Eons before humans explored the Appalachians, powerful geologic forces sculpted that storied mountain chain. Massive collisions between ancient continents caused rocks to be uplifted and folded under tremendous pressure, creating unique mountain features. This remarkable construction process began more than a billion years ago.

During the Cambrian period, most of modern-day Maryland was under water. But in future years, as colossal land masses continuously shifted and oceans diverted elsewhere, the Appalachians began asserting dominance over a drier landscape. Some geologists estimate their peaks were once twice as tall as the Himalayans. Imagine a 50,000-foot-tall mountain in western Maryland.

Despite the uplifting of the Appalachian chain, which eventually stretched from the southeastern U.S. northward into Canada, millions of years of subsequent weathering and erosion lowered the range to the appearance seen today. Now, the highest point in the Appalachians is 6684 feet above sea level, the elevation at North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell.

In what is now Washington County, Maryland, the Weaverton Formation was created around 545 million years ago. The Buzzard Knob landform within this formation is mostly composed of quartzite, which is metamorphosed sandstone. On the western slope of Quirauk Mountain, Washington County’s highest point (2145 feet), an ancient Buzzard Knob rock face was left exposed on a steep slope. It is known today as High Rock.

Standing on its craggy surface, with a constant breeze ruffling leaves of nearby summit hardwoods, a modern visitor is awestruck by the 1835-foot-high panoramic vista High Rock affords of a green valley spread out far below.

Before High Rock achieved its current reputation, the rounded Appalachians were a barrier to human civilization. As America pushed westward, this gigantic north-south land mass was an obstacle to territorial expansion. But as technological advances made trekking easier, the Appalachians were later seen as a tonic for escaping crowded cities in a growing country. Fresh air and scenic vistas awaited intrepid travelers.

One man’s engineering vision, combined with marketing savvy, brought those new-age tourists to Washington County. His name was John Mifflin Hood. A confederate Civil War veteran, Hood later became President of the Western Maryland Railroad. He recognized the region’s natural beauty that straddled the Mason-Dixon Line. Hood also recalled High Rock’s former use as a strategic military lookout.

If Hood could properly promote the company’s newly acquired Maryland mountain property as a tourist destination, scores of people from Baltimore and Washington might visit the area. Western Maryland Railroad trains would deliver them in style and comfort.

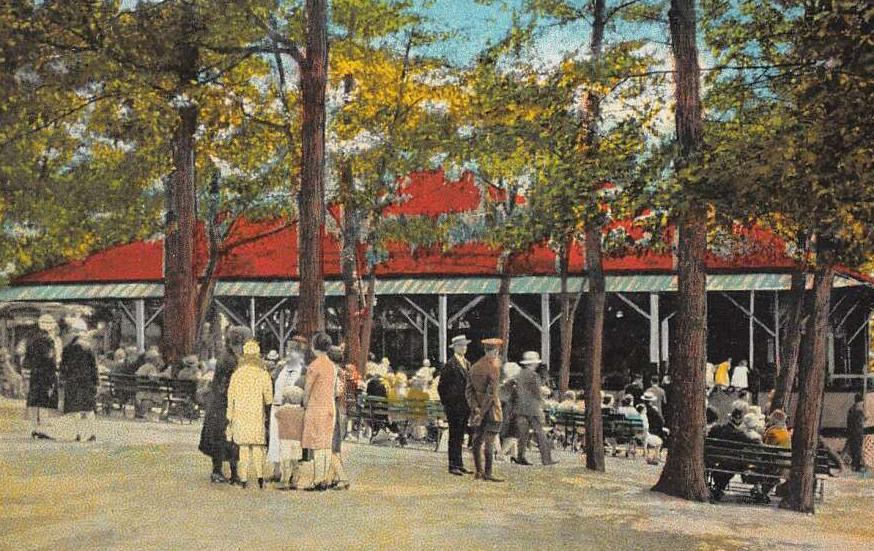

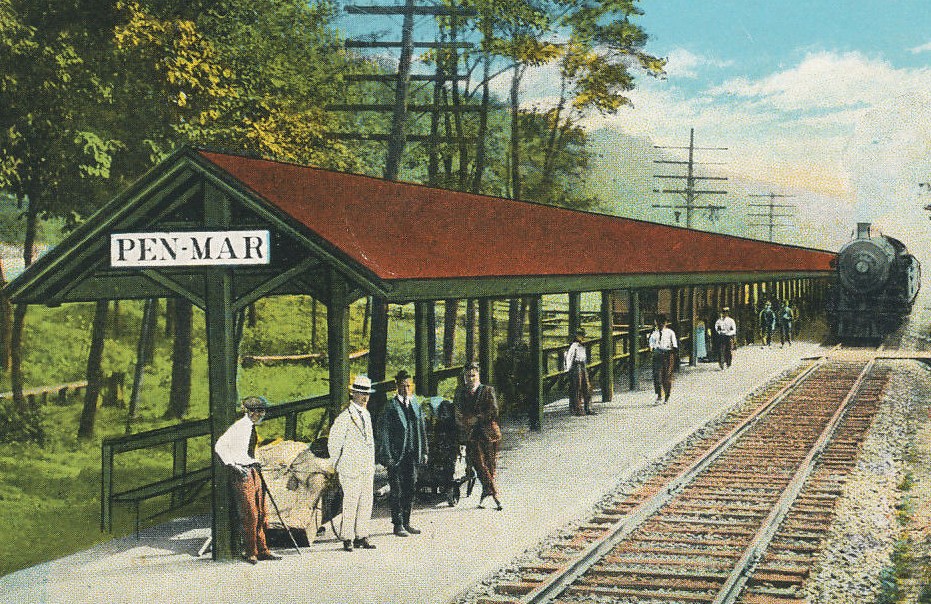

To begin, the Western Maryland Railroad laid track to a handsome new train station. They called their adjoining attraction Pen Mar Park and opened it in 1877. During the next half-century, the park became one of the eastern U.S.’s most popular resort destinations. It boasted a dance pavilion, roller coaster, a 450-person dining hall, photo studio, and a movie theatre. During busy summer months, upwards of 20,000 visitors would pack into the park.

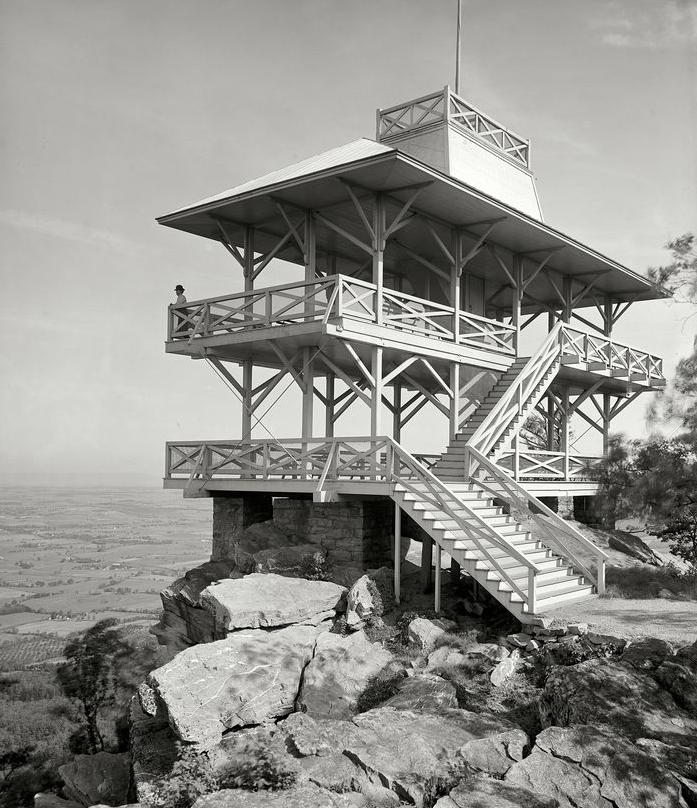

In the bustling community of Pen Mar, enormous hotels and quaint boarding houses sprung up to accommodate those large crowds. A short distance up the mountain, a two-story viewing tower was placed on High Rock, which afforded a better view than Pen Mar’s lower elevation.

The automobile’s introduction in the early 1900’s ultimately brought an end to railroad-brought mass travelers. Pen Mar Park officially closed in 1943 (it would happily reopen as a trimmed down county park in 1977), but High Rock’s popularity continued to grow. However, unlike the slow geologic process that formed the outcrop, changes evolved more quickly by human hands. A paved road to High Rock would eventually bring new types of visitors.

Even as cars increased American’s independent mobility, another man sold his concept for the restorative value of hiking. That visionary was Benton MacKaye. His 1930’s linear creation: the Appalachian Trail. The 2100+ mile footpath would eventually stretch from Georgia to Maine, and wander through Maryland past High Rock overlook.

MacKaye’s grand nature-based experiment was hugely successful, and the High Rock location would serve as an awe-inspiring rest stop near the trail’s center point; approximately 920 miles north of Georgia’s Springer Mountain terminus, and 1080 miles south of Maine’s final mile at Mount Katahdin.

Traveling north into Pennsylvania, a new generation of hikers would cherish scenic overlooks along the A.T, but also curse the stony geologic shards jutting upward through the famous trail’s dirt pathway. After their tortured feet were bruised and blistered, they nicknamed this section of the A.T. “Rocksylvania.”

In the early 1970s, a daring new recreation craze launched in western Maryland. A man named Jerry Lanham performed a daredevil act no one attempted before at High Rock- he leapt off the precipice with a hang glider on his back. As he discovered, the rock outcrop offered perfect conditions for his sport- a large natural launching platform (the viewing tower now gone), a prevailing westerly wind to give his glider lift, and unrivaled views once aloft. Other hang gliders would follow Lanham’s brave example. Before long, High Rock was known as the preeminent launching spot in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Hang gliding’s popularity was tempered by its infrequent tragedies. There was an inherent risk to engine-less flight, one that could potentially end in death. But the sport was relatively safe when pilots were properly trained, supported by fellow gliders, and utilized quality equipment. Despite that others also perished in outdoor activities such as scuba-diving, skiing, surfing, and even cycling, fatal hang glider crashes at High Rock made for bigger headlines.

After the September 11th attacks, there was also concern about a hang glider’s ability to sail over nearby sensitive areas like Camp David or the mountaintop communication towers used by the Department of Defense. Local officials eventually instituted stricter guidelines for High Rock launches. Like Pen Mar Park, High Rock is now administered by the Washington County Parks Department.

In recent times, High Rock suffered a transforming episode- a branding that normally affected mostly urban or deserted objects. Multi-colored graffiti was spray-painted unto High Rock’s natural gray-blue surface. While some contend graffiti is an art and a form of free expression, others argue it is defacement of public property.

Seeing the chaotic and random nature of the current High Rock site, which is akin to having thousands carve their initials into every tree trunk in a pockmarked forest, it appears this altered landscape has suffered a man-made attack of pure vandalism.

Several attempts have been made to remove High Rock’s graffiti. These pressure-washing efforts are time-consuming and expensive. Unfortunately, unknown vandals reappeared after each cleansing and repainted the rock.

Despite the graffiti, the vista from High Rock is forever unspoiled. On a clear day, distant mountains are visible across the valley, the foreground dotted with miniature farms and rolling hills. Emerson once said that “the health of the eye seems to demand a horizon. We are never tired, so long as we can see far enough.”

At High Rock, that horizon awaits, offering a geologic vision of Maryland and Pennsylvania that constantly evolves at a much grander scale than any civilization or person could ever diminish.