Along a legendary 2200-mile pathway that traces the rugged spine of an ancient mountain range, the Appalachian Trail passes through the Southern Pennsylvania/Western Maryland region. This national treasure marks its halfway point in this area, as it meanders north toward Maine, or travels south on a journey to Georgia.

The Appalachians formed over one billion years ago. When long-ago continents violently collided, rocks were thrust upward, creating a major mountain range spreading from Canada to present-day Alabama. Appalachian summits once reached jagged heights similar to the Swiss Alps. Millions of years later, natural erosion ground them down to their present rounded elevations.

At the turn of the 20th century, American civilization encroached on this vast wilderness. It was once suggested a squirrel could travel by treetops along the entire Appalachian range and never touch the ground. But by the early 1900s, logging, the Chestnut Blight, and rapid human development threatened that novel concept. Thankfully, the science of forestry developed during that same period, and wiser ecological planning soon commenced.

Benton MacKaye was the visionary who first imagined the Appalachian Trail. MacKaye was one of the nation’s first forestry professionals, born in 1879, and educated at Harvard. When MacKaye analyzed forest ecosystems in danger, he also foresaw negative impacts on human society. He believed civilizations needed a buffer that protected nature from population sprawl. In 1921, MacKaye published his theory in a work titled: “An Appalachian Trail, a Project in Regional Planning”.

MacKaye’s idea created immediate excitement and it quickly gained momentum. The Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC) was born in 1925, and work began on the ambitious trail, initially designed to link Mount Mitchell in North Carolina (the east’s tallest peak) with Sugarloaf Mountain in Maine. While MacKaye was the dreamer behind the concept, the proposed A.T. also needed a doer to help complete the mammoth task.

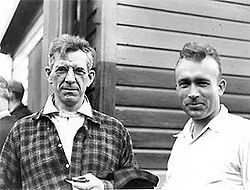

That person was Myron Avery. He came into MacKaye’s orbit and the two collaborated for a time. Avery was also a Harvard graduate, but studied law. The two men’s contrasting styles and ideals created friction. Avery was described as an intense man who enjoyed solving problems. He was always willing to compromise to accomplish big projects. By 1937, the original Appalachian Trail route was completed.

MacKaye’s heart stayed committed to the conservation movement, but he eventually split with the A.T. and Avery. Benton MacKaye later co-founded the Wilderness Society and was a lifelong outdoor champion. He lived to age 96, and while he never hiked the entire pathway he inspired, MacKaye is still considered the father of the Appalachian Trail.

Myron Avery walked a different path. He personally blazed much of the original A.T. route (today marked with 2×6 inch white blazes), and was the first person to hike it end-to-end. Avery would repeat that accomplishment several times. His high-energy and drive were well known and he served as the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club’s President. Avery then held the same title at the ATC until his death in 1952. Although he died young at age 52, Avery seemingly lived two lifetimes while conducting his non-stop trail-blazing work.

In A.T.’s early history, hikers relied solely on guile and instinct. Long before modern communications, light-weight equipment, or water-proof clothing, they carried only basic gear. During those first decades, traditions developed that endure today. The ultimate goal in early years was walking the A.T. in a single multi-month one-way hike. Called ‘thru-hikers’, these folks typically started at the Georgia southern terminus in early spring, hiked north following warmer weather, and finished in Maine by autumn.

Thru-hikers also adopted trail-name pseudonyms while signing a series of log books along their A.T. hike. Constant communication with fellow hikers was essential. Thru-hikers relied heavily on each other. Re-supply drops were shipped from home and needed picked up at trailside post offices. The entire A.T. trip required 5 million steps and little support came from the outside world.

National Geographic ran an Appalachian Trail feature in the late 1940s, and a unique woman from Ohio read it. The story inspired her. Her name: Emma ‘Grandma’ Gatewood, a mother of 11 children. In 1955, after she raised her brood, Emma decided she’d go for a hike. She rode a bus to Georgia and began her solitary journey with a shower curtain for shelter, a pair of Keds on her feet, and supplies stuffed in a homemade denim bag.

After 146 days on foot, Gatewood reached the A.T.’s northern terminus at Maine’s Mt. Kitahdin. At age 67, with boundless energy, Grandma Gatewood was the first solo woman to hike the Appalachian Trail. She would repeat that feat twice more in 1957 and 1964 (at age 76). She was the first and oldest woman to complete the A.T. three times. A hiking legend was born.

As the A.T.’s popularity grew, so did responsibilities to maintain it. The trail’s total distance changes yearly- in 2024 it logs in at 2197.4 miles. Natural issues such as erosion and flooding require constant minor route revisions to provide the safest hiking experience. A series of 31 clubs maintains the A.T’s entire route, forming a partnership that has ensured its long-term vitality.

The Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) watches over the pathway in Franklin County PA and Washington County MD sections. The PATC manages 240 miles of the A.T. (along with 650 miles of other trails) and 45 A.T. shelters. An estimated 90,000 work-hours goes into these endeavors each year. Local A.T. sections would be unsustainable without the diligent volunteer efforts of PATC’s 8,000 members.

Back in 1968, the National Trail Systems Act was enacted by Congress. This facilitated the future protection of the A.T. corridor. Today, the Appalachian National Scenic Trail travels 41 miles in Maryland and 230 miles in Pennsylvania, about 11% of its total length. 99% of the A.T. 14-state property is now owned and preserved by the National Park System.

Modern-day hikers have adopted creative techniques to enjoy the A.T in new ways. While thru-hiking remains popular, many other enthusiasts have completed the entire trail in multiple individual hikes over many years. Called ‘section-hikers’ they accomplish this within personal boundaries. Hikes are tailored in length and direction, based on fitness level, difficulty, or seasonal weather conditions. Other hikers ‘flip-flop’ by starting at local spots like Harpers Ferry and walk south- then return later to walk north toward Maine.

Peggy Weller is a local section-hiker who completed the Appalachian Trail. Weller, a retired teacher at PSU Mont Alto, yearned to test her capabilities. She said the hardest sections of the A.T. were an “exquisite obstacle course”, but over five years, she chipped away at A.T. trail sections. Finally, Weller, who gave herself the trail-name ‘Nanny Goat’, finished her quest in 2016. “The trail teaches you’re much more resilient than you think you are.” When she completed the journey, Weller was 68 years young. Today at 76, she still walks regularly and organizes a hiking group.

On Earth Day 2014, Waynesboro became an official Appalachian Trail Community. This distinction is earned by a formalized commitment to help passing hikers. Often, local A.T. Community organizers give free rides to local grocery stores or hotels. Some even bring A.T. thru-hikers home and provide a hot shower, hearty meal, or access to a washer/dryer. This extra kindness from strangers is known throughout the hiking community as ‘trail magic’, which often materializes when a hiker needs it most.

For outdoor enthusiasts, the Appalachian Trail is a pathway to solitude or a scenic avenue to re-connect with nature. Fortunately, many accessible A.T. trailheads are found locally. The A.T. is open to hikers of all ages and abilities- regardless if the goal is five million steps or five thousand. Over three million people enjoy the A.T. every year.

In spring, before trees leaf out, a profusion of wildflowers are found along the Appalachian Trail. These discoveries are tiny gifts, showcasing a small portion of the vast diversity of flora and fauna found along the Appalachian Mountain range.

To learn more about the A.T., visit the Appalachian Trail Conservancy website: appalachiantrail.org. The Appalachian Trail Museum in nearby Pine Grove Furnace celebrates the A.T.’s rich history in a rustic rock barn (atmuseum.org). Every year, a new class is inducted into their A.T. Hall of Fame. Charter members include Benton MacKaye and Myron Avery. Grandma Gatewood is another well-deserved inductee.

A local event, the upcoming Appalachian Trail Outdoor Fest, is scheduled at Red Run Park on Saturday June 8th from 10-4.

The Appalachian Trail is a unique American concept, and fits perfectly into the National Park System. Now within sight of its centennial, the A.T. is a celebrated ribbon of wilderness that inspires hikers to mimic the ancient Appalachians- to age gracefully with elegance and simplicity.