During America’s infancy, war was both an inevitable and too-common occurrence. The Revolutionary War was required to win independence, the War of 1812 fought to remind Britain that the United States remained a sovereign nation. With a clear-cut national enemy, America’s citizens rallied behind the flag and honored the service of its military. Early journalists and artists helped foster that sense of unity and national pride. But media from that era often created visual and written works that sometimes romanticized the causes or downplayed the realities of war.

America’s earliest military leaders benefited from those nationalistic efforts. Courageous George Washington was painted crossing the Delaware River; fiery Andrew Jackson sketched as he battled in New Orleans. Few citizens would ever view an actual human likeness or meet those famous generals, but partially through the artists who illustrated their war exploits, both men would later be voted into the presidency.

Then, a new medium called photography came into existence. Eventually, this visual art form changed America’s perception of war by showing unvarnished truths about its harsh human consequences.

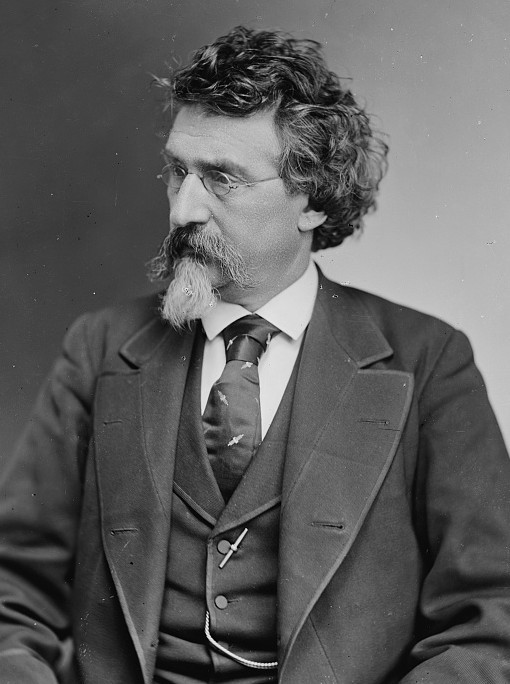

A central figure in photography’s early history was Mathew Brady. For a man later at the forefront of recording 19th century American life, Brady’s birth year remains a mystery. Sometime between 1822 and 1824, Brady was born in rural New York. As a young apprentice, Brady studied under Samuel Morse (inventor of the telegraph) and was taught one of photography’s earliest forms called the daguerreotype.

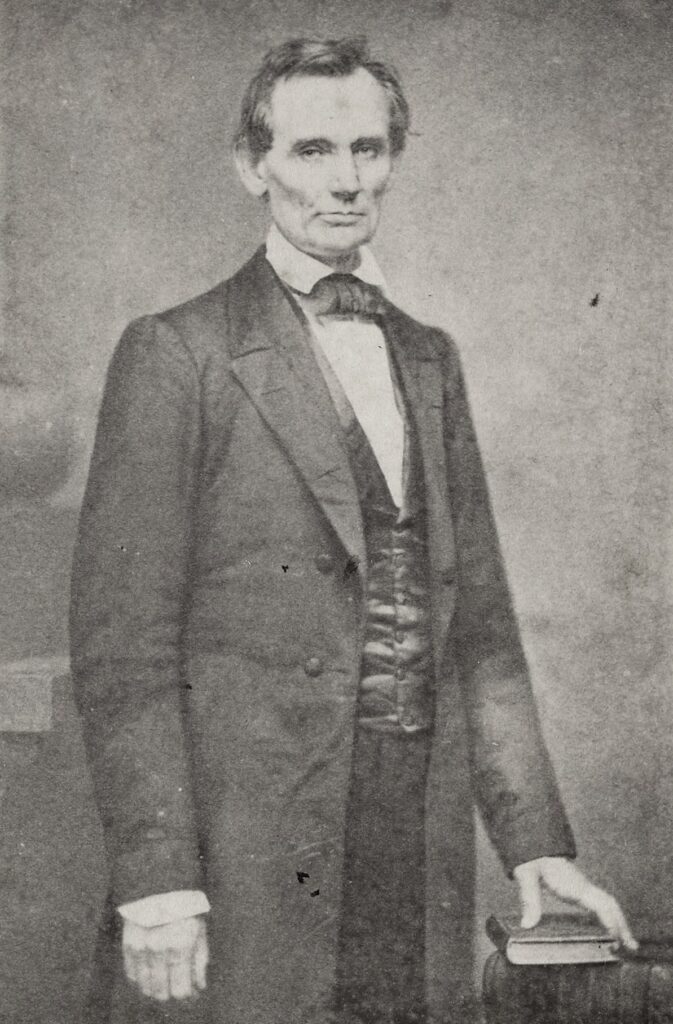

With ambition driving him forward, Brady soon began photographing up-and-coming leaders and prominent citizens. In 1860, he photographed a mostly unknown Illinois politician, known for eloquent speeches. Brady’s portrait of clean-shaven Abraham Lincoln gained national media attention.

Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election and credited Brady’s flattering photograph as a vital campaign tool. Mathew Brady’s later Lincoln portraits were ultimately used as models for the U.S. five-dollar bill and Lincoln penny.

When Lincoln was sworn into office, several southern states had already seceded. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War officially began.

The Civil War catapulted Mathew Brady into national fame. At first, his business plan was providing young soldiers headed to war with pictorial mementos for loved ones back home. A personal photographic portrait was an affordable keepsake. Brady’s art was in high demand.

But Mathew Brady was a visionary and he saw the Civil War’s historic significance. Many citizens assumed the conflict would be a skirmish, over in a few months. Brady thought differently. He decided the epic event needed full documentation. To accomplish this task, Brady not only pioneered new photograph techniques and practices, he became the father of photojournalism.

Photography was a highly specialized skill and cumbersome process in the 1860’s- the medium only a few decades old. Dangerous chemicals used in the development process were an industry hazard. Despite this risk, Brady created a mobile darkroom, delivering his equipment to the battlefield. He gained this special permission directly from President Lincoln.

Long shutter exposures were a necessity during that period, requiring subjects to stay perfectly still for as long as fifteen seconds. Some sitters weren’t patient, and their resulting movement caused the common ghostlike blurred appearance seen in many old photographs. Long exposure times also made photographing battle action nearly impossible. But Mathew Brady realized one photographic subject never moved: dead bodies.

While Mathew Brady’s name is synonymous with Civil War photographs, he couldn’t cover the entire conflict alone. When the war spread to far-ranging states, Brady hired apprentice photographers. But he chose to credit all images with his studio identity, so a “photo by Brady” was often taken by a subordinate photographer. Some of his apprentices later became rivals.

When the Maryland Campaign brought the Civil War near the Mason-Dixon Line, a fortuitous discovery gave the federals an advantage. A copy of General Lee’s battle plans were found wrapped around three cigars. 87,000 troops massed around Sharpsburg in rural Washington County. The battle of Antietam began on September 17, 1862. No one imagined the carnage that followed.

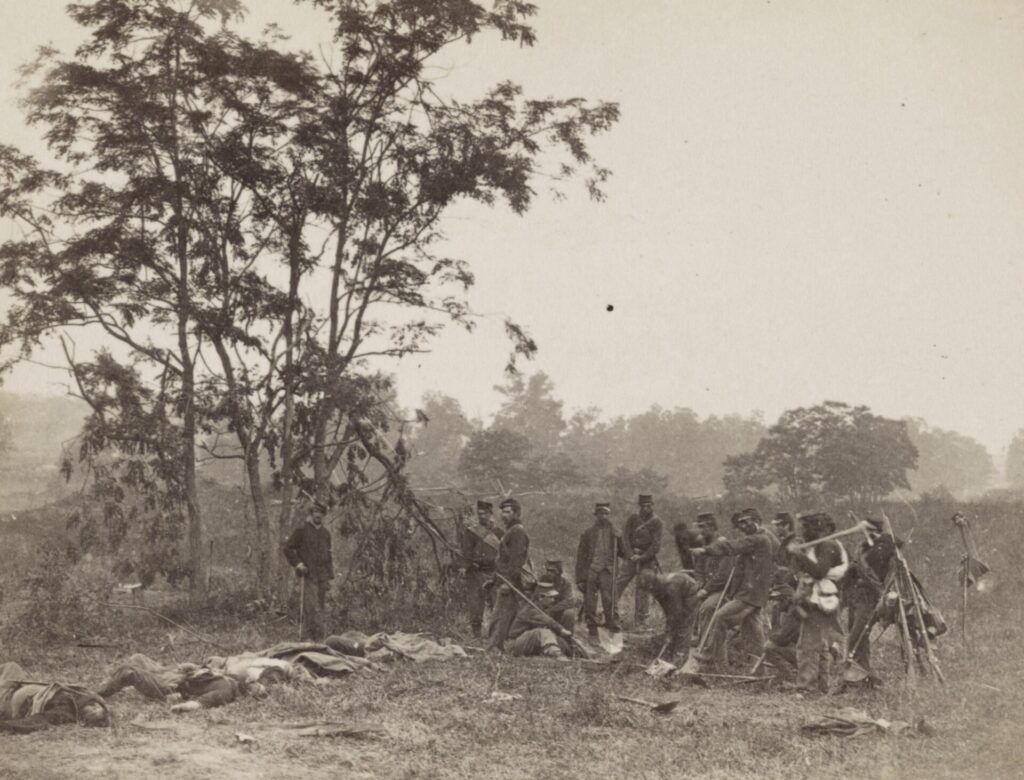

When the battle was over, the Union gained a tactical victory, but almost 23,000 northern and southern men were wounded or killed. It remains the bloodiest day in American history. At one battlefield location, dead men covered the ground, pooled in the depression of a sunken road. That awful site became known as “Bloody Lane”.

Mathew Brady managed his war efforts from studios in Washington DC, and New York City. While he spent little time on battlefields, Brady acted like a film producer, directing his men to capture battle results as realistically as possible. One of his employees, named Alexander Gardner, was a skilled photographer working at Antietam. The Scottish immigrant saw the horrific aftermath, with scores of dead soldiers awaiting burial. Gardner diligently photographed various combat scenes, documenting a grisly human landscape.

Mathew Brady wanted those battlefield images publicized, and one month later he opened an exhibition in New York titled: The Dead of Antietam. A public that was accustomed seeing artificial war illustrations was shocked. One newspaper editorial said: “Brady has laid the Civil War dead at our doorways and in our yards.” The blunt published photographs showed the youthful innocence of killed soldiers, while they suffered the post-battle indignity of lying dead in a field like a wild animal.

An outraged pubic demanded that leaders from both sides find a negotiated truce, but the killing continued. Ten months later, the Civil War came to Gettysburg. The horrific casualty numbers nearly matched Antietam’s. Brady’s photographers arrived in Gettysburg too, capturing on film post-slaughter scenes at places like Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield. America learned why Union General William Tecumseh Sherman said: “War is hell.” Brady and his photographers helped them see that undiluted truth.

When the war finally ended in 1865, Mathew Brady’s continued success seemed guaranteed. He expected the U.S. Government would purchase his immense library of Civil War images. Brady spent over $100,000 of his own money (equivalent to over $1.5 million in today’s currency), creating over 10,000 war scenes.

But post-Civil War America had seen enough, and wanted the conflict’s butchery forgotten. Brady and his men had done their job almost too well, and the government declined his portfolio. Had Abraham Lincoln survived an assassin’s bullet, perhaps that outcome would have been different.

Despite photographing 18 American Presidents and documenting the country’s most epic event, Mathew Brady died a blind and destitute man in 1896. As a final insult to his sad ending, Brady’s modest original gravestone in Washington DC’s Congressional Cemetery incorrectly listed his demise as 1895.

Brady’s immense historic influences were eventually remembered and celebrated. Future photojournalists were inspired by his work. Fifty-eight years after his death, the Library of Congress finally purchased Brady’s war portfolio, securing his legacy. In 2022, Congressional Cemetery dedicated a new Mathew Brady Memorial, which included life-sized bronze statues of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Today, visiting Antietam’s battlefield, it’s hard to imagine how mass killing occurred in such a pastoral and peaceful landscape. Even a contemporary photograph of the infamous sunken road stimulates similar emotions of bygone paintings and drawings- the mown grass and rustic rail fencing soften the now hidden human toll of that brutal battle.

To retain proper historical perspective, the images Brady and his team created over 160 years ago still teach the truest lessons. Those photographs shock modern senses backward in time to awful historical truths told by the ghosts of Antietam.

If you know of local history you would like to share, LocalNews1.org invites you to send your stories to [email protected].