The Liberty Bell in an American icon. Throughout its 272-year existence, the bell has chimed a resounding tone of patriotic sentiment, survived guarded secrecy, and spurred enduring myths. The Liberty Bell symbolizes America’s success story, but its history contains other fascinating aspects, including notable failures. On January 6, 1902, a chapter in this famous bell’s story played out as it passed through the Cumberland Valley.

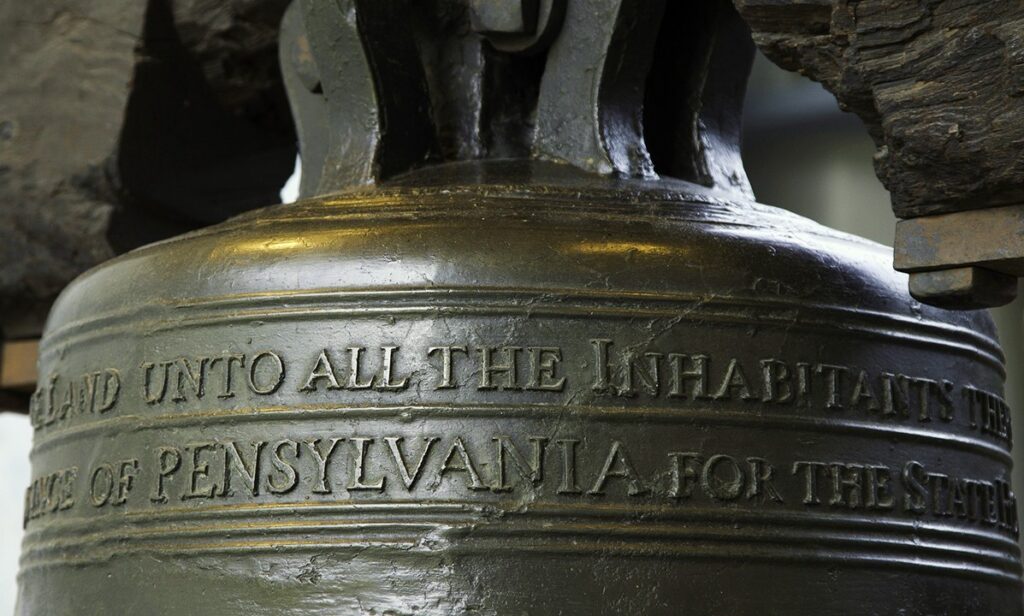

Originally called the State House bell, the bell was commissioned by Pennsylvania’s Assembly in 1751. Speaker Isaac Norris ordered it from London’s Whitechapel Foundry. Norris also picked the bell’s inscription: “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All The Land Unto All the Inhabitants Thereof.”

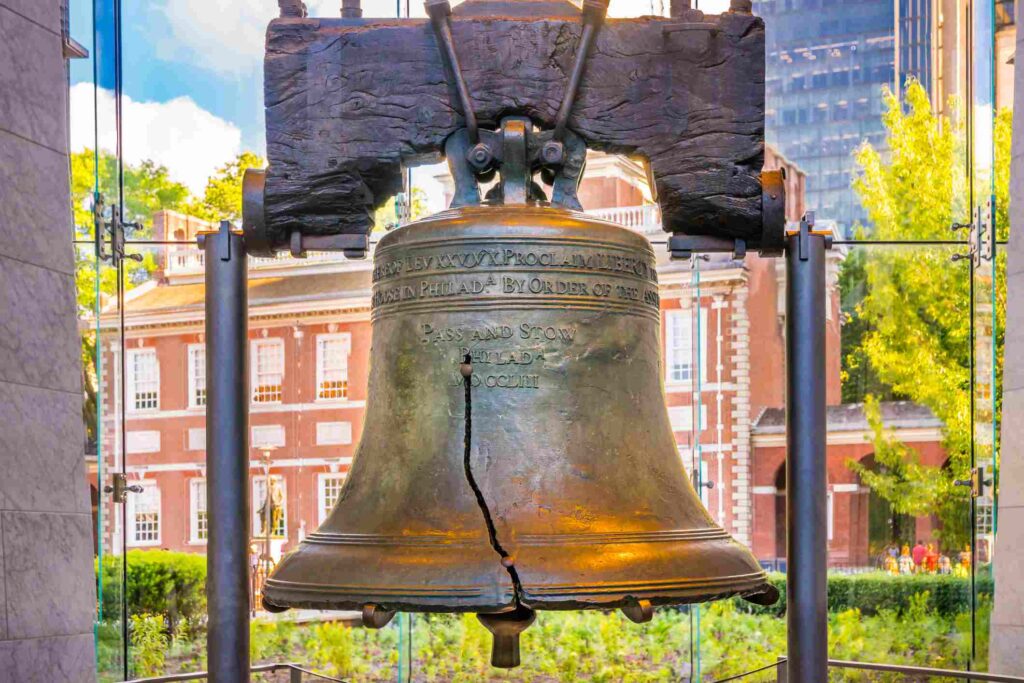

The bell was delivered to Philadelphia in August, 1752. Its original purpose: summoning lawmakers to the State House building (now known as Independence Hall) and calling local citizens for latest news. From the beginning, the bell had problems: when initially tested, it supposedly cracked. Norris tried returning the bell, but its delivery ship already sailed toward London. Two Pennsylvania metalworkers named John Pass and John Stow offered to fix the faulty bell. The pair chipped it into pieces, melted down the original bell, and recast it.

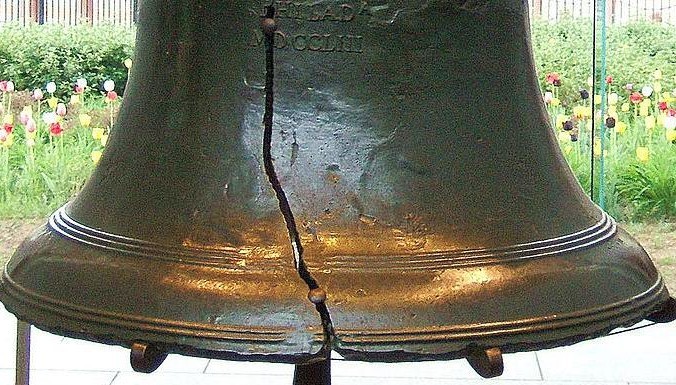

In April 1753, the second bell was unveiled. Unfortunately, the bell’s ring-tone pleased no one. So, Pass and Stow returned to work, recasting a second time. Finally, the third bell proved satisfactory, and when completed it weighed 2080 pounds, and at its lip measured a twelve-foot circumference and stood about four-feet tall. The brass bell was 70% copper, 25% tin, and had trace elements of gold, silver, and zinc in its construction.

Two decades later, despite a popular myth, no evidence exists that the future Liberty Bell rang in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed.

During the Revolutionary War, the State House bell took its first road trip. Pennsylvania authorities worried invading British armies might melt down the metal bell for munitions, so in 1777 it was secretly moved to Allentown, Pennsylvania. At Zion Reformed Church, the bell was concealed in the basement until danger passed. The bell returned home a year later. For the next seven decades, it performed its duty, ringing regular announcements, and tolling to mourn notable deaths of American heroes Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson.

Sometime around 1846, a zigzag crack formed on the hard-working bell. The cause and exact date of this fracture are disputed among historians. Afterward, workmen attempted repairing the bell by actually widening the crack, to prevent further spread. This method, called “stop drilling” failed, and the bell was forever silenced. Another State House bell was commissioned, and the newly known Old State House Bell was first put into storage, and then later used only for display.

But as the failed bell faded into retirement, a remarkable reputation developed. An abolitionist newspaper noted the bell’s inscription, which proclaimed liberty to all American inhabitants. In an 1837 article, the bell was called “Liberty Bell” for the first time, not in celebration, but in protest of slavery. In time, this example would be followed by 20th century Suffragettes and others seeking Civil Rights. The Liberty Bell became a symbol of not only what America was, but what it could become.

As Americans celebrated their centennial in 1876, the Liberty Bell served as a symbolic centerpiece. The United States was reunited after a devastating Civil War, and the newly famous (but silent) bell was seen as a fitting metaphor to the country it served: damaged, but still intact.

With its growing symbolism, distant Americans wanted to see the bell firsthand- but trips during that era measured in weeks not days. If Americans lived far from Liberty Bell’s Philadelphia home, maybe the relic would visit them.

In 1885, that wish came true. Despite concerns about its fragility from its Philadelphia owners, the Liberty Bell was put on a train, bound for New Orlean’s World’s Industrial and Cotton Exposition. At railroad depots stops along the way, crowds flocked to see the bell. That same year, another future American icon arrived (unassembled in gigantic pieces) in New York City: The Statue of Liberty.

Another train excursion took Liberty Bell to an 1893 Chicago fair, then an Atlanta exposition in 1895. Each time, the frail bell survived rail travel and worshipping throngs, and came home safely.

By 1900, the bell’s keepers grew increasingly nervous about visitation requests from around the country. Pennsylvania Governor Samuel Pennypacker said he didn’t want the Liberty Bell associated with “fat pigs and fancy furniture” at far-flung fairs. A metallurgist named Alexander Outerbridge Jr. served like the bell’s personal physician. He said his patient suffered from a “disease of metals” and predicted it faced certain destruction if ever moved again.

But in 1902, the next Liberty Bell excursion was scheduled, taking it to Charleston, for the South Carolina Interstate and West Indies Exposition. Despite objections from Philadelphia naysayers, the trip went forward. On January 4th, the bell left Philadelphia, protected by four muscular policemen and accompanied by onboard dignitaries.

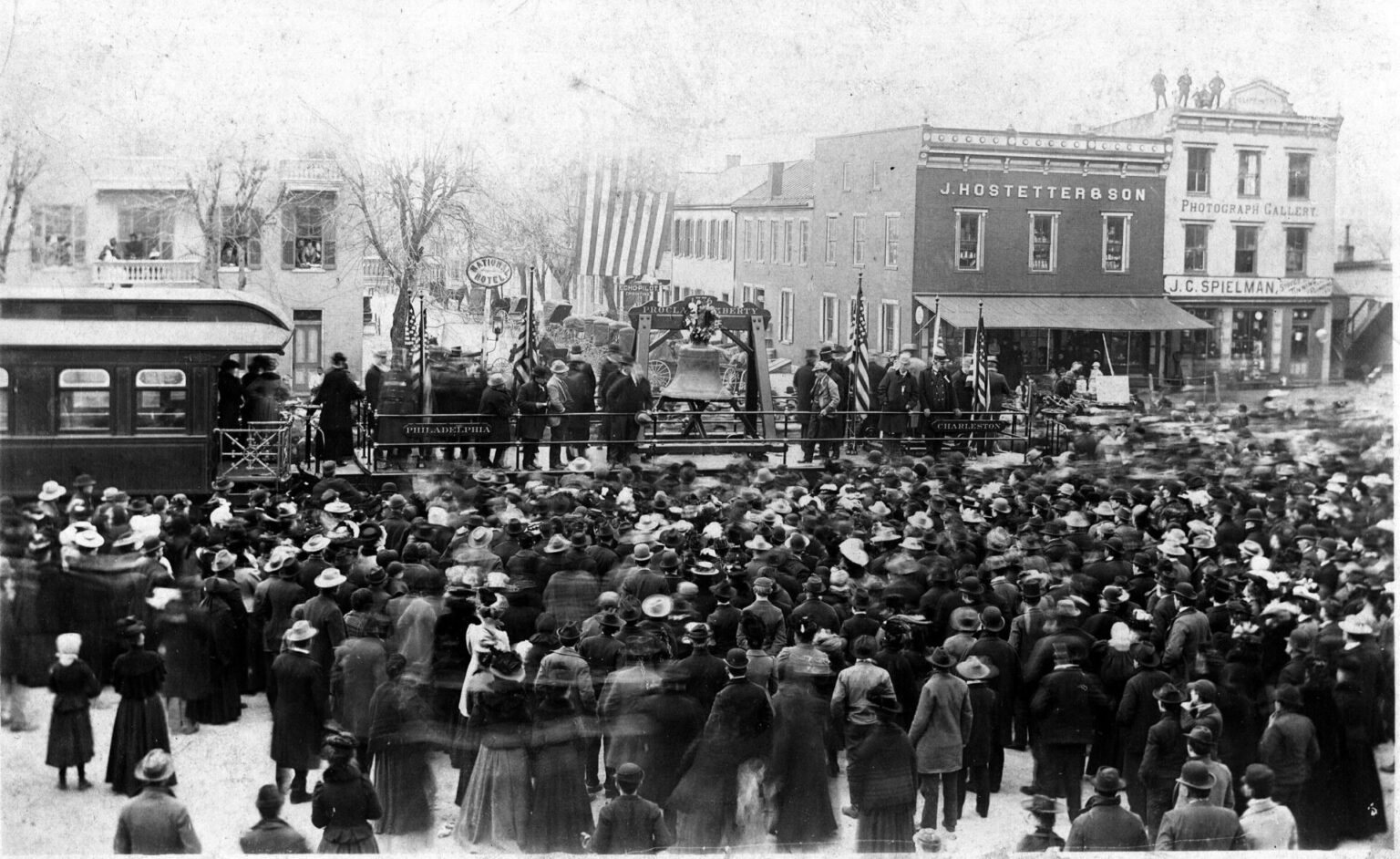

Once in Harrisburg, railroad cars were switched to the Cumberland Valley Railroad and headed southwest. Later that day at 2:05 pm, the train made a scheduled stop in Chambersburg. An estimated 4,000 people gawked at the bell, jostling to see the famous brass icon. Chambersburg’s Mayor welcomed Philadelphia Mayor Ashbridge. Keeping a strict schedule, the seven-car train left 25 minutes later.

The next stop was Greencastle. Another joyful scene developed in the town’s square as residents gathered to welcome the Liberty Bell’s train. Many citizens peered from upstairs windows and others watched on rooftops.

Then, the “Liberty Bell Special” trekked toward Hagerstown. The city was abuzz as 8,000 eagerly awaited the train. Hagerstown’s City Band warmed up the crowd with patriotic songs. When the metallic guest of honor arrived, citizens waved their hats and cheered. The Hagerstown Mayor and Town Council greeted onboard guests and were given badges with pictures of Liberty Bell.

Several thousand school children were also present, and books containing Liberty Bell’s history were tossed to them. Many youngsters were lifted up to the gondola by parents so they could touch or sit near the famous bell. Smiles prevailed as the train departed another thrilled community on its journey south.

An article published inside Pennsylvania Grange News in 1936 described what happened next. Liberty Bell’s train chugged into Virginia on the evening of January 6th. After a lavish dining car meal, men played cards and smoked cigars. A thick fog developed after midnight. Near Luray, Virginia, a second train had pulled over to let the Charleston-bound locomotive pass with its famous cargo. Due to poor visibility, it hadn’t pulled entirely off the siding, and was struck by Liberty Bell’s train.

According to the article’s author, the train’s engine crew was killed and two forward baggage cars caught fire. The rear car holding the Liberty Bell was uncoupled and moved away from the burning wreckage. Thanks to brave men onboard, the Liberty Bell was saved. But it seemed the worst fears of Philadelphians had materialized. When the bell returned from Charleston in June 1902, it seemed likely it would never leave Pennsylvania again.

But In 1903, the Liberty Bell traveled to Boston, and then St. Louis the following year. In 1915, it embarked on its most ambitious over-rail journey- a 10,000 mile roundtrip to San Francisco. Custom springs were placed under the bell’s platform to cushion the fragile relic. An estimated 10 million people saw the bell during numerous stops to and from San Francisco.

Why had the cracked bell’s handlers allowed those risky jaunts? One possible explanation about those post-1902 trips- that 1936 magazine article was inaccurate. Historians later noted a train crash did occur in Virginia, but in June that year, not January. The accident happened before picking up Liberty Bell for the return trip, so the bell was not onboard. Since many years had passed, the 1936 erroneous story was accepted as fact, and later perpetuated in other writings until the mid-1990s.

After 1915, the Liberty Bell never left Philadelphia. It made five public appearances- three times to celebrate local festivities, and twice when moving to a new home. An updated pavilion housed it in the 1976 bicentennial year. Later in 2003, a modern structure called Liberty Bell Center was dedicated to showcase the famed object. Today, over a million visitors make a pilgrimage each year. Touching the fragile bell, once common on its whirlwind touring trips, is now wisely forbidden.

The Liberty Bell is firmly established as an American symbol, seen on postage stamps and other prominent commercial products. It survived tumultuous times as a tolling bell and a priceless yet flawed artifact. It created a slice of local history during its American journey, but now likely will stay home to welcome its adoring fans.