Gettysburg is a time capsule of American history contained within a lovely small town. The epic Civil War battle that took place there in July, 1863, is still analyzed today. The Union won that confrontation but the Confederates later escaped across the Potomac River, back into southern territory. The Civil War would rage onward for almost two more years.

Each year, more than a million visitors arrive in Gettysburg to experience the charming community and its preserved battlefield. When touring the area, they can interpret over 1300 monuments spread across the countryside. Some memorials honor past leaders, soldiers, or combat units, while others compliment the physical landscape they rest on. A few monuments evoke artistic or architectural inspiration, while one particular memorial challenges humanity to coexist in a world without war.

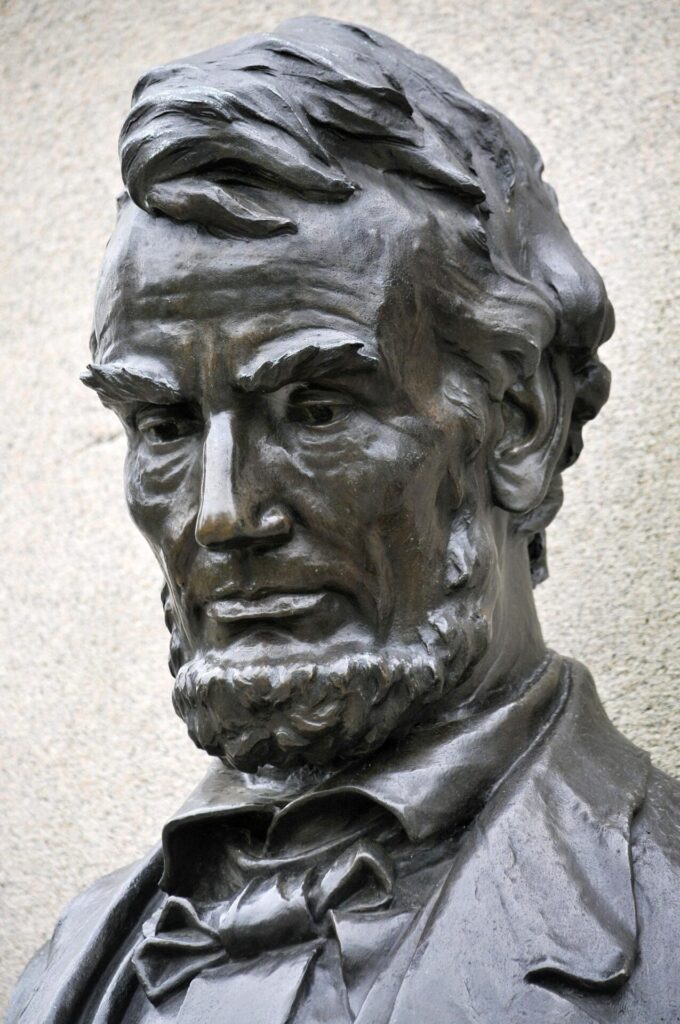

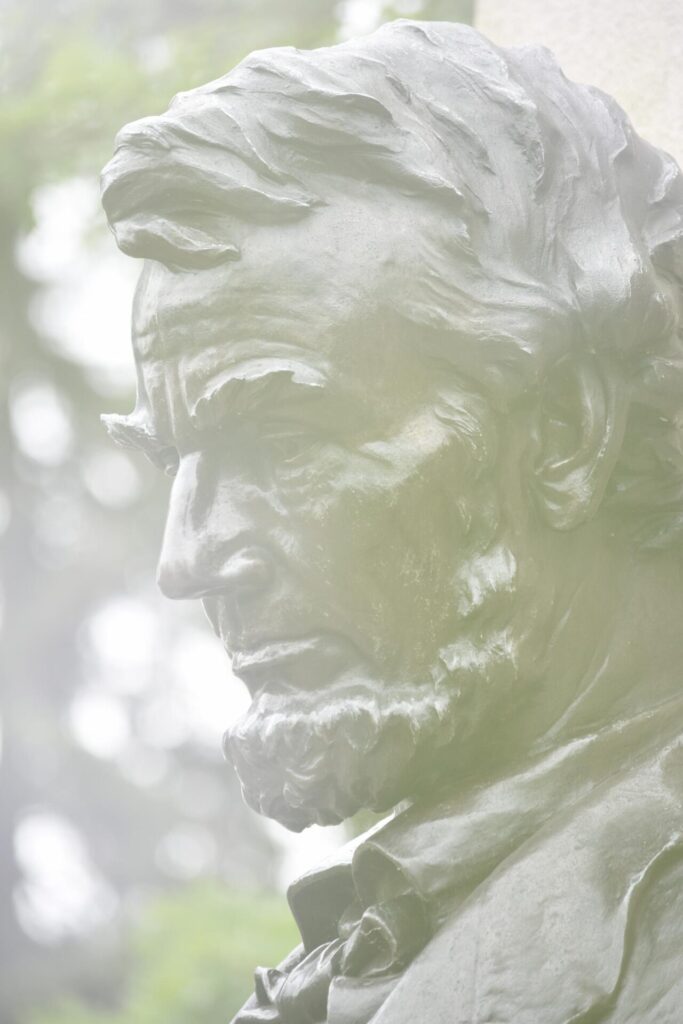

The Civil War was a catalyst for American monument building. After the conflict ended, bronze and marble figures sprung up in courthouse squares, parks, and former battlegrounds throughout the country. Gettysburg’s post-war remembrance began on November 19, 1863. On that autumn day, America’s leader journeyed to Gettysburg to give a speech. The somber occasion was the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, adjacent to the battlefield.

With carefully chosen words, he began his eulogy with a line still remembered 160 years later: “Four score and seven years ago…” That man was President Abraham Lincoln. His speech contained only 271 words and its delivery lasted a few short minutes. A main orator spoke earlier that day; former Senator Edward Everett opined for two hours. But Lincoln’s concise remarks were so profound that his speech became famously known as The Gettysburg Address.

Monuments celebrating Lincoln’s leadership are spread throughout Gettysburg. A bronze bust of him is located near the site of his famous speech; another more animated figure of Abe is placed in front of the post office. At the National Park Visitors Center, a pensive Lincoln holds his iconic text with signature stovepipe hat placed at his side. Another whimsical statue has lanky Abe greeting a modern tourist on Gettysburg’s town square.

After 1900, a movement emerged to place monuments on the actual battlefield. Famous soldiers and heroic events were destined to be memorialized for both the north and south. Aging Civil War veterans held several reunions in Gettysburg, bitter war sentiments forgotten as old foes gathered as reunited friends.

One past Union leader remembered in bronze was General Winfield Scott Hancock. His stately equestrian statue commands Cemetery Hill. Wounded during the battle, Hancock survived his injury. According to a popular myth, a rider like Hancock, whose horse stands with one hoof off the ground, symbolizes his type of casualty. If a faux horse has two legs airborne instead, then the rider died, if none, the lucky soldier was uninjured.

After the war, Hancock ran for president in 1880 but lost a close race to fellow Civil War veteran James Garfield. Sadly, Garfield was shot and killed only a few months into his presidency, his life cut short by the same violent act as Abraham Lincoln’s tragic demise.

On the Confederate side, several southern states placed monuments on Gettysburg’s hallowed ground- mostly located on the western side near Seminary Ridge. Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee have memorials here, but the most elegant one is the Louisiana State Monument. Created by famed sculptor Donald De Lue, it is named “Peace and Memory” and was dedicated in 1971.

The statue portrays a wounded New Orleans gunner with the spirit of the confederacy dancing overhead while blowing a trumpet and holding a flaming cannon ball. But the tree that supports the symbolic feature has two trunks, recognizing both northern and southern sacrifices. The Louisiana Monument is an evocative work of art.

In battlefield strategy, the high ground is always an advantageous position, and at Gettysburg that spot is Little Round Top. For modern-day visitors, this famous locale offers a panoramic view of the battlefield, with a vista of the far western mountains.

Standing atop a rocky perch here is a likeness of Gouverneur Warren, a Union General and Chief Engineer for the Army of the Potomac. Warren supposedly stood on this spot during the battle and discovered a Confederate flanking maneuver that threatened this important position. After later resigning his commission following a post-war protest, Warren was eventually buried in civilian clothes, requesting no military honors. Since General Warren faded into obscurity, this monument could also be considered a tribute to the rugged Pennsylvania landscape.

The most impressive monument on the battleground is fittingly the State of Pennsylvania Memorial. This 110-foot-tall granite structure is an architectural wonder, visible from points all over the battlefield. Friezes and statues decorate each side and a 500-pound “Goddess of Victory and Peace” statue, made from melted Civil War cannons, adorns the top. Completed in 1914, the monument commemorates the 34,000 Pennsylvania soldiers who fought at Gettysburg. A spiral staircase leads to the roof so visitors can enjoy an elevated 360-degree view.

As the last of the Civil War veterans faded into mortal history, a new idealistic monument was unveiled in 1938. On July 3rd, 75 years after the battle, President Franklin Roosevelt traveled to Gettysburg to dedicate the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. In attendance were 250,000 people; another 100,000 supposedly never made the ceremony due to gridlocked roads. Originally conceived for the 50th battle anniversary, this monument has relief sculptures of two women and an American eagle. An inscribed hopeful motto on the monument reads: Peace Eternal in a Nation United. Light from its natural gas flame can be seen for 20 miles.

Viewing Gettysburg monuments in modern times, it’s important to remember that these structures often reflect past traditions or selective memory- which includes regional differences, and progressive stages of ethnic diversity and racial civil rights. The memorials also symbolize ideals and opinions of long-ago individuals or organizations who originally built them- not always in sync with contemporary society’s constant march toward a more perfect union.

Despite their connections to fallible humans, the prominent positions these memorials sometimes occupy seemingly suggests they were installed not only to remember historic events but also to celebrate perfect individual character. So, how to judge past historic figures- by today’s standards or the norms of their era? No memorialized historical figure is immune to this difficult question, from Christopher Columbus, to our Founding Fathers, to Civil War Generals.

Monuments sometimes romanticize war, or remind of earlier divisions. But they also hopefully serve as a stern reminder of the brutality that war inflicts on human civilizations, as well as the lessons learned about past injustices suffered by marginalized citizens. As we continuously reflect on our common heritage, the inscription on Gettysburg’s Eternal Peace Memorial is a noble ideal that guides American and world societies into the future.