In the early days of Pennsylvania’s statehood, whiskey served as more than adult refreshment. The drink’s cultural and economic impact was legendary. On some occasions whiskey was even used as legal tender, a currency of liquid gold. In time, Pennsylvania became the new nation’s largest producer of that alcoholic spirit, known for a popular variety: rye whiskey. When distillers later faced threats to their traditions and livelihoods, a harsh reaction was inevitable. Whiskey was worthy of a fight.

The United States levied a whiskey tax in 1791. A heavier burden of that tariff fell on smaller producers and after several years with the government’s unwelcome hand in their coffers, distillers in western Pennsylvania were furious. Five hundred armed men attacked a tax collector’s home. Many others refused to pay taxes due. President George Washington took to the saddle and commanded a force of 13,000 soldiers to quash the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion.

After the Civil War, tempers cooled and Pennsylvania’s distilling industry gathered peaceful momentum. Franklin County farmers owned an abundance of whiskey-making’s two most important ingredients: surplus grain and pure water from crystal-clear streams. In Rouzerville and Midvale, several springs were tapped, those waters said to contain sweet-tasting minerals.

In 1888, Joseph C. Clugston, an enterprising man with experience as a merchant, miller, and newspaper owner, leased Shockey’s Distillery. The enterprise harvested water from a local source called Indian Spring.

Clugston put a more ambitious plan in motion by 1891, opening a retail package store in Waynesboro and buying a nearby sawmill and warehouse on Cleveland Avenue as a base for his new operation. Ads for his store said: “If you want Pure Rye Double Copper Distilled Hop Yeast Whiskey (pure and unadulterated), call at my new liquor store on West Main Street.” Soon after, Clugston established other retail outlets in Hagerstown, Baltimore, and Norfolk, Virginia.

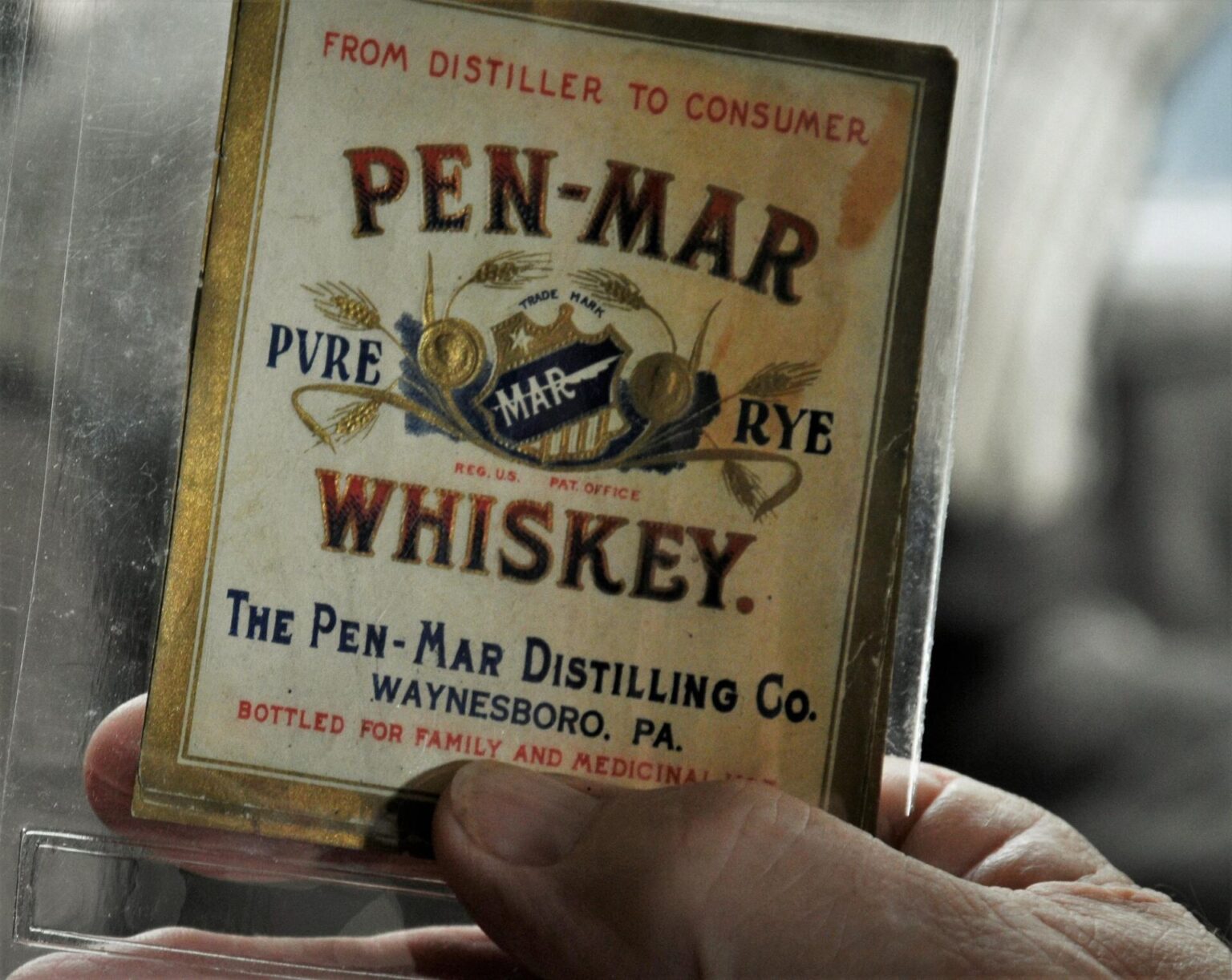

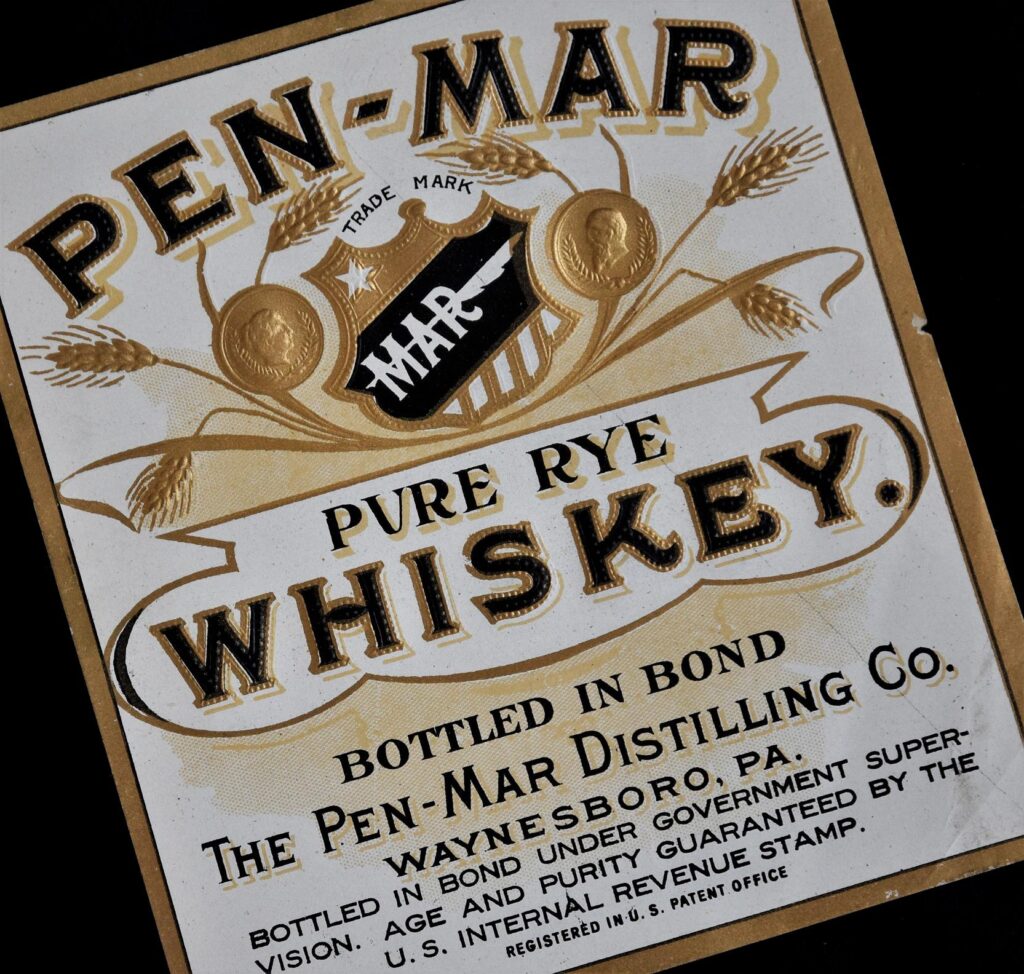

He called his new brand Pen-Mar Pure Rye Whiskey. Clugston may have capitalized on the popularity of nearby Pen Mar Park with that name, the scenic mountain attraction opened a few years earlier. Several rustic inns surrounded the park. The spirits and hospitality industries were closely linked and Clugston would later buy Waynesboro’s Washington Hotel in 1896.

Clugston customized his new distilling property for optimum efficiency. He installed a new cleaning apparatus that scoured grain to remove impurities. Clugston owned a cooper shop, producing custom whiskey barrels. A large steam-powered racking system kept his warehouse’s internal temperature at a toasty 90 degrees, allowing the product to fully mature in only two years. In 1897, he was the first southern Pennsylvania distiller to bottle and distribute bonded spirits. After years of hard work, Pen-Mar Whiskey became the largest distillery in Franklin County.

When the 20th century began, Clugston suffered a sad reversal of fortune. First, he was attacked by two employees, who were arrested and punished, but the episode left Clugston shaken. Shortly after the criminal trial, he transferred company ownership to his children. A short time later, Clugston suffered another setback when his gangrenous left foot was amputated. A chronic illness associated with that incident led to further decline. Joseph C. Clugston died in 1905.

Under the leadership of Clugston’s sons, Pen Mar Distilling grew and prospered. In 1907, they achieved the greatest production output in company history. Their rye whiskey had received many accolades for its smooth taste and consistent quality. The future seemed bright. But a storm brewed on the horizon: the long-simmering temperance movement.

The push to limit alcohol consumption began many years earlier, first with pleas for moderation during the 1830’s. Teetotalism was later advocated by many religious sects. The Anti-Saloon League formed in 1893 and by 1900 an estimated one-tenth of Americans signed a pledge to give up alcohol.

In the 1910’s, a Constitutional movement gained unstoppable momentum. The 18th Amendment was ratified in January, 1919. 46 of 48 states passed the Amendment (Rhode Island and Connecticut the only two ‘wet’ holdouts). Perhaps as a last defiant nod to their 1794 rebellion, Pennsylvania was the 45th (and next to last) state to ratify the 18th amendment. The new law banned the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcoholic beverages. In January, 1920, enforcement of Prohibition began.

With the stroke of a legislative pen, distilleries big and small were rendered illegal. An entire thriving industry vanished almost overnight. One loophole in the new law allowed alcohol sales for ‘medicinal purposes’, but that kept only a few well-connected businesses afloat. Despite a quaint medical reference on their colorful labels, the Pen Mar Distilling Company was liquidated.

Thirteen years passed before Congress reversed Prohibition. Widespread bootlegging and organized crime had made the statute unenforceable. The 21st Amendment re-established American industry’s right to distill and sell alcohol. Whiskey was back in business.

But after legal production began again in 1933, rye whiskey fell out of favor and bourbon (made with corn) became the beverage of choice. Kentucky filled that market niche. Most small distilleries never returned, leaving production to major manufacturers. The legacy of Pennsylvania’s local whiskey distillers seemed destined for obscurity, with Pen-Mar Distilling another forgotten relic from a bygone era. But Wayne Bartholow chose to remember and celebrate that rich distilling heritage.

Bartholow, 76, is a Waynesboro native retired after a successful banking career. He is also a tuba player in the Wayne Band, a group that will celebrate its 125th anniversary in 2024. Wayne is an avid collector. His paternal grandfather, Fred, worked in the hospitality business, first bartending at the Anthony Wayne Hotel, then the Central Hotel (later known as the White Swan), and finally employed at Werner Hotel, all located in downtown Waynesboro. Fred saved a few keepsakes from his shifts, including bottles of Pen-Mar Whiskey. After he died, some of his souvenirs passed into grandson Wayne’s care.

Wayne was curious about Pen-Mar’s brand and started researching. His fascination grew and over many years he gathered a treasure of distilling artifacts. Wayne owns obvious relics- whiskey bottles and shot glasses, but also boasts a liquor license issued to his granddad in February, 1919 (then surrendered for Prohibition in December that same year), an antique clock with a Pen-Mar logo, and various nostalgic ads promoting the company.

After pulling out an unopened Pen-Mar whiskey bottle at least a century old, Wayne shook his head no when asked if it will ever be opened. Despite his fondness for the Pen-Mar story, and the golden luster of the liquid trapped inside, the taste of that ancient whiskey will remain a mystery.

Wayne has given Pen-Mar Whiskey presentations to local groups and led field trips to old distillery sites. In 2010, Wayne went a step further. He secured official corporate naming rights to “Pen-Mar Rye Whiskey”, preserving that brand name for a possible future distiller. Perhaps one day a new version of Pen-Mar rye will return to Franklin County liquor cabinets.

Wayne Bartholow is not alone in his remembrance of Pennsylvania’s whiskey legacy. More than 50 new distilleries have sprung up all over the state, offering unique spirits to a growing legion of fans. Pennsylvania appears poised to reclaim its distilling glory days. Several websites offer suggestions for further exploration (padistillersguild.com and whiskeyrebelliontrail.com). Franklin County’s only current operating distillery is Cold Spring Hollow in Mercersburg (coldspringhollowdistillery.com, 717-498-0770). They create small-batch handcrafted whiskeys, bourbons, and other spirits.