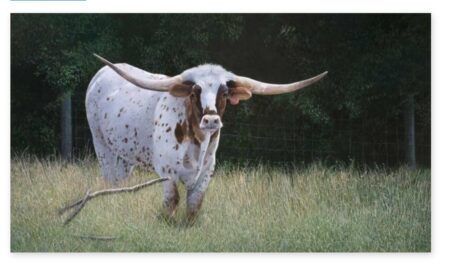

Looking back to tragic historic episodes, and recalling American places that rebounded from disastrous fires, two notable cities immediately come to mind. From October 8-10, 1871, Chicago was stricken with panic after a fire sparked inside a barn, then spread across the city. One legend pins the blame on Mrs. O’Leary’s cow knocking over a lantern. The city was devastated. Thirty-five years later, a major earthquake ruptured gas mains in San Francisco, causing disastrous fires that almost destroyed the bayside city in April 1906. With grit and determination, both cities eventually rebuilt, becoming prominent contemporary centers of commerce and culture.

Franklin County, Pennsylvania offers a third town to a notable list of resilient city survivors: Chambersburg. On July 30, 1864, this community experienced a date with infamy when the entire city was consumed by fire. While the terrible destruction Chambersburg suffered was on a smaller scale than big-city Chicago and San Francisco, it was nevertheless a devastating event that threatened this local town’s survival. An argument could be made that Chambersburg created the first American blueprint for civic rebirth, possibly inspiring those larger cities years later.

Two important distinctions give Chambersburg a unique place in the annals of comeback cities. The first is the origin of their vicious blaze. While the Illinois and California tragedies resulted from an accident and a natural disaster, Chambersburg’s destruction was caused by arson. Also unique to this trio is Chambersburg’s modern interpretation of its traumatic past. This wise community didn’t banish its hellish fire to the ash heap of history. Instead, on a special day every July since 2011, it celebrates that horrific event as a symbol of the town’s resilience and rebirth.

Chambersburg’s dramatic turning point was a milestone in Franklin County history. The path toward peril began when the Confederate Army was defeated at Gettysburg in July 1863. Robert E. Lee’s troops retreated south from Pennsylvania, providing local communities like Chambersburg and Waynesboro, once occupied by those enemy forces, with a sigh of relief. With the war trending toward a Union victory, a Confederate return seemed unlikely. But one year later, the rebels reappeared in northern territory with vengeful hearts.

Under the command of Confederate General Jubal Early, the resurgent southerners held several local towns for ransom. Hagerstown and Frederick paid smaller amounts to the raiders and escaped their fiery torches. But above the Mason-Dixon Line, Chambersburg was threatened with a higher Confederate demand of $500,000. Given scant time to raise that significant amount, Chambersburg weighed limited options for its survival.

Confederates led by General John McCausland showed little patience. Barely waiting for compliance, they set Chambersburg ablaze. As the flames spread, house by house, and block by block, the fires caused an epic disaster. It was a day Chambersburg citizens would certainly beg to forget.

Chambersburg merchant Jacob Hoke penned an eyewitness account of the burning. He described the intensity of the blaze as “a fearful cyclone that originated in the public square, where the converging flames seemed to suddenly give birth and shape to this terrible apparition, moving with a hissing and roaring noise eastward along Market Street. The conflagration at its height was a scene of terror. As building after building was fired, or caught from others, column after column of smoke rose black, straight, and single. Then each of these, like huge serpents, writhed and twisted into fantastic shapes, until all finally commingled and formed one vast and livid column of smoke and flame.”

As the last fires smoldered, Chambersburg’s destruction was witnessed on a massive scale. Two thousand residents were left homeless as 537 buildings were destroyed, causing over $1.5 million in real estate and personal property damage. With a blackened town left in ruins, the future looked bleak. How could Chambersburg’s townspeople rebound from such a despicable act of war? Where would rebuilding resources be found after a careless federal government failed to protect them? Would Chambersburg become a forgotten ghost town?

Fast forward 160 years to modern-day Chambersburg. As a celebratory crowd gathered in its lovely town square on Saturday, July 20th, reenactors emerged in period clothing to begin a unique remembrance. Women in hoop skirts twirled parasols. Soldiers dressed in gray skulked nearby, waiting to make an evil entrance; no blue-coated Yankees in sight. Present-day citizens rode in horse-drawn carriages, driven by costumed Civil War-era tour guides.

The handsome new red-brick Franklin County Courthouse absorbed early evening sunlight, dwarfing the rebuilt old courthouse, preserved next door. Bygone reenactors and a curious crowd came to experience the moment Chambersburg was reborn, by revisiting the day it almost died.

The evening offered a festival atmosphere, with musical performances, historic remarks from speakers, and commemorative Chambersburg 1864 fire T-shirts. As daylight faded, the assembled crowd mingled around the square, anticipating a combative reenactment. A fiery sunset painted the sky red behind the old Courthouse tower as its bell chimed at nine o’clock. When reenactors took their positions, the crowd quieted and craned their necks to see the action unfold.

As the reenactment began, ordinary 1864 citizens strolled into the courthouse square, including Jacob Hoke, portrayed by Charles Rittenhouse. Townswomen and children distributed fruit from wicker baskets, and then socialized in small groups, seemingly oblivious to the upcoming disaster.

Then, Confederates on horseback appeared. General McCausland, played by Samuel Wiser, Jr., dismounted and strode to the courthouse steps. He shouted his infamous Confederate ransom demand. McCausland and Hoke argued, and the frightened townspeople closed ranks. When Chambersburg failed to meet the General’s unfair terms, the courthouse was symbolically set afire.

Other simulated blazes erupted across the square as smoke obscured downtown. An amber glow projected through the windows of an antique building on the diamond’s southeast side, with a realistic fire flickering from its rooftop. But the event’s main focus centered on the old courthouse, which was destroyed by the deliberate fire in 1864. A fog of fake smoke swirled around the building’s white columns, and mixed with the faux sound crackling flames, this gave the reenactment an eerie pall. The realistic special effects (provided by Eslinger Lighting) gave modern-day viewers a sense of the chaos and calamity that Chambersburg residents faced on that awful July day.

The reenactment played itself out as the smoke and flames eventually dissipated. The dastardly Confederates fled on horses. Then, the townspeople in period clothing reunited on the courthouse steps, showing an instant spirit of community pride. They sang patriotic songs and unfurled a weathered flag. The classic architectural form of the courthouse came back into clear view. A tense mood lifted. The crowd cheered; Chambersburg would survive.

Back in 1864, shortly after the burning, a local newspaper editorial said: “Dark as is the hour, but let us not forget that it has the promise of future prosperity in our town. Let us therefore make common cause to restore Chambersburg; to help the needy and give prompt and permanent aid to make the town better than before.” Another editor remarked: “The glorious spectacle of a prosperous, re-united, and happy people will soon again be presented in this land, so cursed by the rebellion, tyranny, and war. God speed the dawn of a brighter day.”

Those optimistic sentiments were realized in future months and years. Chambersburg not only rebuilt its buildings, reclaiming its pre-war status, but moved forward with collective force to achieve post-war respect and success.

Only a month after the burning, the town’s leaders formulated plans to rebuild their community. They started by planting shade trees and widening Main Street. On July 20, 1878, 15,000 people gathered to dedicate the Memorial Fountain, a 26-foot-tall cast iron and bronze water feature that honored the county’s veterans. This symbolic landmark still stands today as the square’s distinctive centerpiece. By the turn of the century, Chambersburg had 9000 residents, almost twice the size of its 1864 population.

During the 1900s, Chambersburg enjoyed a vibrant Progressive Era. A multitude of business successes, including prominent grain, lumber, and paper mills, and manufacturers of agricultural equipment, helped the town prosper. The Cumberland Valley Railroad thrived, as did the town’s official role as the seat of Franklin County government. Today, Chambersburg boasts a population of 22,000 and is the crown jewel of a PA county that possesses abundant natural resources and a fascinating tapestry of local history.

The Franklin County Visitor Bureau (explorefranklincountypa.com), sponsors the annual Burning of Chambersburg living history reenactment. This unique event continues to offer unique perspectives on the tenacity, spirit, and willpower of Chambersburg’s past citizens. They overcame great odds to survive a tumultuous episode, forever searing their story into an inspiring chapter of an American town’s resilience and rebirth.