During America’s Civil War, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman uttered a famous quote: “War is hell”. Sherman’s scorched-earth campaigns never touched the Cumberland Valley, but his observation about warfare’s cruelty certainly proved true for several local towns. They faced a harsh choice during the Civil War: pay a Confederate ransom, or their town would burn. Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and Frederick, Maryland managed those rebel extortion demands differently, and faced their consequences for decades afterward.

During the Civil War’s first chapters, battles were fought in Confederate territory, sparing Union citizens from war’s savagery being acted out on their streets. Then, Robert E. Lee’s forces marched north into Pennsylvania during 1863 and the result was a horrific battle at Gettysburg. Thousands of soldiers died. Civilians were killed in the crossfire. While the southern rebels were defeated, the Mason-Dixon Line had finally been crossed. Going forward, northern citizens held their collective breath.

A year later, Lee and Union commander Ulysses S. Grant were locked in a stalemate at Petersburg, Virginia, near the Confederate capital. Lee needed to clear Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley of an increasing Union menace and also pondered his own aggressive move- an attack on the U.S. capital city at Washington. Lee picked a General for this dual mission. His name: Jubal Early.

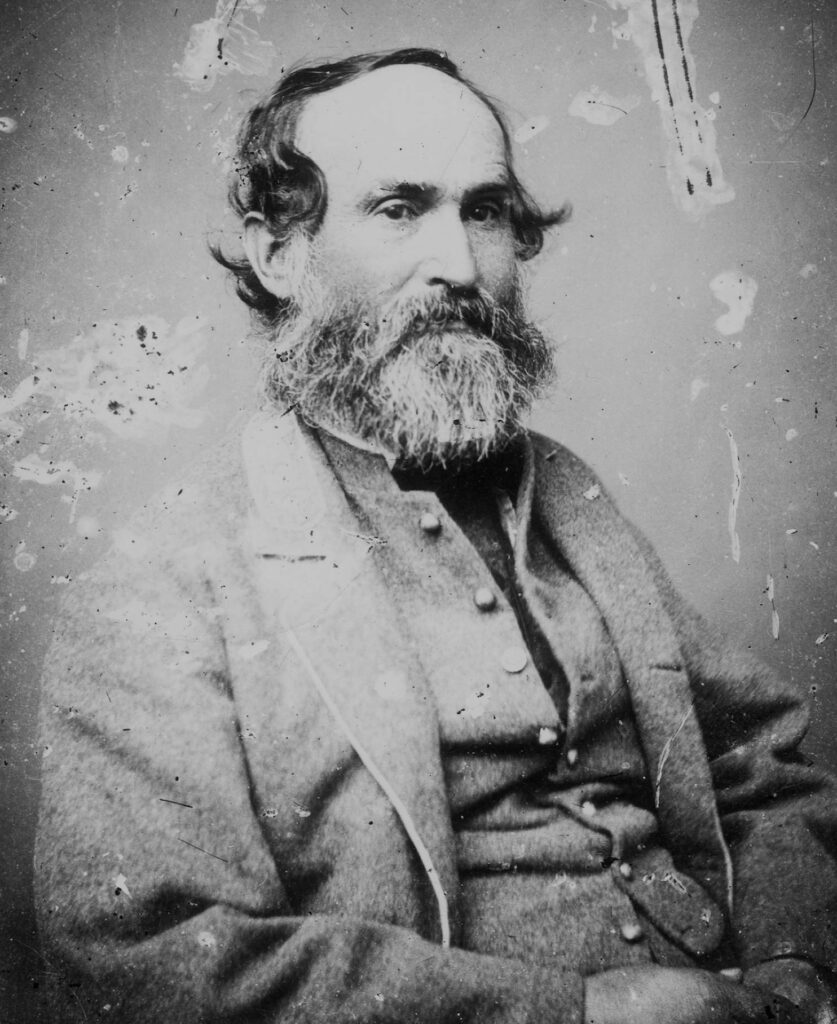

Jubal Early was a classically trained soldier. Virginia born in 1816, he graduated from West Point and served during the Second Seminole and Mexican-American Wars. Early would resign his military commission after each conflict to pursue his other passions: law and politics. He was elected to Virginia’s House of Delegates and later as a County Prosecuting Attorney.

Early’s political career was unremarkable, but he was selected as a delegate to Virginia’s 1861 secession convention. He was a staunch unionist and voted against separation. However, when his state seceded from the Union, Early’s loyalties led him to accept a Confederate Army commission.

After commanding divisions at major battles of Fredericksburg, Antietam, and Gettysburg, Early attained rank of Lieutenant General. Robert E. Lee called Early his “Bad Old Man” due to his propensity to curse, anger quickly, and act insubordinate. But Early’s men loved their commander and fought hard under him. With Lee’s confidence, Early commanded the Valley Campaign in 1864.

One Shenandoah Valley incident that spring infuriated Early and influenced future actions. Union General David Hunter raided the valley and burned Virginia Military Institute on June 11th. Hunter also torched several homes of prominent Virginians, including a former Governor. Shortly afterward, Early moved his forces north with eyes on Washington, DC, but his vengeful heart was still in Virginia.

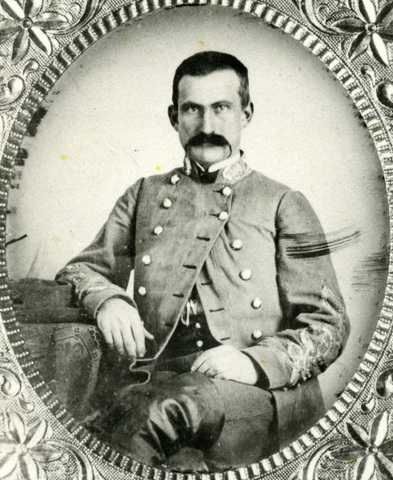

In late July, Early ordered his cavalry commander, Brigadier General John “Tiger” McCausland, to ride toward Chambersburg. Nearly 3,000 horsemen answered to McCausland. On July 29, they encamped outside of town. The closest Union soldiers were stationed at Greencastle and thought McCausland’s men were a greater threat to Baltimore. With that mistake in judgment, Chambersburg was left defenseless.

McCausland held specific instructions from General Early: ransom Chambersburg for $100,000 in gold, or $500,000 in cash. If the town failed to comply, McCausland had blunt orders: “burn the entire town.” He rode into Chambersburg and calmly explained the Confederate extortion demand. Chambersburg had six hours to produce the entire ransom.

Early and his subordinates had the confidence to make this audacious demand in Chambersburg because they’d practiced it several weeks before. When Early arrived in Maryland, he was planning an attack on Washington, but delayed his march to conduct local schemes.

Still angry at Hunter’s fiery destruction in his home state, Early wanted Marylanders to pay. The Old-Line State had not taken his side either; it never joined the Confederacy. When Early occupied Middletown, he proposed a $5,000 ransom. The town produced only a third of that amount, but Early didn’t burn their village. In Hagerstown, his demand increased to $20,000, and the city paid. By the time Early arrived in Frederick, he envisioned a much larger payday.

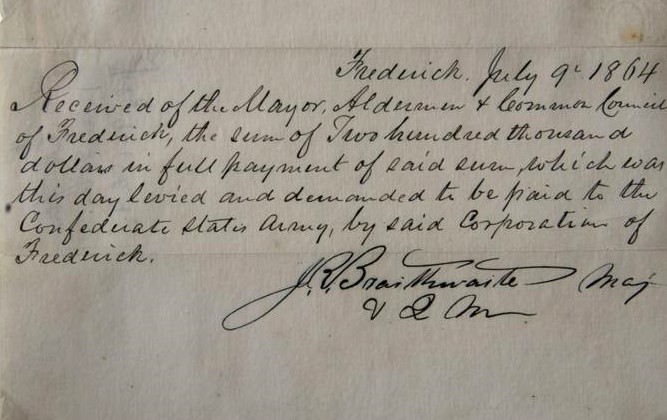

On July 9, 1864, Early sent Frederick Mayor William Cole a written ransom demand. The city must pay $200,000 (nearly 4 million in today’s currency) and also give up thousands of pounds of food supplies. Cole stalled and argued other local towns paid much less.

But Early didn’t back down and Cole was forced into action. The Mayor convinced the City Council to authorize forcing five local banks to hand over a percentage of their capital. The city promised to repay the desperate loan. Local officials delivered the acquired ransom in wicker baskets. The Confederates grabbed the money, and then generously returned those baskets.

With a rapid civic response, Frederick was saved. Later, some asserted Frederick’s ransom negotiation and eventual compliance delayed Early long enough to save Washington too. When Early’s tardy Confederate forces finally reached the capital city, it had been reinforced and remained under Union control.

Three weeks after Frederick’s ransom payment, Chambersburg stood in Early’s crosshairs. But local resources were depleted. Chambersburg bankers, aware of Frederick’s recent extortion, left town with their institution’s money. Since Maryland towns had escaped Early’s promised wrath- one by paying a fraction of the ransom, Chambersburg might have miscalculated their imminent danger. Only a year prior, General Robert E. Lee had urged civility toward Chambersburg’s civilians on his march toward Gettysburg.

But at 3 AM on July 30, McCausland launched several shells into Chambersburg’s downtown. After several hours passed with no reply from local citizens, McCausland and 500 of his cavalrymen rode into town. Unfortunately for Chambersburg, the Confederate commander quickly lost control of these troops. Chaos ensued.

Rebel soldiers roamed Chambersburg streets in early morning hours, breaking into homes and demanding whiskey and money. They looted personal belongings and terrorized citizens. Confederate General Bradley Johnson later stated “drunken soldiers paraded the streets, pillaging, plundering, and drunk.” One rebel soldier was cornered in a basement and killed by furious townsfolk.

With the town out of control, no ransom money obtained, and Union forces finally closing in, McCausland followed Early’s edict and ordered the town burned. While most followed this evil decree, some Confederates officers refused to obey. One Colonel took his men and left town.

Quickly and methodically, other Confederates went house to house and set them ablaze. For extra drama, they used explosives to blow up the Franklin County Courthouse. One witness said: “tall, black columns of smoke rose up to the very skies…gigantic whirlwinds lifted burning articles into the air, intermingled with shrieks of women and children”. 2000 panic-stricken citizens lost their homes as over 500 buildings were completely destroyed. Damage was estimated to be $1.6 million dollars. In a few short hours, Chambersburg lay in ruins.

Jubal Early later stated Chambersburg was picked solely because it was the largest northern city accessible to his troops. He admitted he ordered the town’s burning without authorization from superiors. “For this act, I alone am responsible.” After the war, Early fled to Mexico, then Cuba, and eventually settled in Toronto, Canada. After a pardon by the U.S. Government in 1869, Early returned to Virginia, but remained an unreconstructed rebel until his death.

Confederate General McCausland, who supervised Chambersburg’s destruction, escaped after the raid, but his forces were hunted down and defeated. He survived the war, and spent time hiding in Mexico and Europe afterward before being pardoned for Chambersburg’s arson. McCausland died on his West Virginia farm in 1927, the last surviving Confederate Civil War general.

While Frederick suffered no catastrophic damage from Jubal Early’s vindictive extortion, they still had a loan to repay. 87 years later, on September 29, 1951, that repayment finally concluded, and with interest that amount accrued to over $600,000. Proposed legislation was debated many times in the U.S. Congress (the first bill in 1889) to compensate Frederick for its wartime ransom payment. To this day, the federal government has paid not a single cent.

Chambersburg experienced a much more difficult road to recovery, but handled their trial with courage and determination. By 1900, the town was completely rebuilt and its citizenry had doubled from its Civil War population. Rather than forget the awful events of July 30, 1864, Chambersburg commemorates the burning in an annual event, to attest how their city was reborn from the ashes of war. Re-enactors and smoke machines recreate that fateful day, when a ransom threat was tragically enforced, and hell was unleashed on a defenseless town.