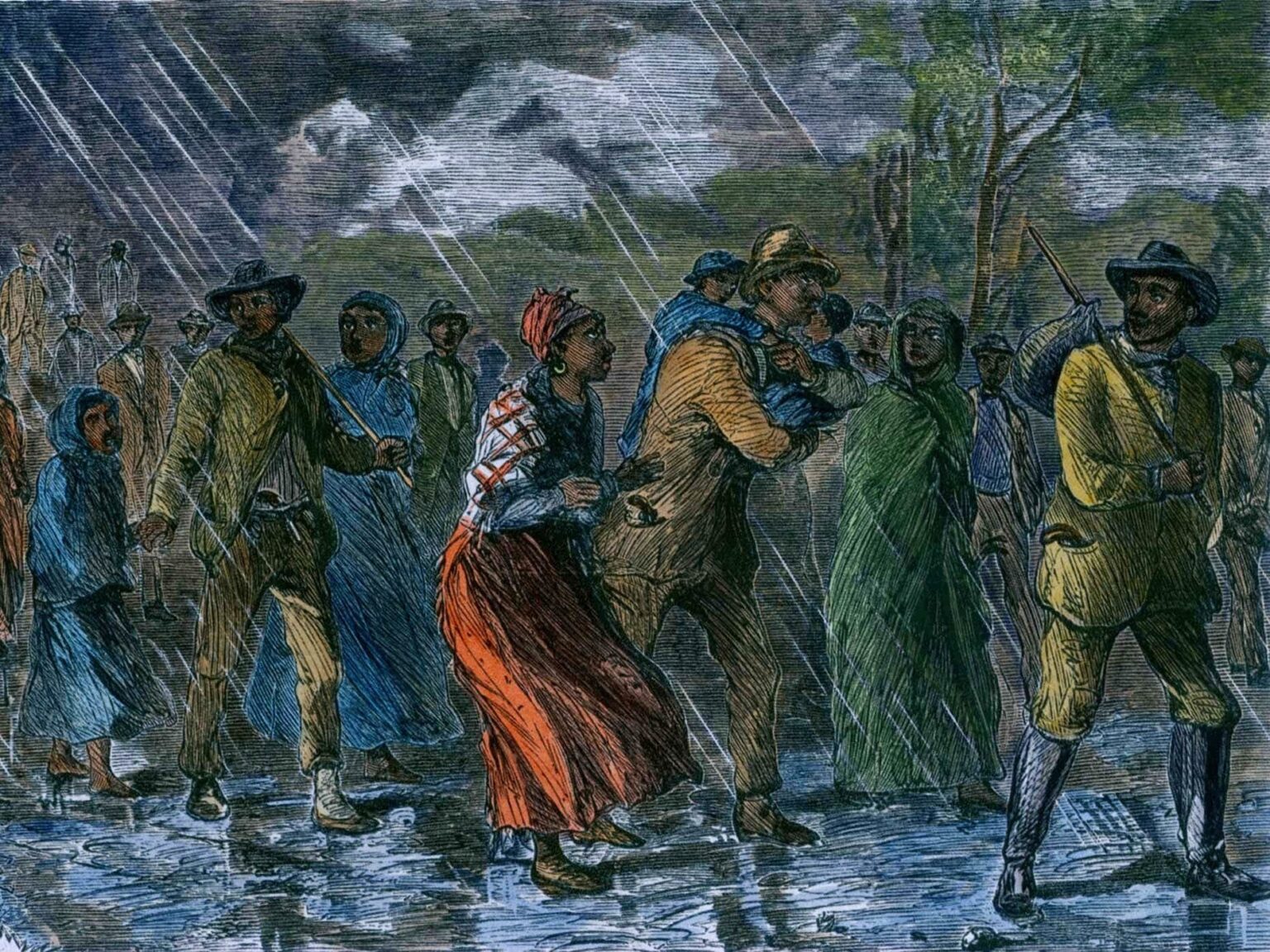

In 1839, a newspaper reported on an escaping slave who hoped to reach freedom on a train to Boston. When that outed “fugitive” vanished from public view, a frustrated slave-catcher reportedly quipped: “There must be an underground railroad somewhere”. That transportation reference was eventually adopted by a historic humanitarian operation. Before slavery was outlawed, up to 100,000 enslaved Americans traveled to freedom on the legendary Underground Railroad- at deadly risk to themselves and the people who helped them.

The movement to free enslaved people utilized railroad terminology to facilitate their missions. Freedom seekers were called passengers and their guides were known as agents or conductors. “Station Masters” hid passengers in their basements, barns, or churches. But the Underground Railroad was generally a loosely organized, word-of-mouth operation. In addition, there was no network of hidden tunnels or secret train tracks leading to safety. The term Underground Railroad was entirely symbolic.

During this dangerous operation, which lasted decades, The Mason-Dixon Line was more than a state boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland. That historic line was the demarcation between enslaved and free. With 200 miles of border between the two states, there were many places to cross over.

The terrain in Maryland’s Washington County offered unique advantages for a planned journey to freedom. The Potomac River was a fluid highway, with a web of wetlands and creeks that aided camouflaged travel.

The nearby Appalachian Mountains were a rugged territory of forests and coves that concealed freedom seekers during daylight hours. The challenge was finding agents familiar with those secluded highlands who would lead enslaved people north to safety during the dark of night.

As the largest Maryland community with close proximity to the Pennsylvania border, Hagerstown was a logical staging area for a covert trip north. In 1820, 14% of Washington County’s population was enslaved. When the Civil War began, 1500 locals were still held in slavery. While it’s impossible to know everyone who helped in Maryland’s secret network, a few Washington County citizens are notable.

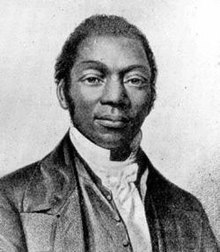

James W.C. Pennington (born James Pembroke) was born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and then brought to Washington County at age four. The Rockland Plantation, located south of Hagerstown, enslaved him. In 1827, aged 19, James escaped into Pennsylvania. He changed his name, went to Yale University, and later became a Presbyterian Minister. James also helped several family members escape Maryland into freedom. In 1849, Pennington authored the “Fugitive Blacksmith”, a compelling memoir detailing his experiences on the Underground Railroad.

Henry O. Wagoner was another prominent Washington County resident, born a free black in 1816. After coming under suspicion as a local Underground Railroad conductor, he moved to Chicago where he befriended Frederick Douglass and worked openly for abolition. Wagoner later settled in Colorado and became a sheriff.

For most people seeking escape from slavery, Maryland offered limited resources. The state’s western sections had scattered pro-Union loyalty prior to the Civil War- and Maryland never joined the Confederacy- but the fact was that slavery was still legal in the Old Line State. The horizon looked brighter once freedom seekers crossed the Mason-Dixon Line.

But entry into Pennsylvania didn’t guarantee immediate freedom. For most, entering Franklin County or other Commonwealth counties offered a temporary moment of relief. A large number of free African Americans lived in Franklin County in the mid-1800s. After an enslaved arrival, local black citizens schooled their brethren on tactics to assimilate them and then move onward. Mercersburg had a thriving population of freedmen, and they showed escaping slaves old Indian trails that led north.

Unfortunately, after the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850, bounty hunters and slave-catchers held unfair advantages when chasing human property. This law deprived African Americans their right to defend themselves in court- making it impossible for even free men to prove their status. Slave-catchers knew escape routes and offered rewards, enticing locals to turn in so-called runaways. State lines did not deter their efforts. As a result, some free blacks (including children) were sent further south into slavery along with re-captured slaves.

With the stakes high, and the deck stacked against their side, Underground Railroad organizers constantly improvised. A network of safe houses was established, many run by religious sects such as Quakers, the Wesleyan Church, or the Reformed Presbyterian Church. For further safety, most conductors only knew short sections of the escape route, and then passed travelers on to the next agent in the chain.

One participant remembered Franklin County as “a hazardous area which contained the most secretive, tangled lines of the Underground Railroad.”

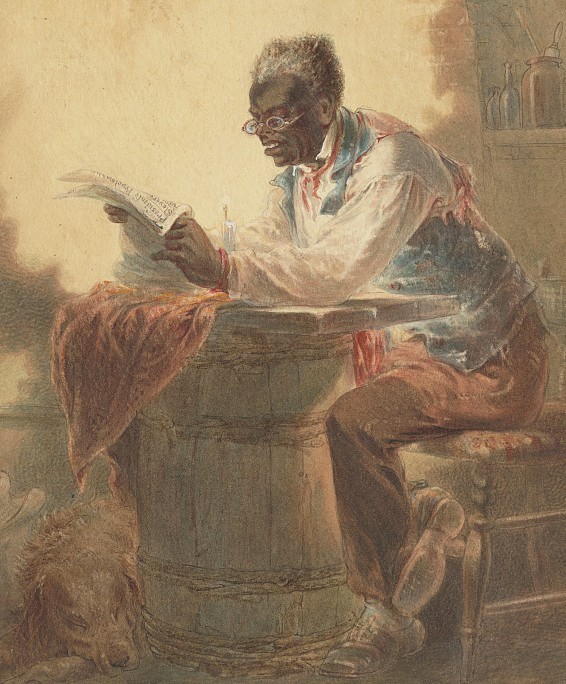

Freedom seekers used disguises and forged documents to increase their chances of success. They normally traveled on foot, or were concealed in wagons inside hidden compartments, or sheltered under produce or hay. A few fortunate travelers found a horse for increased speed, but most escaping slaves had no financial resources.

One escape route entered Franklin County, in the shadow of South Mountain from Smithsburg, via Midvale Road into Rouzerville. There, at the Shockey Farm, a son remembered their secret guests: “they came to my father’s barn, where they generally arrived in early morning. I fed and guarded them during the day.”

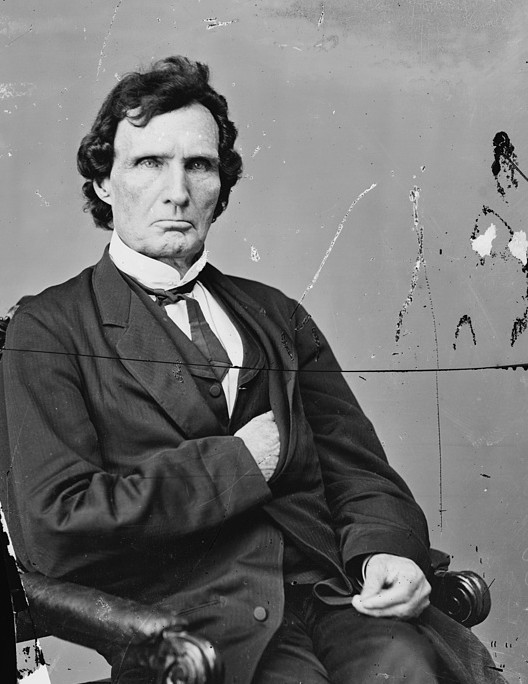

Next, fleeing travelers entered Quincy in darkness, where they were sheltered at the Hiram Wertz Farm. Continuing north to the Caledonia area, freedom seekers passed into the care of Thaddeus Stevens and his iron works comrades. Stevens, also a U.S. House Representative, was one of the region’s largest African American employers and a passionate voice for emancipation in Congress. The helpful free black community close to the iron works was known as “Africa”. From that location, passengers were shuttled north toward Harrisburg and beyond.

In Chambersburg, Mary Ritner hosted a safe house. She was the daughter-in-law of Pennsylvania’s abolitionist Governor Joseph Ritner. Mary’s husband, Abraham Ritner, was a real conductor on the Cumberland Valley Railroad, and freedom seekers frequently traveled on northern public railways during their escape. The Ritners were a valuable asset in Franklin County’s network.

Later in 1859, widowed and living on East King Street, Mary Ritner took in a tenant with an alias, calling himself Isaac Smith. His real name: John Brown. Brown was a militant abolitionist with a price on his head. He’d killed two men in “bloody Kansas” and had arrived in Franklin County (and spent time in Washington County too) to plan a daring raid. While in Chambersburg, Brown was busy gathering munitions and didn’t participate locally in the Underground Railroad.

Two prominent African Americans were important players in Chambersburg’s section of the escape route. In the South Ward, Martin Delany and Joseph Winters were both known agents in the Underground Railroad. Delany eventually became the first African American field officer during the Civil War. Winters was an inventor, poet, and songwriter who supposedly arranged a secret Chambersburg meeting between John Brown and Frederick Douglass.

For many passengers passing through Franklin County, the final destination was Canada, which outlawed slavery in 1833. An estimated 35,000 enslaved Americans built a free life there.

Spurred in part by John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid, the Civil War erupted in 1861. Freed blacks fought for the Union, and after Maryland’s Battle of Antietam, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. But it wasn’t until the war officially ended that the United States passed Constitutional Amendments guaranteeing African American citizenship and ending the horrific institution of slavery. The necessity for an Underground Railroad finally came to an end.

While Washington County was not the original departure point for most Underground Railroad passengers; nor was Franklin County the final destination, crossing the Mason-Dixon Line was an important milestone in a quest for freedom. For many, Maryland was the last footstep taken in bondage, and Pennsylvania the first stride into freedom.

In modern times, the history of the Underground Railroad is interpreted in Hagerstown, Chambersburg, and other local communities. For more information, visit Washington County’s

website: (visithagerstown.com) or Franklin County’s online site: (explorefranklincountypa.com), for driving and walking tours of Underground Railroad sites.

Embark on a captivating journey through time with our weekly Local History column, where we unravel the forgotten tales and enduring legacies that shaped our communities. Join us in preserving the rich heritage of our hometowns by sharing your stories or suggesting topics for exploration. Together, let us illuminate the past and inspire the future. If you would like to contribute to local history or have a topic you would like covered please reach out to our news department. [email protected]