, the duo formed a non-profit entity to attract grant money and other valuable resources to their HAAC cause.

In the spring of 2020, the first cemetery cleanup was organized. Large trees needed removed and a local tree service donated their equipment and expertise. One problem emerged: the narrow fencing gap in Elizabeth’s yard wasn’t wide enough to allow vehicles to enter the cemetery. She had the fence moved and came up with a new plan. Paul decided to donate a portion of her property to serve as a public cemetery entrance. That new pathway was celebrated on April 21st.

As the ‘Friends’ organization grew, a Board of Directors formed, made up of collection of experts- historians and archeologists among them. But the Friends also researched and contacted the African American cemetery’s descendants. Lola Mosby and Carolyn Brooks are two of those ancestors who joined the Friend’s Board. Both women spoke at the recent dedication and are integral members in the organization. Mosby serves as the group’s Vice President.

On dedication day, visitors experienced a renewed cemetery, seeing various tombstones discovered during the ongoing cleanup. A carpet of spring wildflowers were a reminder the natural world would always stake a claim to this property, while a trio of red tulips meant someone from the cemetery’s past had thoughtfully planted a floral tribute.

After a jubilant group cut the ribbon, historian Emilie Amt led a tour. She described the unique stories and ongoing challenges facing the cemetery’s restoration. Amt smiled when recalling how Perry Moxely’s gravestone was found during an earlier cleanup. Friends’ Board member Carolyn Brooks was a Moxley descendant.

Nearby, the tombstone of Moxley’s son was viewed, lying broken. Similar to the ongoing cemetery restoration conducted by the Friends, Moxley’s stone was pieced together, a heartbreaking tribute to a young man who once walked Hagerstown’s streets.

Amt also pointed out the grave of Ellen Fowler, whose headstone is one of the best preserved on the burial grounds. Located in a far corner of the Halfway African American Cemetery, a gracious neighbor recently moved their fencing to allow Fowler’s plot to rejoin the others. Nearby, the tilted headstone of Irving Sullivan marked the location of the World War I veteran’s remains, buried next to his father.

As the tour continued, George Roberts’ tombstone was spotted, resting against a tree. The stone was found in a nearby yard years earlier, and later offered to the Friends by a thoughtful neighbor. The sad realization that Roberts’ gravesite will never be found was further demeaned by a historical discovery: George Roberts didn’t exist. Research showed George Scott was likely the real man honored, but his stone was mistakenly etched- while his wife Ida Scott is correctly mentioned on the carving. Scott’s true name is supported by identical birth and death dates and marriage records discovered by Friends’ researchers.

Research conducted to help identity Halfway cemetery’s human remains is carried out by combing through death certificates and obituaries in vintage newspapers. The tedious work has yielded fascinating discoveries. Since the last burial at HAAC occurred nearly a century ago, burial experts believe these human remains have completely melded into the earth.

However, Ground Penetrating Radar was employed to find gravesites and give clues to the cemetery’s original layout. Most of the tombstones (about 10% of total burials) have been moved, damaged or remain missing. No records from the Samaritan’s site plan have yet been found. Elizabeth Paul also had her yard radar-scanned and grave shafts were located there as well.

Many challenges remain for the Friend’s future plans. Since they do not own the property, many grant opportunities are elusive. The group hopes to get a sponsored bill passed in the Maryland Legislature soon, to gain land ownership. Then, they will raise additional funds to restore headstones, create respectful signage, and stabilize future protection of this important property.

With public access to the cemetery now restored, the Friends invite the community to visit during daylight hours. The address is 11027 Clinton Avenue in Halfway, Maryland. The group also encourages people to join their organization, volunteer for monthly cleanups, or make donations. They can be found on Facebook (listed as ‘Friends of Halfway MD African American Cemetery). Donations can be sent to 411 Belview Avenue, Hagerstown MD 21742, or made via their GoFundMe online campaign.

Both Elizabeth Paul and Emilie Amt agree the HAAC project has been an extraordinary experience. “It’s been rewarding to help restore dignity to this place”, Paul said. These two women also believe the cemetery’s future should follow a pathway determined by its African American descendants. The Friend’s continuing mission is not only preserving this historic individual property, but also creating renewed public awareness so all cemeteries are treated with equal respect and dignity.