When the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal’s first-phase eastern section was completed in 1850, the ambitious transportation project was already obsolete. The 184.5 mile-long waterway, engineered and constructed along the Potomac River’s northern shore from Washington, DC, to Cumberland, Maryland, was partially inspired by an early canal advocate: George Washington.

Washington’s “Potowmack Company” formed in 1785 to improve navigation on the river, and it built minor skirting canals around five different Potomac fall areas. At Great Falls, transportation upriver was virtually impossible due to rugged and rocky terrain. Reliable water flow on this river was also inconsistent. But a grand canal design, connecting the Chesapeake Bay with the Ohio River at Pittsburgh, wasn’t signed into law until 1825.

This first major section, linking Washington to Cumberland, began construction in 1828. During a 22-year project, this privately funded undertaking would require 74 locks (to raise the canal over 600 feet in elevation), 11 aqueducts, 240 culverts, and one gigantic tunnel, to bring the canal into existence. The first small section opened in 1831, and completion to Cumberland was achieved nineteen years later.

During almost a century of use, the C&O Canal developed a unique culture of commerce that created a lasting legacy of river communities and spurred the nomadic people who worked the canal. But after its use declined and later evaporated, the C&O would re-invent itself with a healthy variety of new recreation and history opportunities.

When the canal finished its eastern phase to Cumberland, the seasonal labor of boatman, lockkeepers, and mules began. A trip along the entire watercourse normally took seven days, about 26 miles daily. Captains were paid approximately $75 per trip, deckhands about $12. Laborers were promised three meats a day- and a generous supply of whiskey. German and Irish workmen often turned violent over trivial issues and had to be segregated. For a time, whiskey rations were withdrawn, but later those adults spirits flowed again. One year, a cholera epidemic stole unlucky workers’ lives.

Boatmen were a unique breed. These hard-working men, women, and children worked 15-hour days, lived and toiled on cramped cargo boats, and weathered extreme conditions. One boatman described their work ethic: “It never rains, snows, or blows too hard for a boatman.” They fought with lockkeepers and canal authorities. In the off-season, these workers secluded themselves. One tough canal woman gave birth to 14 children, all while living on a boat.

Kids drove mule teams along the towpath- the horsepower for forward movement of cargo-laden canal boats- which carried up to 130 tons. The boatmen often performed their duties recklessly, running at excessive speeds and damaging locks- which raised or lowered boats headed either east or west. Working season typically ran from March to December.

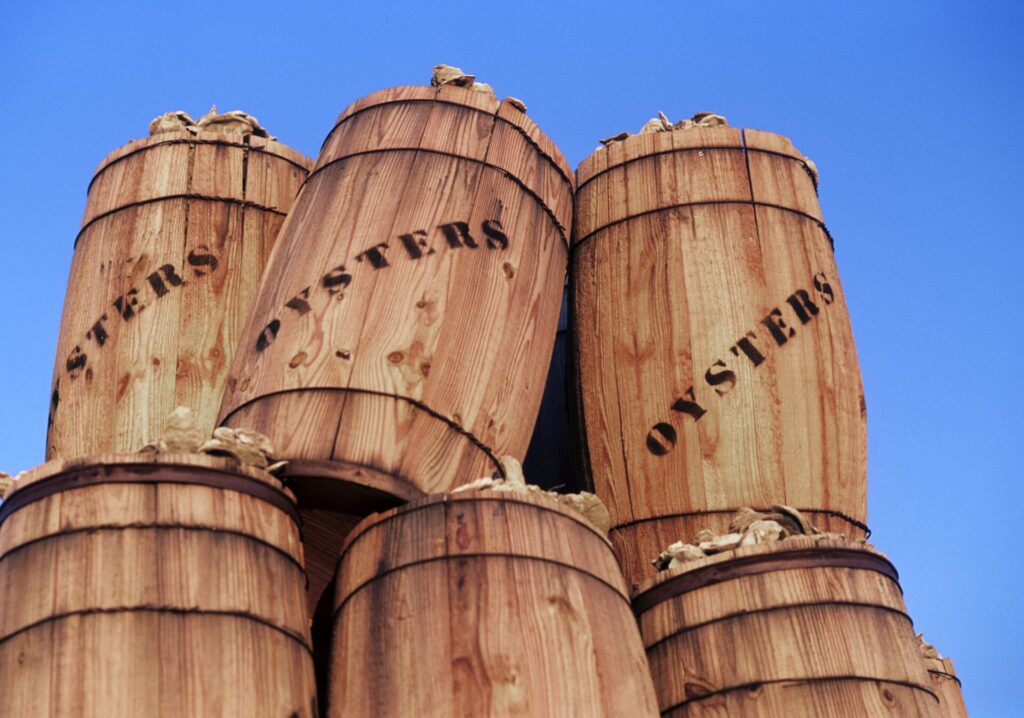

Coal was the major cargo floated down the canal, originating in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains. Lumber and agricultural products were also common. But no freight was off-limits, including pianos, watermelons, and Chesapeake Bay oysters. One story recalls an entire circus transported on the C&O, which included a live black bear. Fees for coal transport were ¼ cent per ton per mile. Whiskey required a 2 cent toll, while bricks or salt were charged a 1 cent fee. The canal was six-feet deep, and ranged from 50 to 80 feet wide.

A variety of boats were utilized on the canal, the majority designed for optimum cargo with minimal drafts. Gondolas, sharpers (flat-bottomed boats) and rafts were used. The latter vessels were often rickety and dangerously overloaded, and then discarded at journey’s end.

Early in the canal company’s working era, a legal fight erupted with its primary competitor, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. They fought over a narrow strip of land near Harpers Ferry- both needed that property’s control to continue smooth operations. Eventually, the two shared that right-of-way, but battle lines were drawn. The B&O beat the C&O Canal Company to Cumberland by eight years, and from the start B&O held major advantages over their competitor.

By the 1870’s, the railroad industry had faster locomotives and could move cargo quicker and cheaper than any canal boat. From its inception, the C&O Canal fought against the current. But during a short 1870’s window, the canal showed a healthy profit. Unfortunately, a natural foe constantly taunted the canal: flooding.

Natural disasters caused massive damage to the C&O canal on several occasions. Like any river, the Potomac was prone to unpredictable flooding, and the canal’s close proximity was a continuing curse. After one flood in 1889, the canal company went into receivership. Eventually, the B&O Railroad acquired a large block of the canal’s bonds and would later attempt (without success) to sell off part of their foe’s property. The C&O Canal’s keepers also fought limestone sinkholes and leak-causing muskrats.

Toward the end of the eastern section’s earlier construction, a massive tunnel was required to finish the route. The Paw Paw Tunnel was an engineering marvel, drilled 3118 feet through a rocky mountain, composed of over 6 million bricks. The projects original budget: $33,000. The final tally was over $600,000 (ten years past scheduled completion) and nearly bankrupted the canal company. With similar rugged terrain between Cumberland and final destination Pittsburgh, any further plan by the debt-laden company to complete a final C&O western leg was considered foolhardy. The “O” reference in the canal’s name would remain an unfulfilled dream.

Yet another flood in 1924 withdrew the final straw keeping a sinking ship afloat. Soon after, the canal closed permanently. Left abandoned, and after another disastrous flood in 1936, the Federal Government obtained the C&O property two years later, but waited until 1961 to declare it a National Monument. In 1971, it was christened the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historic Park and transformation of the canal’s reputation began.

Thankfully, much of the C&O Canal’s infrastructure was later repaired and properly preserved by the National Park Service. That work reformed the canal from an outdated and neglected “Grand Old Ditch” to a national treasure, a linear park stretching from the nation’s capital to Western Maryland. Today, along this path, six Visitor Centers interpret the canal’s storied past. The closest area V.C. is located at Williamsport, Maryland- a prime example of a river town influenced by the C&O Canal.

Williamsport was founded in 1740, but hit its economic stride during the canal’s boom years. At the town’s Cushwa Basin area, modern-day visitors can sample a broad variety of canal history (at mile marker 99.8) in a short section. An old coal warehouse hosts the Visitor Center, a testament to that cargo’s past importance. This basin was one of the only places big enough for canal boats to turn around. Nearby is a trio of architectural artifacts: the only railroad lift bridge on the C&O, Lock 44, and the Conococheague Aqueduct, a beautifully restored stone bridge. The canal’s towpath runs past all three, a connecting pathway to many adventures along the C&O.

This towpath, once used only by mules, is now a hiker, biker, and walker’s paradise. It reveals remnants from the canal’s heyday: locks, re-watered sections, and old lockkeeper’s homes. Along the scenic Potomac River are many opportunities to spot wildlife and other vestiges of natural history. The towpath is utilized for road races too- half of the famous JFK 50-Miler course is run on this trail. Throughout its former path, the NPS hosts seasonal C&O events. Visitors can also camp at designated areas, visit historic river towns like Harpers Ferry, or rent a rustic lockkeeper’s former home for a unique weekend getaway.

The public has a proven love affair with the C&O; over 4.3 million people visited in 2022, making it one of America’s most popular National Park units. Most canal areas are free to the public. For more information, visit the National Park Service (nps.gov/choh), or the canal’s non-profit agency, the C&O Canal Trust: canaltrust.org (240-202-2625).

Railroads and other modes of modern transportation sealed the C&O Canal’s eventual demise, but the continuing legacy of this linear park is the engineering know-how and can-do spirit of America’s pioneers. Along its 184-mile path are preserved relics of their hard work, optimism, and dedication- when early citizens felt an irresistible urge to pilot their boat west.