Cold Spring Park still inspires vivid memories. For most of the 20th century, this charming Waynesboro park mirrored the evolution of how society traveled, gathered, and played. Unique traditions developed during 80 enjoyable years. These customs were inspired not only by a trolley company and a dedicated family of local ownership, but also by the social graces and joyful fads of revelers who flocked there year after year.

On February 10th, Cold Spring’s fun and fellowship were remembered through a pleasant story-telling session at the Waynesboro Historical Society. Forty years after the park’s closure, the Oller House hosted event re-lived Cold Spring’s glory days. Barry Tucker served as the main presenter, and shared family stories and a treasure trove of artifacts from his personal collection. Cindy Burger Knauer was also present, granddaughter of Cold Spring Park’s former owner. Together, they sparked affectionate reminisces among a large group of attendees.

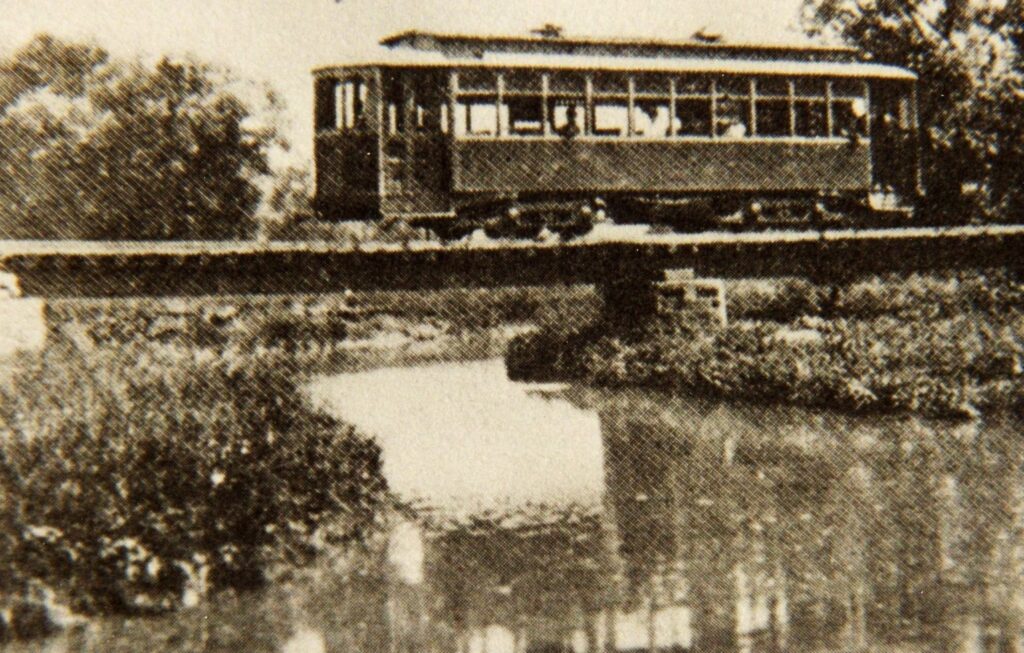

Cold Spring Park was the brainchild of the Chambersburg, Greencastle, and Waynesboro (CG& W) Railway. Like another famous local gathering spot, Pen Mar Park, Cold Springs was created as a tourist destination by a transportation company. Pen Mar’s guests traveled to that venue by the park owner’s locomotion, the Western Maryland Railway. Cold Spring’s guests arrived, in its first years, by CG&W trolley.

CG&W Railway originally formed to ferry passengers between their three namesake towns. The automobile era was still several future decades down the road. To fill more seats, the trolley company purchased 24 acres of low-lying ground just west of Waynesboro, situated on the West Branch of Antietam Creek.

Naming their new tourism enterprise Cold Spring Meadow Park in 1904 was a no-brainer, a chilled spring on the property served as inspiration. Their business plan worked to perfection. Locals packed CG&W trolleys to Cold Spring and the park’s popularity was instantaneous.

Cold Spring’s attractions and amenities grew yearly. At first, its natural setting was the main draw, as visitors escaped summer heat by wading in refreshing cool waters. A large open pavilion was added soon after, and a new musical group performed regular concerts. Their name: The Wayne Band. This iconic brass band formed in 1899 and still draws crowds today, 125 years later. During early years, Cold Spring Park hosted family reunions, company picnics, and church socials. Those gathering traditions would continue for the park’s entire duration.

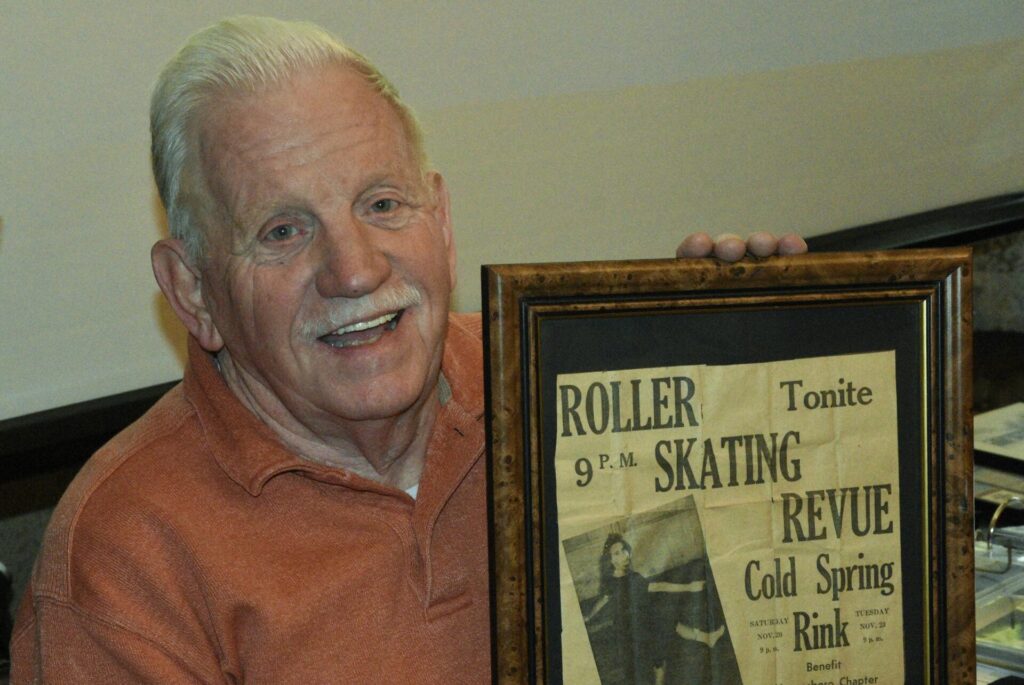

WHS Presenter Barry Tucker’s face warmed when he reminisced about his family’s adventures. “Cold Spring Park was a great source of happiness and pleasure. As kids, we couldn’t wait to go there.” Tucker said the park’s name was well-chosen. “That creek was frigid. My brother and I played in the water until our feet turned blue.” Tucker also shared memorabilia he’d collected over the years. He plans to one day donate those artifacts to the Waynesboro Historical Society.

As Cold Spring Park gained increased popularity, the trolley era slowly came to an end. CG&W suffered a major calamity in 1916 when their Waynesboro trolley barn caught fire. They lost 13 railway cars during that blaze. In 1920, a CG&W trolley traveling from Pen Mar crashed, killing a company engineer. Then, the personal freedom cars allowed was a final blow. By 1932, local trolley service was gone forever. But Cold Spring Park was a cherished venue, and people still visited in large numbers whether they walked, took a bus, or drove their cars.

A few years earlier, a special man bought Cold Spring Park in 1926. During the next six decades, Robert “Barney” Barnhart devoted his unique energies and showmanship into developing the park, creating new traditions that enchanted visitors. He was a skilled craftsman who built a miniature train in 1944, loved by children and adults alike. Barnhart constructed onsite bridges and a log home for his family. A swimming pool was installed in 1951. That pool was fed by the spring and remained cold even during summer months.

“He was a kind, benevolent man,” Cindy Knauer said about Barnhart, her grandfather. “He didn’t seek riches, but loved life and wanted to entertain people. His wonderful sense of humor was evident in all the fun events at the park.” For most of its tenure, Cold Spring Park didn’t charge any fee for picnics and family events.

Guests at the Historical Society event remembered many activities at the park: chasing greased pigs, feeding goldfish, eating Stover’s ice cream, women in bonnets playing croquet, being chased by a pair of geese named Pete and Tilley, plus many dances, concerts, and picnics. One woman in her 80’s said: “Cold Spring Park was the place to be seen on summer weekends.” Another man recalled: “You were treated like family when you went there.”

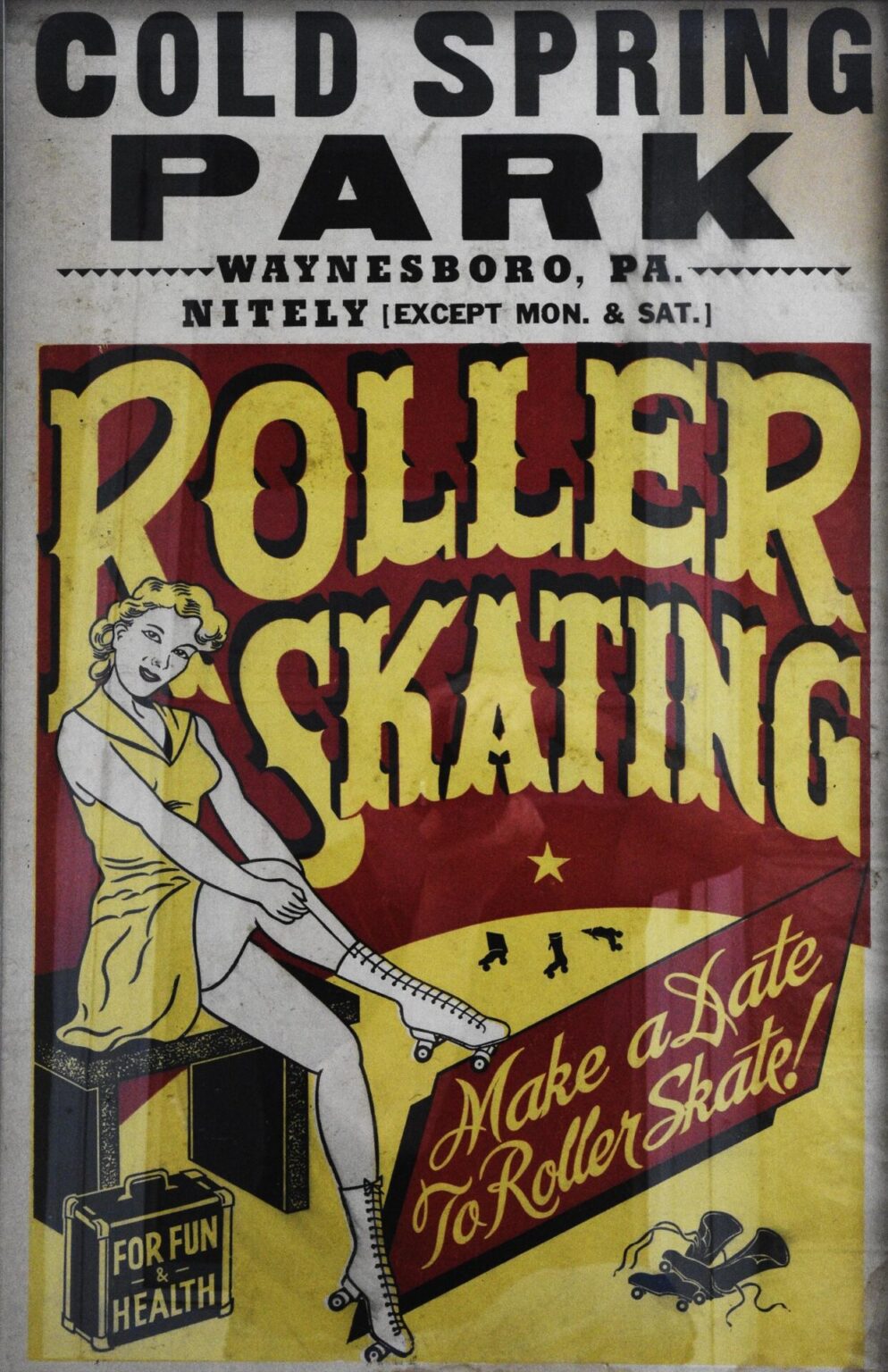

But one Cold Spring Park attraction was recalled most by all: the skating rink. On summer weekends, this building was the center of park society. One visitor recalled how she saved her childhood babysitting money to create her own costume and pay for skating time. The cost to rent skates and use the rink back then: 35 cents. Another woman remembered a park employee named Billy, a handsome skater. Young women would intentionally fall off their skates near him, hoping he’d help them to their feet.

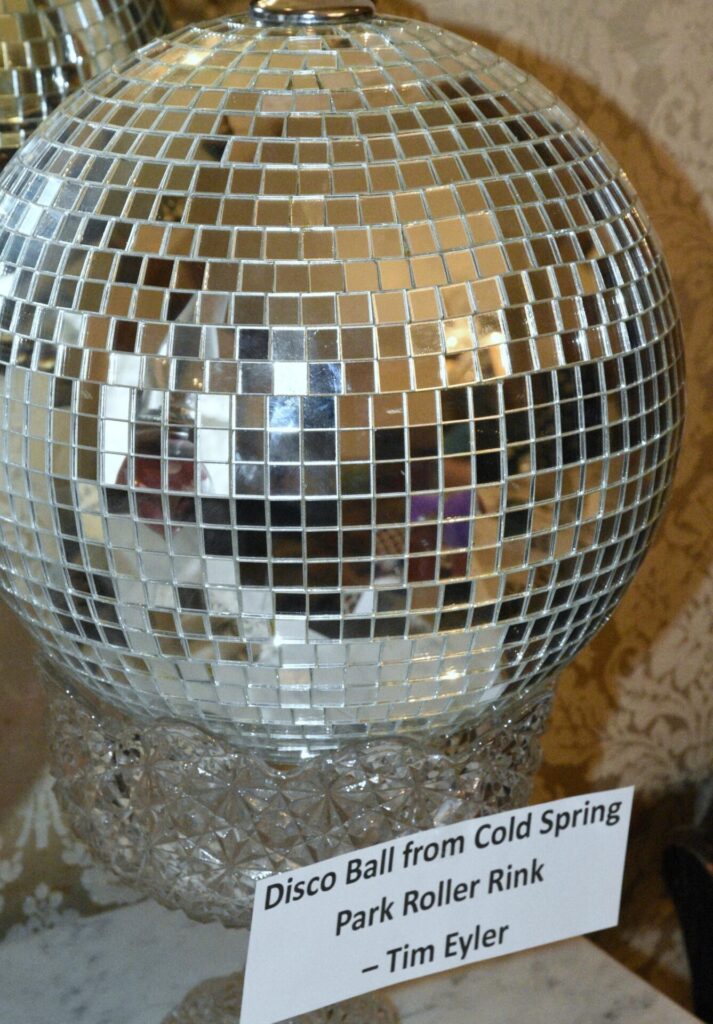

The park sponsored Speed Skaters, Waltzing Skates for couples and Moonlight Skates at midnight. Doubtless romantic introductions followed. When a heavy rain occurred, the rink’s roof was a notorious leaker, causing the floor to buckle and hump in places. Open windows sometimes invited flying bats inside. But nothing dampened skaters’ enthusiasm; they happily dealt with the rink’s quirky idiosyncrasies. Before the 70’s dance craze, a Disco Ball hung from the ceiling and it was displayed at the WHS event.

The rink survived two years past the park’s closing, and was supposedly the longest continuously operating skating venue in the country during its era.

Robert Barnhart sold the park to his son Merle in 1973. Merle ran the park until its closing in 1984. Since then, the property has been owned by several church groups and closed to the public.

The swimming pool was filled in, the miniature train moved to Red Run Park, and many of Cold Spring’s artifacts were sold at auction. But the creek still flows and warmhearted memories remain.

That fondness was clearly evident at WHS’s event as people laughed, cheered, and celebrated Cold Spring Park’s history. They leafed through picture albums, marveled at old skates, and inspected vintage postcards. As stories were swapped, they recalled how the park’s beautiful natural setting, along with its whimsical man-made attractions, served as a treasure chest of memories.

Most in attendance agreed; life’s exceptional places are often appreciated more after they’re gone. Afterward, indelibly imprinted memories are best shared with others who experienced those same bygone venues that brimmed with happiness and pleasure.