Pottery is of one of humanity’s first inventions, and surviving pieces are evidence of our earliest civilizations. The oldest known samples were found in China, dating back to 18,000 BC. Other key pottery discoveries have turned up in Africa, the Middle East, and South America, ranging from 6000 BC to 14,000 BC time periods. Pottery’s historic story spans the globe. Today, ceramic artifacts give modern archeologists detailed clues how ancient societies were shaped by past social, economic, and industrial influences.

In its infancy, pottery was primarily used as utilitarian vessels for cooking, eating, or other everyday chores. But as more intricate human cultures developed, pottery evolved too, and ultimately it was elevated to an art form with decorative uses.

Pottery is typically divided into three types: stoneware, earthenware, and porcelain. Within this classification, the term Folk Art pottery was coined to categorize hand-crafted works that celebrate important traditions specific to local communities, and to recognize working-class artists.

Another tradition in pottery is that this artistic skill is often passed down in families from generation to generation. During the 1800’s, one local pottery family made a lasting impression, literally carving their moniker hundreds of thousands of times into finished pieces of clay. They were the Bell family. Peter Bell (1775-1847) was the senior potter, and he had three sons, John (born in 1800), Samuel (1811), and Solomon (1817). All would practice ceramic art.

Peter Bell set up his first shop in Hagerstown, and then moved his family to Winchester. Later, Peter’s sons would venture in opposite directions. Solomon and Samuel would settle southward in Strasburg, Virginia. John Bell would eventually prosper up north in Waynesboro after a brief stay in Chambersburg.

Between them, the Bell family produced tens of thousands of pots annually. Since they worked every year during the 19th century, it’s estimated over a million pieces were created. Many local homes utilized Bell pottery for everyday living. Most Bell creations were earthenware, with the remainder being approximately 10% stoneware.

Despite the busy beehive of Bell kin creating pottery in the Cumberland and Shenandoah Valleys, one of the family’s creative efforts would eventually make him more renowned. That potter was John Bell. He had intrinsic qualities that pushed him to excel. One story suggests he first learned pottery from his father at age six.

Some speculate John’s eventual fame was due to a competitive nature, while other scholars mention his innovative glazes and wiliness to copy other artists or experiment. John Bell was the first American to make use of a tin glaze that produced a white surface similar to stoneware.

Samuel and Solomon Bell also produced excellent work in Virginia. Like brother, John, their children followed them into the pottery business. But after the Civil War, the market for local handmade pottery pieces toughened. Mass production made it difficult for individual potters to earn a living.

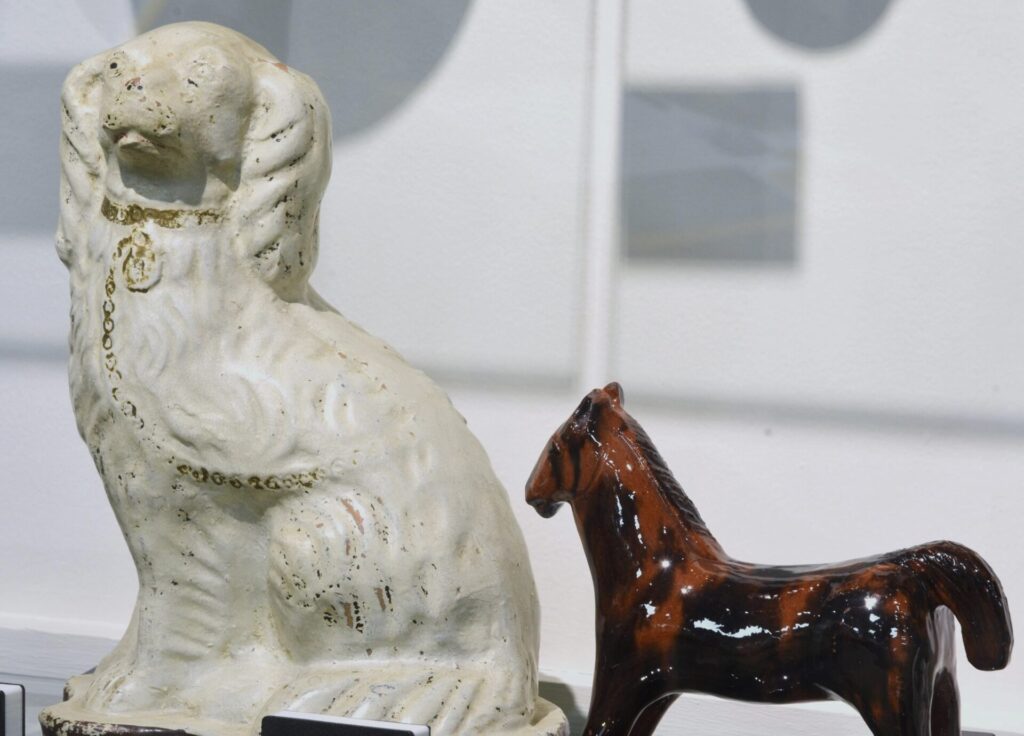

But the Bells adapted, and began producing a larger selection of decorative, one-of-a-kind pieces that were more whimsical and catered to new trends in home decor. They crafted flower pots and animals figurines (dogs, birds, roosters, and goats), among other decorative pottery. By the 1870’s, painted specialty pieces were typical Bell offerings.

John Bell died in 1880 as a well-respected craftsman, but not yet a nationally known artist. One of his sons, John William Bell, took over his father’s business and ran it until his death in 1895. Other Bell children later carried the torch, including daughter Henrietta, but after a Waynesboro fire in 1899, the local business was eventually snuffed out.

The Bell’s Waynesboro pottery shop was located at the southwest corner of Main and Potomac Streets, but their building no longer exists. The Strasburg, Virginia operation lasted a few years longer (several structures would survive for a few decades), but by 1915, the Bell family pottery operation faded into history.

When artists die and creativity ceases, most of their work typically remains unknown, gets discarded, or is sadly forgotten. But the Bell legacy lives on, as many collectors have gained immense appreciation for their skill and artistry, built over a century of work. John Bell’s pieces are highly prized (sometimes fetching five-figure price tags at auction), but John’s brothers, children, and other relatives also became collectable pottery artists too.

One local Bell collector was Emma Geiser Nicodemus. Mrs. Nicodemus and her husband Edgar bought a Waynesboro Federal era farmhouse in 1942. As they renovated the property, their goal was to create a showcase home that celebrated the Early American Period (1790 to 1860).

Emma had a good eye for art and bought pieces that reflected her tastes. She was fond of Bell pottery. A favorite from her collection was an impressive pair of ceramic lions, attributed to Solomon Bell. When widow Emma Nicodemus passed in 1973, she bequeathed her entire 100-acre estate as a perpetual museum. It became known as Renfrew.

Mrs. Nicodemus’s lifelong possessions make up the bulk of Renfrew’s current collection of decorative arts and other artifacts, which consists of over 5000 pieces. The Bell family pottery anthology is beautifully highlighted in an upgraded exhibit space at Renfrew’s Visitor Center. Over 300 pottery pieces are presented, showcasing a diverse range of the Bell’s work.

Viewing the collection, it’s evident how talented and prolific the Bell’s were during their lifetimes. It’s also satisfying seeing their craft preserved for future generations to study and enjoy. Renfrew’s pottery exhibit also provides context to their vast collection. Rather than simply admiring a fascinating multitude of pots, interpretive materials provide visitors with well-researched insight into the Bell’s artistic background. Unique items are also displayed, including plaster molds the Bells utilized to create various forms.

The Renfrew Museum Visitor Center is a free venue, located at 1010 East Main Street in Waynesboro. Renfrew Museum and Park also hosts various events throughout the year that advance their mission to interpret a historic Pennsylvania German farmstead. For more information contact Renfrew at 717-762-4723, or visit their website: renfrewmuseum.org.

Bell pottery is curated in other impressive venues as well. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is one prime example. The continued admiration for the Bell’s creations shows how a local family-run operation can create big ripples in the art world as well as educate many others about early American lives.

For a contemporary look into the art of pottery, Waynesboro’s Nicodemus Center for Ceramic Studies (Named in honor of Renfrew’s Emma Nicodemus) showcases talented modern potters, while also conducting an arts studio program. Their gallery at 13 South Church Street (waynesboroceramics.org, 717-372-7906) is open Friday and Saturdays from 10 am to 2 pm.